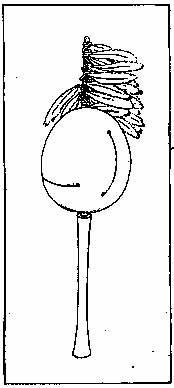

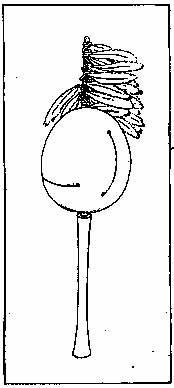

FIG. 4. Piai's rattle (Arawak), Pomeroon.

Sacred-Texts Native American South American Index Previous Next

Medicine-men practise what they preach: Names (285); respected and feared both alive or dead and may be given offerings (286), but occupy no position necessarily distinctive, as captain of tribe (287).

Insignia and paraphernalia: bench (288), rattle (289), doll or manikin, identical with idol or zemi of Antilleans (290), quartz crystals (291); miscellaneous kickshaws (292).

Office, hereditary (293). Female doctors (294). Consulting-room (295). First Piai (296). Apprenticeship and Installation (297).

Power over Spirits: of animals (298), of himself (e. g. invisibility) and of other Indians (299).

As interpreter of dreams (300); seer or prophet (301); his general versatility (302-303); guardian of the tribal traditions (304); the giver of personal names (305); his treatment of sickness and disease (306).

Disease and treatment: signification (307); usual treatment by Arawak piai (308); by Carib (309); by Galibi (310); by ? Oyampi (311); by Makusi (312); by Indians of Caracas (313); by Carib Islanders (314). Spirits specially invoked in cure (315); objects extracted from patients (316); dieting of patient's relatives and family (317); medical fees (318); Quack doctors (319).

285.* There is abundant evidence that the medicine-men practised what they preached, and had every confidence in the powers with which they had been intrusted. "They practise those incantations over their own sick children, and cause them to be practised over themselves when sick" (BrA, 117). "They act the farce on themselves when they are disordered: a practice which has not a little contributed to overthrow all doubts of the sincerity of their pretensions" (Ba, 314). "The piai himself believes in it: one will put himself in the hands of another when sick" (Go, 13). Schomburgk was "convinced that the piai believes in the efficacy of his witchcraft as firmly as his protéges" (ScR, II, 146). The real causes of the existing prejudice against the medicine-men are not far to seek, and have often been clearly expressed. "As doctors, angurs, rain-makers, spell-binders, leaders of secret societies, and depositaries of the tribal traditions and wisdom, their influence was generally powerful. Of course it was adverse to the Europeans, especially the missionaries, and also of course it was generally directed to their own interest or that of their class; but this is equally true of priestly power wherever it gains the ascendency, and the injurious effect of the Indian shamans on their nations was not greater than has been in many instances that of the Christian priesthood on European communities" p. 328 (Bri, 55). On the other hand, there is not a single recorded instance of the Guianese Indian priesthood ever having submitted those of their people holding religious views different from their own to either torture or the block. The Creole term for the priest-doctor is piai-man, a hybrid that seems to have been first recorded by Waterton in the form of pee-ay-man, who is an enchanter; he finds out things lost (W, 223). In its simple form, the word of course came into use much earlier, and is seemingly derived from the Carib piache, which Gumilla employs, and is still met with among the Pomeroon group of these Indians as piésan. Brett (Br, 363) derives it from the Carib word puiai, which denotes their profession. The Akawais call it piatsan. Dance seems to derive the name from that of the tribal hero, Pia (Sect. 41). Crévaux in Cayenne speaks of piay, de Goeje in Surinam of piai, and Bates, throughout the extent of the Amazons visited by him, of pajé. The Warrau word for the priest-doctor is wishidatu (wisidaā, according to Brett), similarly applied to the kickshaws. In some of the Orinoco nations, they call these men Mojàn: in others Piache: in others Alabuqŭi, etc. (G, II, 25) The Piapocos Indians of the lower Guaviar River speak of them a Kamarikeri (Cr, 526); the Caribs of the lower Caroni River as Marirri (AVH, III, 89), and the Island Caribs as Bové (RoP, 473). The Arawak designation is of equal interest and also of extended range: it is Semi-tchichi or Semi-cihi, the same term applied generally to the kickshaws and various apparatus employed in the pursuit of the craft (Sect. 93).

