"E nos Lases iuvate,

Neve luerve Marmar sins incurrere in pleoris.

Satur furere Mars limen sali, sta berber.

Semunis alternei advocavit conctos

E nos Marmo iuvato.

Triumpe. Triumpe."

Song of the Arval Brothers

BY the Latin words Lar and Lares we generally understand domestic family spirits, on which subject MÜLLER (die Etrusker) gives much information and conjecture. He writes: "That the Lares belong to the Tuscan mythology is shown by the name, for as Larth and Laris were common surnames, they must have originated in an Ehrennahme (some common name of honour). But both among Tuscans and Romans it was a very comprehensive name. . . . There were

BY the Latin words Lar and Lares we generally understand domestic family spirits, on which subject MÜLLER (die Etrusker) gives much information and conjecture. He writes: "That the Lares belong to the Tuscan mythology is shown by the name, for as Larth and Laris were common surnames, they must have originated in an Ehrennahme (some common name of honour). But both among Tuscans and Romans it was a very comprehensive name. . . . There were

Lares coelopolentes, permarini, viales, vicorum, compitales, civitatum, rurales, grundules, and finally the domestici and familiares, the comprehension of which

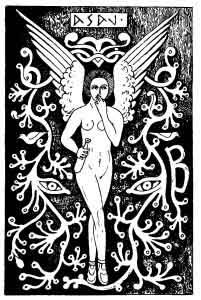

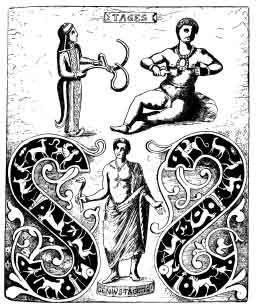

LASA, OR GUARDIAN SPIRIT

in the course of time has become obscure, owing to confusion with the others. The rural Lares, on the other hand, are those which in the very ancient song of the Arval brothers are called on as E nos Lases iuvate."

"Lases was certainly in Rome the oldest form of the word " (Note p. 93).

"Now it is very remarkable at first sight that under these extremely varied deities there are human souls." This is confirmed by MÜLLER with a mass of proofs. He then adds:--

"The Lares familiares must necessarily be included among these, as they were generally nothing else than souls of ancestors become gods, many of the ancients (APULEIUS, MARTIAN, and VARRO) having declared that genius and lar, referring especially to domestic lares, were one and the same."

Our author declares that the Lasa were generally female spirits occupied it, adorning men and women, as depicted on vases, and that, "so far as Etruscan is concerned, it is doubtful whether Lasa and the Lares are connected."

Conversing one day with my best authority on Tuscan folk-lore, I asked if she knew such a word as Lar, Lares, or Lare? "No, she had never heard it." "Did anything with a similar name haunt churchyards?" "No; but," reflecting a minute, "there are the Lassi or Lassie." "And what are they?" The answer was as follows:--

"Lassi are spirits which are heard or seen in a house when one of the family dies. They are the ghosts of the ancestors of the family, who come at such a time."

This was conclusive, and I have no doubt that these Lassi or Lasie are the Lasa referred to in the song of the Arval brothers. Of course this is not absolutely proved, but when we consider that Tinia, Fufluns, Feronia, and Mania all exist with most of their ancient characteristics, it must be admitted that we have here an extremely strong probability. The Lasa were in the very oldest Latin in existence ghosts of ancestors, or domestic familiar spirits, and so are the Lassi. And MÜLLER gives no proof whatever that the Lasa, or "winged spirits on the vases, with a frontal band or cap and earrings, naked or in a short chiton with armlets, half boots or shoes," and holding a great variety of objects in their hands, were not Lares deified. It seems to me to be most natural that the spirits of the ancestors, revived in youth and beauty, should be the first to wait on and aid the descendant risen to paradise. MÜLLER himself says elsewhere, "In the Lar the Genius always comes to light." What are these Lasa, if not the geniuses of the departed? Unfortunately, MÜLLER, though gifted with perfectly German industry, and not deficient in sagacity, had not a gleam of intelligence as regarded the folk-lore of a race, or the immense value of minor matters. To write in an admirable and clear style, en grand critique, over the great events or subjects of a race is certainly very fine, but it is to be hoped that a time is coming when we shall have seen the last of these Mr. Dombeys of History, with their prize works

crowned by Academies, in which there is not a gleam of intuition, nor a nuance of colour, and as little real knowledge of life.

There is a story of the Lasi or Lasii, also an invocation to them. I would say that, as regards the songs or metrical passages in all such accounts, I have not been able, with all care, to give them in the original or best form. In most cases my informant translated them from the original Romagnola dialect into Italian, and they were often manifestly imperfect or partly supplied. The tale is as follows:--

"There was once a great lord who was very rich, and he had a son who was a great prodigal--che sciupeva tutto il danaro. His father said to him, 'My son, I cannot live long, therefore I beg you to always behave well. Do not go on gambling, as you are wont to do, and waste all your patrimony. While I live I can take care of you, but I fear for you after my death.' After a little time the father died. And in a few days the son brought all to an end. Nothing remained but the palace, which he sold. But those who occupied it could not dwell there in peace, because at midnight there was heard a great clanking of chains and all the bells ringing. And they saw black figures like smoke passing about, and flames of fire. And they heard a voice saying:--

"Sono il Lasio,

In compagnia

Di tanti Lasii,

E non avrete mai

Bene, fino che

Non prenderete

Questo palazzo

A mio figlio.' 1

("'I am the Lasio,

And there are with me

Many more Lasii.

