Ancient Tales and Folk-lore of Japan, by Richard Gordon Smith, [1918], at sacred-texts.com

Click to enlarge

12. The Procession of Ghosts

IX

'THE PROCESSION OF GHOSTS' 1

SOME four or five hundred years ago there was an old temple not far from Fushimi, near Kyoto. It was called the Shozenji temple, and had been deserted for many years, priests fearing to live there, on account of the ghosts which were said to haunt it. Still, no one had ever seen the ghosts. No doubt the story came into the people's minds from the fact that the whole of the priests had been killed by a large band of robbers many years beyond the memory of men—for the sake of loot, of course.

So great a horror did this strike into the minds of all, that the temple was allowed to rot and run to ruin.

One year a priest, a pilgrim and a stranger, passed by the temple, and, not knowing its history, went in and sought refuge from the weather, instead of continuing his journey to Fushimi. Having cold rice in his wallet, he felt that he could not do better than pass the night there; for, though the weather might be cold, he would at all events save drenching the only clothes which he had, and be well off in the morning.

The good man took up his quarters in one of the smaller rooms, which was in less bad repair than the rest of the place; and, after eating his meal, said his prayers and lay down to sleep, while the rain fell in torrents on the roof and the wind howled through the creaky buildings. Try as he might, the priest could not sleep, for the cold draughts chilled him to the marrow. Somewhere about midnight the old man heard weird and unnatural noises. They seemed to proceed from the main building.

Prompted by curiosity, he arose; and when he got to the main building he found Hiyakki Yakô (meaning a procession of one hundred ghosts)—a term, I believe, which had been generally applied to a company of ghosts. The ghosts fought, wrestled, danced, and made merry. Though greatly alarmed at first, our priest became interested. After a few moments, however, more awful spirit-like ghosts came on the scene. The priest ran back to the small room, into which he barred himself; and he spent the rest of the night saying masses for the souls of the dead.

At daybreak, though the weather continued wet, the priest departed. He told the villagers what he had seen,

and they spread the news so widely that within three or four days the temple was known as the worst-haunted temple in the neighbourhood.

It was at this time that the celebrated painter Tosa Mitsunobu heard of it. Having ever been anxious to paint a picture of Hiyakki Yakô, he thought that a sight of the ghosts in Shozenji temple might give him the necessary material: so off to Fushimi and Shozenji he started.

Mitsunobu went straight to the temple at dusk, and sat up all night in no very happy state of mind; but he saw no ghosts, and heard no noise.

Next morning he opened all the windows and doors and flooded the main temple with light. No sooner had he done this than he found the walls of the place covered, as it were, with the figures or drawings of ghosts of indescribable complexity. There were far more than two hundred, and all different.

Could he but remember them! That was what Tosa Mitsunobu thought. Drawing his notebook and brush from his pocket, he proceeded to take them down minutely. This occupied the best part of the day.

During his examination of the outlines of the various ghosts and goblins which he had drawn, Mitsunobu saw that the fantastic shapes had come from cracks in the damp deserted walls; these cracks were filled with fungi and mildew, which in their turn produced the toning, colouring, and eventually the figures from which he compiled his celebrated picture Hiyakki Yakô. 1 Grateful

was he to the imaginative priest whose stories had led him to the place. Without him never would the picture have been drawn; never could the horrible aspects of so many ghosts and goblins have entered the mind of one man, no matter how imaginative.

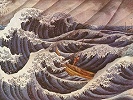

My painter's illustration gives a few, copied from a first-hand copy of Mitsunobu's.

Footnotes

61:1 Somewhere between the years 1400 and 1550 there lived a family of celebrated painters covering three generations, and consequently difficult to be accurate about. There were Tosa Mitsunobu, Kano Mitsunobu, and Hasegawa Mitsunobu; sometimes Tosa Mitsunobu signed his pictures as Fujiwara Mitsunobu. When to this I add that there were other celebrated painters—Kano Masanobu, Kano Motonobu, besides their families, imitators, and name forgers—you will realise the difficulties into which one may fall in fixing on names and dates; but, as usual, I have been placed safely on high ground by a kind friend, H.E. Mr. Hattori, the Governor, whose knowledge of Art is great. Undoubtedly it was Tosa Mitsunobu who painted the picture known as the Hiyakki Yakô, or as 'The One Hundred Ghosts' Procession, which is celebrated, and has served as a map of instruction in the drawing of hobgoblins and ghosts, 'spooks,' 'eries,' or whatever you may choose to call them. As far as I can judge, the picture was painted about the end of the first half of the fifteenth century.

63:1 It is well known that certain fungi and mildews produce phosphorescent light amid certain circumstances. No doubt the priest saw the cracks in the wall amid these p. 64 circumstances, and the noise he heard was made by rats. I once read a story about a haunted country-house in England, the ghost in which was eventually found to be a luminous fungus.