286.* Both alive and dead, the medicine-men had the respect and fear of the community. They were the teachers, preachers, counsellors, and guides, of the Indians; "regarded as the arbiters of life and death, everything was permitted, and nothing refused them; the people would suffer anything at their hands without being able to obtain redress, and with never a thought of complaining" (PBa, 210). They thus lived "in clover," (G, II, 24), better than all the rest of the people (St, I, 399). And yet in a sense they were restricted: they must not partake of the flesh of the larger animals, but limit themselves to those only which are indigenous to their country (ScR, I, 173); they had religiously to abstain from certain fish and game (PBa, 211); no animal food was publicly tasted by these priests, while they abstained, even more strictly than the laity from the flesh of oxen, sheep, and all other animals that had been transported from Europe (Sect. 247) and were "unnatural" to their country (St, I, 399). They were said to renew their piai power from time to time by drinking tobacco juice, but in doses not so strong as at the time of installation (PBa, 211). As stated above, even dead the medicine-men were still respected.

They also keep the dead bones of these sorcerers with as much veneration as if they were the Reliques of Saints. When they have put their bones together, they hang them in the Air in the same cotton beds those Wizards use to live in when alive. [Da, 98.]

Bates gives a curious example of such veneration and sanctity, met with at a spot on the Jaburu channel, Marajo Island, at the mouth of the Amazon, "which is the object of a strange superstitious observance on the part of the canoe-men. It is said to be haunted by a Pajé, or Indian wizard, whom it is necessary to propitiate, by depositing some article on the spot, if the voyager wishes to secure a safe return from the sertaô, as the interior of the country is called. The trees were all hung with rags, shirts, straw hats, bunches of fruits, and so forth. Although the superstition doubtless originated with the aborigines, yet I observed, in both my voyages, that it was only the Portuguese and uneducated Brazilians who deposited anything. The pure Indians gave nothing; but they were all civilized Tapuyos" (HWB, 115). Koch-Grünberg gives a similar example on the River Caiary-Uaupes (Upper Rio Negro), where the practice is undoubtedly observed by the Indians (KG, I, 237), while Coudreau (II, 404) has observed it on the Rio Branco. (Compare the protective charm against the Curupira, etc., in Sect. 109.).

287.* It sometimes happened that the captain and the piai were one and the same person, as in Cayenne (PBa, 208). But on the other hand, however great his abilities, the medicine-man did not obtain any distinctive position, as head of the farnily, through his proficiency (Go, 14). Bancroft (310) says that in almost every family, there is a person consecrated to the craft. There was apparently nothing characteristic about the piai in the way of ornament or decoration. I can find no confirmation of Bernau's statement that the novitiate's "right ear is pierced, and he is required to wear a ring all his lifetime" (Be, 31).

288.* The insignia and "stock-in-trade" of the medicine-man, in his highest stage of development, comprise a particular kind of bench, a rattle, a doll or manikin, certain crystals, and other kickshaws, generally something out of the common, all except the first mentioned being packed away when not in use, in a basket, or pegall, which is usually of a shape different from that employed by the lay fraternity. The peculiarity of the basket among Arawaks and Warraus lies in both top and bottom being concave. St. Clair (I, 330) reports that on the Corentyn, among Arawaks, he came across the "magical shell" (rattle) supported by three pieces of stick, the ends of which were stuck into the ground, in the middle of the floor; it is not clear, however, whether in this situation the implement was being used or not. At any rate, all the insignia were taboo to the common folk and were kept out of harm's way in a special shed, the piai's consulting-room, p. 330 so to speak. Were they to be profaned, they would lose their intrinsic virtues, while the delinquents would suffer misfortunes of various descriptions. The bench (the ha-la of the Arawaks), plate 5, differed from the ordinary article of furniture usually met with in Indian houses, in being larger, often painted, and carved in fanciful designs of various animals, but little is known concerning the why and wherefore of the selection of the particular beast; thus, I have seen the turtle, alligator, tiger, and macaw more or less faithfully represented on such Warrau and Arawak divining-stools.