No good shall come to you

Till you restore

This place to my son!')

"So they gave back the palace to the heir. But he too was greatly terrified with the apparitions, and

there came to him a voice which said:--

"'Sono il Lasio

Di tutti Lasii,

Son' tuo padre,

Che vengo adesso

In tuo soccorso

Purche tu m'ubbedisca,

Smetti il giuoco,

Altrimenti non avro

Mai pace--e tu

Ti troverai ancora

In miseria estrema;

Ma se tu m'ubbedisca,

Io vivro in pace,

E sarai tanto ricco

Da non finire

Il tuo patrimonio;

Anche divertendo te

E faccendo molto bene,

Ma prometté mi

Di non piu giuocare.'

("'I am the Lasio

Of all the Lasii.

I am thy father

Come to thy succour;

If thou'lt obey me,

Cease gaming for ever,

Or thou shalt never

Know peace . . . and thou

Wilt again find thyself

Stink deep in misery;

But if thou obey'st me,

I shall have peace again,

And thou shalt be wealthy

Far beyond measure,

Living in pleasure;

Only this promise me,

Never to play again.')

"Then the son answered:--

"'Padre perdonatemi!

Non giuochero pin.'

("'Father, forgive me;

I will ne'er play again.')

"Then the father replied:--

"'Rompi quante trave

Che son' nel palazzo

E piene di danaro,

Le trovarei,

Cosi starei benme,

Ed io staro in pace,

Nelle require

E mettermi. Amen!'"

("'Break down the beams

Which are in the palace

They are full of money,

As you will find.

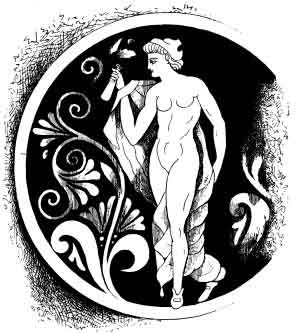

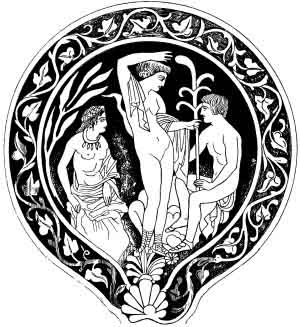

FAUN AND FEMALE LASA OR FAIRY

Then I shall be quiet

In the rest of the dead.

There I go. Amen!"')

It was explained to me that by the beams meant breaking away the ceiling. Two things strike me in this strange semi-poem. One is that the story is very much like that of the Heir of Lynne in PERCY'S Relics. Secondly, that it is altogether more like an Icelandic narrative than anything Italian. It is grim, strong, and very simple--one may say almost archaic.

There is also an invocation of witchcraft to these spirits of ancestors which is not less curious:--

"Lasii, Lasii, Lasii!

Che tante buoni siete

D'una grazia io ne ho

Gran bisogno;

E da vuoi spiriti

Spiriti e Lasi,

In mezzo a uno cantina,

Mi vengo inginnochiare

A vuoi altri

Mi vengo a raccomandare

Che questa grazia.

Mi vorrete fare!

Lasii, Lasii, Lasii!

A vuoi vi presento,

Con tre candele,

Candele accese,

Tre carte, l'asso di picche,

Quello di fiori,

E quello di quadri,

Le buttero per l'aria,

Che vuoi certo mi vedete

Per cio le butto

In vostra presenza

Nell punto della mezza notte,

Queste carte

Per l'aria buttero,

Se la grazia mi farete,

L'asso di fiori scoperto,

Trovare mi farete,

Se scoperto l'asso di pique,

Mi fate trovare,

E segno che la grazia

Non me volete fare;

Se mi farete trovare

Quello di quadri

Segno e che

La grazia mi fate."

("Lasii, Lasii, Lasii!

Ye who are gracious

There is a favour

Which I need greatly,

And of ye spirits,

Spirits and Lasii,

Here in a cellar

Now I am kneeling,

And I commend myself

Unto your graces,

That ye will grant me

This special favour!

Lasii, Lasii, Lasii!

Here I present myself,

Bearing three candles,

Three candles lighted,

Three cards--the ace of spades,

And that of clubs,

And that of diamonds.

I fling them in the air

That you may see them

Plainly before you,

Here just at midnight

In air I throw them;

If you grant me a favour,

Cause me to find

The ace of clubs plainly.

If 'tis the ace of spades

'Tis a sign that you will not

Grant me the favour;

But if you make me find

The ace of diamonds,

Then 'tis a sign

That my wish will he granted.")

"But," added the fortune-teller, in a prosaic voice, "it will not be until after a long time."

Games of chance and lotteries are such a serious element in Italian life that no one need be astonished at an invocation like this being addressed to the Lares. Perhaps the Romans did the same for luck at alea, or dice. I would that I had by me my copy of PASCHASIUS JUSTUS' De Alea. I might find it in that!