FIG. 4. Piai's rattle (Arawak), Pomeroon. |

289.* The rattle, maráka (an Arawak word), the shakshak of the Creoles, differs somewhat in shape, size, and ornamentation throughout the various tribes. It consists essentiany of a large cleaned-out "calabash," containing stones and other objects, through which a closely fitting tapering stick is run from end to end by means of two apertures cut for the purpose (fig. 4). This gourd shell (Crescentia cujete Linn.), which may or may not be painted in various colors, is provided with certain small circular holes as well as with a few long narrow slits, both kinds of openings being too small to allow of the contents (either quartz-crystals or a species of agate) dropping out. Seeds may be employed with or without the stones—small pea-like seeds variegated with black and yellow spots which, it is commonly believed, will occasion the teeth to fall out if they are chewed (Ba, 311), or hard red ones (StC, I, 320). But whether seeds or stones, they usually have some out-of-the-way origin; the former, for instance, may have been extracted from the piai teacher's stomach (PBa, 208); the latter may be the gift of the Water Spirits (Sect. 185). According to a Kaliña, the power of the maráka lies in the stone contained therein (Go, 14). The thicker, projecting part of the stick constitutes the handle, to prevent its slipping; it may be wrapped with cotton thread. The exposed thinner end is ornamented with feathers, as those of the parrot, inserted in a cotton band, which is then wound spirally on it. An Arawak medicine-man assured me that the feathers must not only be those of a special kind of parrot (Psittacus œstivus), but that they must be plucked from the p. 331 bird while alive. A string of beetles' wings may be superadded. Gumilla (I, 155) states his belief that the Aruacas [Arawaks], the cleverest of the Indians, were the inventors of the maráka, which even in his day, some two centuries ago, had "also been introduced into other nations." From the fact that, according to Indian tradition (Sect. 185), the original rattle was a gift from the Spirits, Dance (290) accounts for the great veneration in which it is held even by Christian converts who have ceased to use it. Brett (Br, 364) confirms this, saying that there are Indians who fear to touch it or even to approach the place where it is kept. I have had personal experience that the same holds true today in the Pomeroon. So again, on account of the agates being put to use in the construction of the apparatus, Bancroft (21) records how these white and red stones remain untouched where they are found in abundance above the cataracts of the Demerara. In speaking of the Warrau rattle, Schomburgk says: "If the sick man dies, the piai buries his rattle also, since it has lost its power now, and with the sick person its healing properties die" (ScR, I, 172). I can not, however, find this statement anywhere confirmed.

290.* Gumilla (I, 155) says that the medico makes the Indians believe that the maráka speaks with the Spirit (demonio), and that by its means he knows whether the sick person will live or not. This statement does not exactly agree with the evidence handed down to us by other reliable authors, nor does it quite agree with what I have been taught and have seen put into practice. The object of the rattle is to invoke the Spirits only; it is rather the business of the manikin, or doll, to give the prognosis, to lend assistance, etc. Mention is made of such an object in Timehri (June, 1892, p. 183): "Some few months ago, a gold expert and prospector while traveling along the Barima River, came upon the burial-place of an Indian Peaiman or Medicine-man. The house under wliich the burial had been made was hung round with five of the typical peaiman's rattle or shak-shak, and over the grave itself was placed the box of the dead man, containing the various objects which had been the instruments, or credentials, of his calling. The contents of this box . . . were a carved wooden doll or baby." The doll, or manikin (fig. 5), which I saw used for the purpose on the Moruca River, was a little black one about 2½ inches long, balanced "gingerly" on its feet, which bore traces of having been touched with some gummy substance: if during the course of the special incantation it remained in the erect position, the patient would recover, but if it fell over, this would be a sure sign of his approaching death. In parts of Cayenne the doll is replaced by the Anaan-tanha, or Devil-figure (Sect. 311), which is unmercifully thrashed with a view to compelling the Evil Spirit to p. 332 leave the invalid. The identity of this mainland doll, or manikin, with the idol, or cemi, of the Antilleans has already been indicated (Sect. 93).

291.* The crystals are employed for charming, bewitching, or cursing others, though the references in the literature to their application in this manner are exceedingly scarce. Indeed, I can call to mind only the following from Crévaux (554): "I notice on the neck of one of them [Guahibos of the Orinoco] a bit of crystal set in the cavity of an alligator's tooth. The whole has the name of guanare. . . . It is with this guanare that the Guahibos throw spells (jettent des sortilèges) on their hated neighbors, the Piaroas. . . . Every mineral that presents in its lines and shape a certain regularity is to

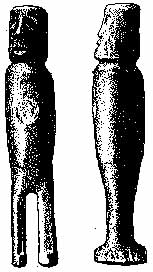

FIG. 5. The piai's manikin, or doll (Arawak), Moruca River. (Note the chest-ornament; see fig. 6.) |

292.* With respect to remaining kickshaws, Pinckard (I, p. 505) says: "And having faith in spells, they make little decorated instruments, of tender rushes about a foot long, which their physicians or priests called Pyeis employ together with other magical implements, as wands to drive out these demons of Ill." These instruments I have been unable to identify thus far. Finally, on the authority of the old medicine-man who taught me the greater part of what I know concerning the practice of the art, a "charm" of some description was worn on the chest suspended by a cord hung round the neck (Sect. 93). The one that my late teacher (Bariki) employed is flat and oval, made of some resinous material, and ornamented on one side with the incised figure of a female frog (fig. 6). It had been given Bariki by his grandfather when the latter taught him his profession, and when the old man died, he left it to me. In the extract from Timehri (1892, p. 184) above quoted, where is to be found a list of the kickshaws appertaining to the piai-man's stock-in-trade, is mentioned: "a neatly carved representation, in reddish quartz, of a dog sitting on its haunches p. 333 and holding its front well up. In this figure the base of the fore legs is occupied by two clearly-bored holes, into which, evidently, it had been the custom to fit strings by which to pull the little object along on the ground, just as toys are usually drawn along by small children." It seems to me far more reasonable, under the circumstances, to suppose that this object was the doctor's chest-ornament just referred to. There is absolutely no evidence of any Guiana Indian toy being used in this manner, and it is ridiculous to believe that the vast amount of labor necessarily involved in carving

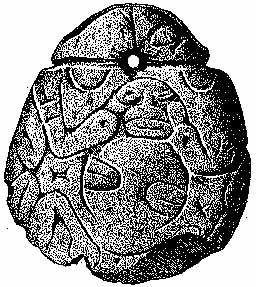

FIG. 6. The piai's chest-ornament (Arawak), Moruca River. |

293.* The office of the medicine-man appears to have been hereditary and to have passed to the eldest son (Ba, 316). If he has no son the piai picks a friend as his successor (ScR, I, 172), although the same authority (Schomburgk) elsewhere states that, under these circumstances, he chooses the craftiest among the boys (ScR, I, 423-4). It is likely that the secrets and mysteries of the profession may also have been imparted to outsiders for a consideration. I happen to have known one of the fraternity who taught another his profession for the sum down of eleven dollars together with the gift of his daughter. Im Thurn (334) says: "If there was no son to succeed the father, the latter chose and trained some boy from the tribe—one with an epileptic tendency being preferred. . . . It has been said that epileptic subjects are by preference chosen as piaimen, and are trained to throw themselves at will into convulsions." Perhaps this idea had its origin in the fact that through the use of a narcotic powder, the piais can throw themselves into a condition of wild ecstasy (ScR, I, 423-4): several such powders were known to some of the Guiana Indians, as the Yupa (G, I, 181), etc. On the other hand I can find no references in the literature to the choice of epileptic subjects; furthermore, the unlikelihood is turned into impossibility, when it is borne in mind that the victim of such a convulsion would be unconscious during its progress.