It may be remarked that in this account the Lasii appear as benevolent spirits, devoted to a family. Since recording this Tuscan story of the Lasio who gave the treasure, I have met with the following in the Romische Mythologie of L. PRELLER:--

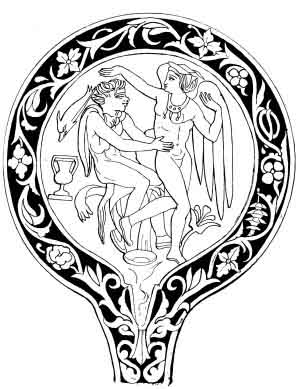

TINIA AND LASA

"The lar familiaris is the Schutzgeist--guardian spirit of the family. Next to the Lar familiaris, who is simply called the lar or lar pater (the father lasio), there are many lares familiares. . . . It happens, perhaps, that the grandfather confided a treasure to him which he secretly hid . . . and he gives this to the only daughter of the house, a good girl who has always given him daily offerings such as incense or wine or garlands."

This is briefly the same story as that which I have related. The Lar or Lasio has a treasure in reserve which he gives to the heir. It was comfortable to think that there was in the house an attached family spirit who might do one a good turn, and therefore the belief lasted long among all rural people.

The young man Peppino, who went about much, at home and in the marketplaces, to collect evidence of knowledge of the spirits by me recorded, found that the Lasii were known, but gives the name as Ilasii. This is evidently only an addition of the plural article i (the) to Lasii.

Some time after I had written the foregoing relative to the Lasii, I heard the following, which I made the narrator repeat, and took down accurately:--

"When I was about twelve years of age something happened to me which I thought at the time was funny or queer (mi trovai à un caso buffo--cosi io to chiamai), but I have since regarded it in a very different light. Once I went with some relations into the country. One day I was in a dark forest, and wandered about picking leaves and wood-flowers, and at last found myself in a very lonely place by a stream. I had a habit of talking aloud to myself, and I said, 'Oh, I would like to bathe there'--the weather was very hot--when all at once there stood before me an old woman, who said: 'Dear child, if thou wouldst like to bathe, undress without fear, I will protect thee.' There was something about her which pleased me greatly, a care and kindness and sweetness which I cannot describe. And when I had bathed and dressed myself she said: 'Bimba, thou hast had many troubles, and many more are before thee, but be not afraid (non ti sgomentare), for in thy old age thou wilt have good fortune,' and so she disappeared, and I never saw her again--and I still await the good fortune which has not as yet come to me.

I believe this was indeed a lasia, a spirit of some ancestor long dead, who wishes me well.

What was best in this story I cannot relate, and that was the earnestness with which it was told, and the manner in which the narrator repeated the details, and the deep faith with which she expressed the conviction that this was really a lasia. Truly they are a strange race, these Etruscan mountaineers -their young folk see visions and their old men dream dreams.

Pictures of Lases abound on Etruscan vases. They arc represented as beautiful spirits, young, and more frequently feminine than male. They are, I believe almost always, winged, and generally bear a bottle or large phial. The Old Etruscan religion, which was distinctly Euhemeristic, regarded the becoming a Lar as the first step to becoming a god. on which subject the following is of interest:--

"Les Lares, ou Lases, qui jouent un róle si important dans les anciennes religions de l'Italie, qui peuplent le monde romain, qu'on trouve partont, au foyer de la famille, dans la ville, à la campagne, sur

les routes--Lares familiares, urbani, rurales, viales, &c.; les Lares ont sans acun doute fait partie de la cosmogonie Etrusque. Leur nom seul semble le prouver, Larth on Laris est un nom et un titre d'honneur que l'on rencontre fréquemment sur les inscriptions funéraires de l'Etrurie. On lisait, d'ailleurs, dans les Livres Achérontiens qui faisaient partie de la doctrine de Tagès, que les âmes humaines pouvaient, en vertu de certaines expiations, participer a l'essence des dieux, et sous le nom de dii animales, ou âmes divines, prendre place parmi les Pénates et les Lares" (Servius ad Aen., iii., 168; cf. Fabretti, Gloss. Ital. s. v.). "Ainsi s'accomplissaient dans les croyances de l'Etrurie les mysterieuses destinées de l'âme humaine. Le Genius jovialis, après l'avoir recueille comme une émanation de la divinité, lui donnait entrée dans la vie; puis quand la mort venait séparer de la matière ce souffle divin, l'âme, éprouvée par les sacrifices, ou l'expiation, pouvait retourner parmi les dieux, et comme pénate elle remontait an rang on le Genius jovialis, ainsi que nous l'avons vu, était placé lui-meme" (L'Etrurie et Les Etrusques, par A. Noël des Vergers, Paris, 1862, vol. i., pp. 301, 302).

It will be seen by this extract that the still existing very singular belief that certain sorcerers' souls are sometimes reborn as mightier sorcerers than before, and from this proceed to be spirits, is exactly paralleled by the old Etruscan doctrine taught by Tages.

MÜLLER (die Etrusker, p. 81) says that CORSSEN (i., p. 346-7) "has erroneously attributed LOSNA, a goddess of the moon, to Etruria. She only occurs on a single mirror from Præneste (GERHARD, i., clxxi.), and is Latin (Lucna, Luna)."