294.* Occasionally the piai may be a woman. Thus, I knew an old Warrau dame who used to practise her profession in the neighborhood of Santa Rosa Mission, Moruca River, under almost the very nose of the unsuspecting Father. On the authority of Joseph Stoll, Arawak, catechist at St. Bede's Mission, Barama River, young women, certainly among his own tribe, used to be trained in the same manner as the boys for the profession of piai: his own grandmother (on the father's side), and his father's cousin were both trained piai-women. On the other hand, I can find no references whatever to woman "doctors" throughout the early literature of the subject.

295.* The medicine-man usually possesses a little outhouse (Pomeroon and Moruca Rivers), plate 6, in which he keeps his various insignia: the Warraus call it hebu-hanoku (Spirit-house). This building is of course taboo, as indicated by a bundle of kokerite leaves hung over the entrance. As a matter of fact, I have never seen the doctor's "consulting-room" in the Pomeroom District built of any leaves other than kokerite. At Savonette, Berbice, the "consulting-room," so to speak, must have been a somewhat more complicated structure, for the use of medicine-men in common. "Near to the cabins that were inhabited, we observed a detached building inclosed on all sides, forming a single room, into which light and air were only admitted at the doorway. Upon inquiry we learned that this was devoted to the use of the sick—not as a hospital, but as a temple of incantation, for the purpose of expelling disease" (Pnk, I, 505). On the Amazons, Father Acuña (98) also leads us to believe that there was in each settlement one special building for the use of all these doctors: "There is a certain house devoted to the use of these sorcerers, in which they perform their superstitious exercises, and converse with the Devil."

296.* The original piai forms the subject-matter of legends with which Arawaks, Warraus, and Caribs are all more or less conversant; members of all these tribes assure me that tobacco was brought here from the islands, but I will let a Warrau give two of the versions:

*THE HUMMINGBIRD WITH TOBACCO FOR THE FIRST PIAI (W)

A man had been living with a woman for a long, long time: she was very good at making hammocks, but could not bear a child. So he took unto himself a second partner: by her he had a baby and was now happy. The infant, Kurusiwari, grew apace, and while the step-mother would be weaving her hammock, it would often come and hang on the suspending cord and slacken it. The old woman stood all this little annoyance for some time, but one day when the child was even more mischievous than usual, she said, "Go away, and play over there." It obeyed, went to a distance, but soon toddled back and once more interfered with the string. The woman now pushed the youngster aside, and in so doing it fell and cried. No one took notice of the incident and no one saw it toddle out of the house. All this time its father and mother were lying together in their hammock, and it was late in the p. 335 day when its presence was missed by them. The child was nowhere to be found, so they went over to a neighbor's and there they saw their little one playing with some other children. They explained their errand to the house-people, how they had come to seek their little one, and so, one thing leading on to another, they entered into an animated conversation, and forgot all about their real business, with the result that when they did finish talking, not only was their own child, Kurusiwari, but also one of the house-children, Matura-wari, nowhere to be seen. So the four parents started in search of the two little ones, and went to a neighbor's house, where they saw them playing with a third child, Káwai-wari. But the same thing happened at this house as at the previous one—the parents all got into conversation, and forgot their real business until finally they found all three children missing. It was a case now of six parents searching for three infants; but at the end of the first day the third couple abandoned the search, and at the end of the second day the second couple did likewise. In the meantime the three children had wandered on and on, making friends with the marabuntas [wasps], which in those days talked but did not sting. It was these children that told the black ones to sting people, and the red ones to give them fever in addition. And it was when the children arrived at the seashore that the first pair of parents met them. However, by this time they were children no more, but big boys. When the parents expressed their pleasure at having found them at last and of course expected them to return home, the leader of the three—Kurusiwari, the boy who had been lost from the first house—said: "I can not go back. When my stepmother pushed me, I fell down and cried, while you would not even look at me. I will not go back." But when both father and mother implored him with tears to return, he relented, and promised them that if they built a proper hebu-hanoku [lit. Spirit-house], and "called" him with tobacco, they should see him. He and the two other boys crossed the seas, and the parents returned home. No sooner had the latter arrived there than the father started building the Spirit-house, and when completed he burnt pappaia leaves, and cotton leaves, and coffee leaves, but all were of no use—there was no "strength" in any of them, and this strength could be supplied only by tobacco. But in those days we had none of this plant here: it grew far away out in an island over the sea. I do not know whether this island was Trinidad, or not, but we Warraus call it Nibo-yuni [lit. Man-without] because it was peopled entirely by women [cf. Sect. 333], according to what the old people tell us. Well, the sorrowing father sent a gaulding bird [Pilerodius] over to fetch some of the tobacco seed: but as it never returned, he despatched various kinds of sea-birds one after another, and they all met with the same fate. They were killed by the watch-woman as soon as they alighted on the tobacco-field.