"It is not for us to settle the question." But on asking my authority if she knew of such a being as Losna, I received the following reply, which I wrote down as uttered:--

"LOSNA is a spirit of the sun and moon--of both, not of the moon alone. When a brother debauches his sister it is always her doing. She loves to deride people gaily. When she has made her mischief she will appear at the table where a contadino is with his family, and laugh and say: 'Thou art a stupid fellow, thou knowest not that thy daughter is incinta (with child) by her brother, for thou didst once say, "E un grande piacere à fare l'amore col proprio fratello."' And when she has done this mischief she goes away singing, because she has caused discord in the family."

This startling myth has that in it which seems to prove great antiquity. The gypsies in the East of Europe have a legend that they are descended from the Sun and Moon; the Sun having debauched his Moon sister was condemned to wander for ever, in consequence of which they also can never rest. The natives of Borneo and the old Irish believed that the Man in the Moon is imprisoned there for the same deed. Finally, the Esquimaux have a similar story. These coincidences are fortuitous, but in any case they are remarkable. As for its character, I have already remarked that if these tales are truly handed down from the olden time they ought to be replete with sensuality-as they are. In

the spirit of collection, first established by GRIMM, nothing was preserved, much less sought for, which was not fit, I will not say for young ladies, but even for the nursery. In fact, fairy tales suggest nothing as yet, even to well-informed people, but innocent, sweet, pretty, and amusing Mährchen. But the old myths out of which these grew were nothing of the kind. However, it has come to pass that most collectors, influenced by fear of the Major-General Reader, quietly pass over this element which was, if not the great guiding influence in myths of what we may call the tertiary formation (or polytheism as it was passing into pantheism), was at least almost the chief. And if we wish to investigate the witchcraft of the first period, or this of the time when men had begun to regard Fertility and Reproduction, and such reviving influences as Light and Wine and gaiety as causes of life, we must turn over a vast amount of what is fearfully "shocking" to all who do not seek "abditis rerum causis"--into the hidden causes of things. For it was out of what could most terrify and revolt man that all primitive sorcery and much secondary Shamanism were formed, and if we would know Man's early history we must not, or cannot, avoid such study. Religious magic, at present, has dropped this portion of its first state, only retaining, or returning to, the early fear of infernal agency, or devils and hell, as the chief motive power in duty and incentive to worship. To fully understand all that now exists, and have a clear idea of what we really believe--which no living believer has--we must understand man in the past. Till we do we shall not comprehend the present nor clear the way for the future.

"Losna, that is Louna," says PRELLER, "appears on an Etruscan mirror with the half-moon associated with Pollux, on another monument as Lala, i.e., Lara, Δέςττοιυα {Greek Désttoiua}, with the sun-god Aplu." It is just possible that some tradition of such association with the sun may have given rise to the Tuscan story which is probably a mere fragment. In any case it is remarkable that in it there is an allusion to the sun and moon as an incestuous brother and sister.

I call the attention of the reader specially to the picture representing LOSNA. It is from a mirror which has for a century been frequently engraved in works on Etruscan art. This is now in my possession, and lies on my paper as I write. According to Corssen (Sprache der Etrusker, vol. i., p. 346), who refers to Gerhard's Etruscan Mirrors, iii., 165, Ritschl; Cavendoni, Schoene, Benndorff, Helbig, &c., as discussing it, it is from Praeneste, also that Lusna was the original name, and that Losna is a dialectical form peculiar to Praeneste.

This mirror had greatly interested me. I had purchased in London one book simply because it contained an engraving of it, and had made with great

LOSNA

(From the original Etruscan bronze mirror, now in possession of the Author.)

care three or four drawings of it from different works, with all of which I was dissatisfied, and when my publisher, Mr. Fisher Unwin, went over my illustrations with me here in Florence, March 5, 1892, I threw "Losna" out very unwillingly. I state simply the truth when I say that of all the mirrors ever made, it was this one in particular which I most desired to see, and I remember that it was much on my mind. On the afternoon of the following day I went by chance, or led by my Socratic demon, into a shop for odds and ends, or "Curiosities," and there in a glass case, and very much out of place, found an ancient Etruscan mirror--the very one which had been engraved, and which I so longed to see. I need not say that I purchased it at once. I should mention that the engraving here given is absolutely correct, having been made on a tracing or rubbing from the mirror itself, which is in a state of perfect preservation.

These mirrors were believed among the Etruscans to possess magic power. It is the same with the Chinese of the present day who make similar ones, the reason being this: The Chinese mirror, like the ancient, is polished on one side and has a picture, or more commonly an inscription, on the other. If we let the sun shine on the mirror and reflect it on a smooth white surface, the picture on the other side is distinctly visible in the reflection. I have heard explanations of this which did not satisfy me. About the year 1856 a daguerrotypist in the United States having cut two lines in a cross on the face of a copper plate found that though the cross was not perceptible on the back, yet that when reflected in sunlight it could be distinctly seen in the reflection. Hence I inferred that the pressure on the face hardened the metal throughout, which perfectly explains the phenomenon. I suppose that the Etruscan mirrors when new had the same quality. Of which invention there is no mention, not even by J. Baptista Porta in his many recipes for making marvellous "mirrors." The same may be made of glass by annealing the picture. That is, we take a pattern in hard glass, cast a bed of soft glass about it, and when cold grind off and polish the surface, which will seem uniform. But the reflection against the sun will show the light from the soft glass as duller than that from the hard.

All mirrors are, according to ancient and modern superstition, repulsive to witches, or evil spirits, and good against the evil eye and its like. Fascinators--like basilisks--had their own terrible glance turned against them if they saw themselves reflected, "Si on luy presente un miroir, par endardement reciproque, ces rayons retournent sur l'autheur d'iceux." As a lunar-solar goddess, I believe that Losna was peculiarly associated with the mirror as a magic object. Philostratus declares that if a mirror be held before a sleeping man during a hail or thunder-storm, the storm will cease.

Laronda in Tuscany is a very kind, benevolent spirit, who, strangely enough, is peculiar to, or who dwells in, caserme, or soldiers' barracks--"Sarebbe un spirito delle caserme dei militari. E molta buona."

She seems to be identified with the old Etruscan Larunda, or Lara, of whom Lactantius remarks: "Who can keep from laughter when he hears the silent goddess mentioned? 1 This is she whom they call Lara, or Larunda " (i., 20, 3 5). OVID speaks of her as the Dea muta, or silent goddess. But from a passage in PRELLER'S Mythology, I infer that she was specially known as good, since in reference to a prayer to her he remarks: "Here we plainly understand ein guter Geist--ein seliger"--a good or happy spirit.

But what is certainly very remarkable is that Larunda was especially the mother of the Lares compitales. "Compitum is a point where several roads meet. At such a place the Romans erected large buildings with passages and rooms, literally corresponding to modern barracks. "In them all the people round about met to discuss business and hold festivals." Therefore the Lares compitales were the guardian spirits of such large public buildings, where great bodies of men lived, or met. And Larunda was literally then, as Larunda is now, the chief spirit of what corresponds most accurately to the modern caserme which is now the only building in Italy which is quite like the ancient compitum. All of which PRELLER illustrates with much learning, and of all this I knew nothing when I first ascertained what I have written of the modern Tuscan spirit. And when we read that these ancient buildings were the resort of boxers, actors, gladiators, and of political clubs, we may well infer that soldiers also occupied them.

In the course of time stories grow up or are attached to names with which they have very little real connection. Such a legend relating to Laronda is the following:--

"Laronda is the folletto of the casernes. Once she was a donna named Rosa who, during her life, was devoted to soldiers. After a while the officers noticed it and forbade her frequenting the barracks, at which she was so much grieved that she fell ill, and was long confined to her bed. Then the soldiers themselves missed her sadly, and so arranged it that she could come secretly among them; so for a time all went well.

"Among these soldiers was one who had a sweetheart who was a zingara, or gypsy, as well as witch. Now the witch discovered that Rosa visited the caserme, and that all the soldiers were devoted to her, and that less for her beauty than for her gaiety and goodness; and with this the gypsy was ill-pleased and said to Rosa:--

"'Rosa, oh, Rosa, oh, fair Rosa! it is true that I am not so beautiful as thou art, for I am a gypsy. And thou art esteemed by all the soldiers and my own lover loves thee, so I beg thee not to frequent the barracks any more!

"'Per cio ti voglio pregare

Nelle caserme di non piú andare!'

Then Rosa replied frankly but resolutely, that she would yield nothing whatever to please her foolish jealousy, at which the other, in a rage, said: 'May my curse fall like lead upon thy head, nor wilt thou live long--but one year do I give thee.

"'E fin anno che tu camperai,

Tu non avrai che pene e guai.

"'A year thou'lt live in pain and grief,

Ere death will come to bring relief.

"'And since thou lovest soldiers so well, thou shalt have no rest after death, but shalt become il folletto della ronda (the spirit of the patrol, or night-guard), and LA RONDA thou shalt be.'

"As she threatened so it all came to pass, and the soldiers grieved for her death. But while they were sorrowing they were suddenly amazed to see at a window the apparition of a lady of great beauty clad in white, who said:--

"Io sono la bella Rosa, I am the beautiful Rosa--but now I am dead I have become the Folletto della Ronda of the soldiers, and when night flees from the world of the eternals I will come to seek you, and when you hear me call, then open the windows to La Ronda."

There will be many to whom this adaptation of a modern pun to a word will quite suffice to destroy all connection with the classic Larunda. In this way we might utterly invalidate all and any tradition whatever, just as VOLTAIRE declared that the petrified shells found on mountain-tops had probably been scallop shells dropped by pilgrims from the Holy Land. But Laronda was from very ancient times the guardian spirit of the public building, while this story turns upon a mere resemblance of the word to a technical term with a very different meaning. I think it most probable that some ingenious but ignorant person, hearing of Laronda, adapted it to the word for patrol or "round."

I have since heard it asserted that Laronda may be, or is, the spirit of any large building frequented by many people, such as a hotel. This seems to be the old and generally entertained idea, while I have no guarantee whatever that the story is not a mere modern fabrication founded on a jest.

If Larunda be modern because there is a modern story fitted to the name, then of course any myth may be punned or conjectured out of existence.

On asking if such a word as Lemures was known, I was told that Lemuri sono i spiriti dei campo-santi--"Lemuri are the spirits of the churchyards." This

clearly enough identifies them with the Latin Lemures, which were the same as the Larvæ, or the unhappy and terrifying ghosts of those who have died evil deaths, or under a ban, to which there are innumerable allusions in all Latin writers. 1

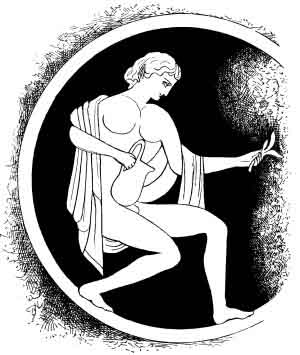

Tago is a spirit whose name appears to be known only to a few old people. He is described as a spirito bambino, or appearing as a little boy. Of him Favi Gustavo declared Tago is a spirit who is invoked, when we see children suffering, with an invocation which causes them to recover their health. But this prayer I do not recall so that I could write it."

Another authority informed me that there is a spirito bambino, or spirit like a boy, who is, however, a wizard. His name is Terieg'h (harsh and guttural and uncertain). He comes up out of the ground, and predicts the future or tells fortunes. As these are the only spirits in such form I suppose them to be the same being.

The name Tago will naturally suggest to the scholar that of Tages, "the wise Etruscan child plowed from the earth," whose history is given in detail by Preller and many more, but by no one so succinctly or elegantly as by Petrarch in his Italian-Latin. This child, one day, as a peasant was ploughing--Hetrusco quodam arante in agro Tarquiniensi--leapt from the furrow, an infant in form but with an old man's head and wisdom--puerili effigie sapientia senili--and proceeded forthwith to astonish everybody by his prophesies and instructions in what was then religious wisdom, but what we should now call magic. And it was indeed from his books and teachings that all Roman divination and sacred observances were drawn. And as Etruscan lore began with him, it would be indeed deeply interesting if we could prove that he still lives in his Etrurian home as Tago or Terieg'h. Truly such survivals as these may not be of the fittest for the spirit of the age, but it is befitting that they be recorded, if only to show the extraordinary manner in which they are frozen up in popular tradition to be now and then

TAGES

(From the Etruscan Museum of Gori.)

thawed out to some seeker. But whether Tago or Terieg'h really be Tages I leave for others to settle. Davus sum non Œdipius. For, as Johannes Practorius says in his Anthropodemus Plutonicus, that "all this story of Tages maybe a mere fable wherewith the devil, after his fashion, hath deluded and betrayed man with a wonder, that he might use the many superstitions which had their beginning in Tages, his fortune-telling and sorcery."

Hæc loca capripedes, Satyras, nymphasque teneræ,

Finitimi fingunt et FAUNOS esse loquntur,

Quorum noctivago strepitu."

LUCRETIUS, iv., 584

To a person of humanity and tender feelings there is something very touching or indescribably pitiful in the manner in which the people in Europe clung to their old gods and resisted Christianity. For it is not true at all, as is generally misrepresented, that they gladly took to the mystical, abstract, Hebrew-Persian Roman Catholic religion of professed love, and priestly and feudal oppression which they did not understand. Nor did they find any attractions in its making a duty of obedience to cruel feudal tyrants, of asceticism, fasting, and dread of the devil. It was all forced on them, and they long resisted it. Despite cruel persecution (as Horst and Michelet observe), the peasants persisted in their devotion to the poor old forbidden gods, and every few years, so late as the fifteenth century, councils thundered at, colleges condemned, and priests burned people for heathen sacrifices. And they were not a few who thus clung to the ancient faith. They were all over Europe, and, as I have shown, there are some still left in the Toscana Romagna.

This old religion of nature was congenial to the people because they understood and deeply felt it. They had, as I hope the reader has, an impression that there is a spirit in the pathless woods, deep song in silent shade, life in the long-forgotten land of early days--homes of visions in the old grey rocks with possible portals through which elves or their own elfin thoughts may pass. They know the Voice of the Waterfall, and what the stone said when it was thrown at twilight into the well or silent pool "under the stars," and why the laurel crackled when it burned, and what words it said--these were all spirits, and they had learned the spirit-language from their fathers. There was an indescribably delightful, companionable sense in believing that there was a jolly, mischievous, familiar goblin who lived in the fire, or haunted the fireplace, who teased the girls and bothered the boys, and was "so sociable." All of these were like themselves, and within their natural comprehension,

and they would believe in them because, as they must adopt some kind of supernaturalism, they took that which was most natural, sensible, and congenial to them. A haggard, bleeding, pallid spectre, everlasting goody-goodiness of

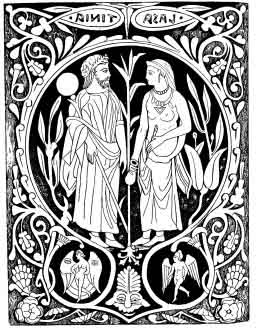

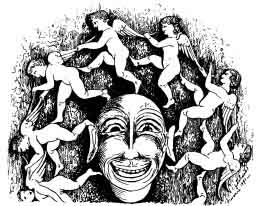

ETRUSCAN RURAL DEITIES

Madonnas, and the agony of tortured saints with no end of fasting and prayer, are not congenial to us, nor did healthy humanity ever accept them in loving earnest, as it did the old heathen gods. The whole history of the Middle Ages--or

you may continue it later an you will--is one of mankind making believe that they believed in misery. And the proof of it, reader, is very plain, and it is simply this-that wherever and whenever Christianity has any "superstitions" or elements quite in common with the old heathenism, there people are most truly religious. "Man is properly the only object which interests man;" he feels and lives in Humanity and Nature, and never truly cares for what is remote from or is forced into these.

You and I, reader, feel the true spirit of old heathen religion when we walk in the forest and skirt the line of " thus far--and then no more--the language of the sounding sea to the sands upon the shore," or arc sitting by the fire in silent night. We do not make it into goblins, but our own thoughts and memories become to us quite the same as spirits, for we feel or see how we can give them life or expressed thought in act or words. Make this literal--not a mere figure of speech--and then, friend, you will be as happy as a heathen suckled in a creed outworn--yea, quite as well off--which was all that Wordsworth wished for, and was not unlike the desire of François Villon, who yearned for the ladies of the olden time.

It is a great pity, but pity 'tis 'tis true, that owing chiefly to the affected-sentimental, or false influences of mediæval religion and its resultant "art," we do not really know what we ought to admire or "feel beautiful" over, or enthuse about, till somebody has told us how. Then we go and "do it." We do it by going to see all the places prescribed by the hotel directions, "there and back, twenty-five francs for a party of four," and duly admiring them, and pass by without note a hundred spots even more beautiful. And verily such a doing thereof as I behold here among tourists in Italy to see what it is "the thing" to see (i.e., everything, according to Ruskin, Bædeker, and Co.), might draw tears from a millstone. A child or a peasant is better off--it or he takes Nature as it comes--naturally. The tourist who goes by precept may think that he can feel nature as a child, but he does not. You cannot serve God and Mammon together.

This old spirit of unaffected feeling of nature without " culture " is deeply impressed in all this Tuscan-Etruscan folk-lore, and I would that my heart could utter the thoughts which it often inspires. It was all summed up for the ancients in the single word Faunus. Faunus and the Fauni were the incarnation of forests, streams and fields, fairy-life and flowers. Therefore I was glad to find that this deity, who is only another form of Pan, still lives in the Romagnola, as is set forth in the following passages.

"FÁNIO is a wizard who comes in the form of a spirit." This appears to be the Euhemeristic conception of all the spirits in this very primitive Tuscan

mythology. First a wizard, or a man of power on earth, who is remembered after death, and then is supposed to still haunt the scenes of his former life. What Fánio does was narrated as follows:--

"Fánio frightens peasants in the woods. He appears as a man leaping up with his hands wide open, thrown forward, or looks like a devil, scattering fire, and then laughs at the fear which he has caused. And when there is a wedding he often anticipates the bridegroom in his kisses, and when the husband comes and would embrace his wife he feels invisible blows and cuffs, which put him in a rage, when Fánio bursts out laughing, and says:--

"'Vuoi sapere chi sono?

Sono lo spirito Fánio,

Che cio che m'e piacuto in vita,

Mi piace at altro mondo;

Mi dovresti ringraziare,

Che ti ho risparmiato tanta fatica!'

'Who I am?--if you would know,

I'm the spirit Fánio!

What in life once gave me bliss,

Pleases me as much in this;

And I think that thanks are due

Unto me for helping you!')

Then if the husband is vexed at this, and if his wife is angry and curses the goblin, he only torments her the more and returns as a nightmare to disturb her sleep."

It is not difficult to recognise in this Fánio the Faunus of the Latins. All of the characteristics attributed to him in the account agree accurately with what PRELLER relates:--

"In some phases of popular belief Faunus appears as nearly allied to Silvanus, as a spirit of the forest, who lurks in deep shadows, in hidden caverns, or by rustling waterfalls, where he predicts fortunes or catches birds, and chases the nymphs. . . . The fauns as a class were much given to teasing and tormenting mortals in their sleep, so that they sometimes appear altogether as annoying imps--like the nightmare to us--against which attacks people used all kinds of roots and quackeries, especially the root of the forest-peony (Waldpäonie), which had to be dug by men by night, else the great wood-pecker would peck out their eyes. But, above all, the women had to be on their guard against the fauns and Silvani, for these lecherous wood-goblins readily slipped into their beds, whence the popular name of Incubus for them." "From their lechery they were called Faunificarii. 'Vel Incubones, vel Satyros, vel sylvestres quosdam homines quos nonulli Faunes picarios vocant'" (Hieron. in Isai, v. 13, 21).

These fauns and silvani of Tuscan belief are very much allied to the mischievous household goblins. They all make naughty love to women, and act as incubi, or nightmares, and cause wild dreams. Quite the same spirits were known of old in Assyria. Lenormant says (Magie Chaldaienne):--

"To the Incubus and Succubus was joined the Nightmare in the Accadian Kiel-udda-karra, in the Assyrian, Ardat. . . . It is probable, judging from its name, that it was one of those familiar spirits which

FAUN (On a patera. (Etruscan) Museum, Florence.)

make the stables and the houses the scene of their malicious tricks; spirits whose existence has been admitted by so many people, and which are still believed in by the peasants in many parts of Europe."

It may be remarked that nearly all the spirits which occur in this peasant mythology are of the nature of the fauns. Also that while the Romagnola contadino has retained old Etruscan names of gods, and those of the minor sylvan and rural deities, such as Sylvanio, Fano, and Paló, he has not the great Latin gods. Bacchus is commonly enough sworn by, but I could gather no information regarding him, save that he was "the god of wine, and therefore must be the same as Faflon." The best treatises which I have met on the Fauns, Satyrs, Silvani, Incubi, &c., form chapters in that strange work by C Bauhinus, 1667, entitled De Hermaphroditis, &c.

The peony was, on account of its red colour, regarded as great protection against the fauns as nightmares. PRÆTORIUS (Anthropodemus Plutonicus; Von Alpmännrigen, 1666) mentions that people, to keep away the Incubus, wear round their necks, or hanging from them, "flints, corals, or peony roots."

It is worth observing that the ceppo sacro, a holy log of wood which is burned on Christmas Eve--the yule-log of the North--is taken with due observance and incantation to the fauns or other spirits of the forest. For, despite his immoral and mischievous conduct, Fánio is a general favourite, as was Faunus of old, for many reasons not too far to find, but not worth specifying.

In a work on Faunus, Del Dio Fauno, e de suoi segnaci, di Odoard Gerhard (Eduard Gerhard, Naples, 1825), the author declares that whatever deity he may have been, mixed and mingled as he was with others, is not difficult to determine. The truth is that all these minor spirits of forests and fields, firesides and bedrooms, were naturally familiar and mischievous creatures, as much alike as romping schoolboys, therefore all nightmares; teasers of girls, therefore seducers, and consequently wanton and gay. They were in reality more distinguished by flames than by natures.

This word refers to an herb or small plant which, as in the case of rue, rosalaccio, and others, is by mysterious association also a fairy. Querciuola is properly, in Italian, a small oak-tree, but, as in many other instances, it has been transferred from one plant to another in Romagnolo. What I learned of it (given to me with specimens of the plant), is as follows

"When one has quarrelled with a lover, one should go and sit beside the plant called Querciola, wherever it is growing, because the fairy of that name is a great friend to lovers. So when one is distant, or separated, be it as to the heart or place, the other sits by the herb and sings:

"'Fata Querciola!

Sei tanto bella quanto buona

A ti mi vengo raccomandare,

Che il mio bene

A mi tu faccia ritornare.

Fata Querciola!

Ai fatto tanto bene

A tante persone

Anch' io voglio sperare

Che di me non ti di me

Vorrai dimenticare.

Fata Querciola!

Sei tanto bella e altra tanto buona

Ti chiedo una grazia sola

E spero non me la vorra negare,

E lo mio amore

Mi farai ritornare.

Fata Querciola!

Sofrirei tante pene

Se da me non tornasse il mio bene,

Ma da me le conviene si ritornare,

Perche la fata me l'ha promesso,

Di farlo ritornare sotto al mio tetto.

("'Fairy Querciola!

Thou art good as fair

Let me hope and not in vain,

That thou wilt send happiness

Unto me again!

Fairy Querciola!

Thou hast blest so many,

Send a blessing unto me,

Let me hope that I, though humble,

May not forgotten be!

Fairy Querciola!

Fair as thou art good

One favour I implore,

Which I hope thou'lt not deny

Make him who was my lover

Return to me once more.

Fairy Querciola!

I shall suffer sore

Unless my love as lover

Comes back as once before.

But, fairy, thou hast promised me,

And what thou sayst will surely be,

He'll seek my roof once more.'")

Querciola, or Querciuola, as the name of a nymph or sylvan spirit, is clearly enough closely connected with that of Querquetulana, an old Roman or Italian simile for Vira (which see), a wood-nymph; though the term, like Querciola,

SETHLANS, VULCAN, AND THE TROJAN HORSE

refers especially to a dryad, or spirit of an oak. So FESTUS observes (PRELLER, R. M., p. 89, second edition): "Querquetulanæ Viræ putantur significari nymphæ presidentes querqueto virescenti, quod genus silvæ indicant fuisse intra portam quæ ab eo dicta sit Querquetularia." Querciola is therefore clearly a dryad.

These Querquetulanæ have an apparent, or barely possible, survival in the spirits called Querkeln in Bavaria. They emigrated from that country, passing over the river Main by the village of Wiesen (Bayerische Sagen von Fried. Panzer, Munich, 1848).

I am not sure whether this name is Sethano or Sethlrano or Settrano, nor have I been able to learn more than what is contained in these lines:--

"Settrano is the spirit of fire. He is remembered by all here. They know a proverb (i.e., a saying, invocation, or spell) which is repeated. When they do not wish the fire to burn they invoke (se voca) that spirit,"--SETTE TICO.

Of all these spirits there are invocations and tales, but I have not in all instances been able to collect them.

Sethlans was the Etruscan Vulcan.

83:1 In all cases where the text is in metre the original was chanted or intoned.

94:1 "Quis, quum audiat deam Mutam tenere risum queat? Hanc esse dicunt, ex qua sint nati Lares, et Laram nominant, vel Larundam." Which is what an ancient heathen might have said at seeing a Spanish Virgin Mary in an old French bonnet, or even some of her similitudes here, in Italy, which are ten times sillier and more laughter-moving than the rudest works of Roman times.

96:1 "Verum illi manes, quoniam corporibus illo tempore tribuuntur quo fit prima conceptio, etiam post vitam iisdem corporibus delectantur, atque cum iis manentes appellantur Lemures" (MARTIAN, Cap de Mess., ii., 9, p. 40; ap. MÜLLER). "Lemures larvæ nocturnæ et terrificationes imaginum et bestiarum" (AUGUSTIN, c. Dei. ix. II; ap. PRELLER). "Lemures umbras vagantes hominum ante diem mortis mortuorum et ides metuendus " (PORPH.; ap. PRELLER).