Giving up all hope of ever seeing any of his messengers again, he went to consult a brother, who brought him a crane. This bird went to roost down near the seashore so as to have a good start on the following morning. While resting there, his little friend the hummingbird came along and asked him what he was doing. "Getting ready for the morning," he replied; "I have to fly over to Nibo-yuni and fetch tobacco seed." The hummingbird suggested his going instead, but the other regarded the proposal as absurd, and reminded him that his boat was too small, and that it would sink. Nothing daunted, however, the little chap rose before daylight, as is his custom, and saying, "I'm off!" took to flight. At daybreak the crane spread his wings, and, sailing majestically along, got about halfway across, when he met the hummingbird struggling in the water. The latter had made a gallant attempt, but could not of course make headway against the wind. The crane picked him up and placed him on the back of his own thighs, which stuck out behind. Now, this position was all very well for the little hummingbird so long as no accident occurred, but when the crane commenced to relieve himself, the hummingbird's face got dirtied, and he thus found himself forced to take to the wing again, with the result that, reaching Nibo-yuni first, he waited for his big friend, who arrived shortly. He now told the p. 336 crane to remain where he was, while he would visit the tobacco field; he was small, could fly swiftly, and no one would see him stealing the tobacco seed. While carrying out his design, the watch-woman tried to shoot him, but he was too smart for her, and darting quickly from flower to flower, soon collected as much seed as he required, and returned to the crane. "Friend," said he, "let us get home now," and suiting the action to the word the little creature started ahead, and now with the wind behind him, reached home first without mishap. Here he delivered the seed to the crane's master, and the latter handed it to his brother, telling him to plant it. When planted it grew very quickly, and when the leaves were fully grown, the brother showed him how to cure the tobacco. The brother also sent him to search for bark to suit the leaf [i. e. to make the cigarette], and he brought the winnamóru, which was just what was required. He next sent him for the hebu-mataro [rattle] and he brought gourds of all sizes, but at last he returned with a calabash that he had picked from off the east side of the tree; this was the very thing. The bereaved father thereupon started "singing" with the rattle, and his son and the other two lads came in answer; they were three Spirits now, and all three addressing him as father, asked for tobacco, with which he supplied them. It is these same three Tobacco Spirits, Kurusiwari, Matura-wari, and Káwai-wari, who always answer when called by the piai's rattle, and as a matter of fact it was the poor bereaved father who came to be the first piai, all through his great grief at losing his child, and longing so much to see him once more.1

296A.* KOMATARI, THE FIRST MEDICINE-MAN (W)

Komatari wanted some tobacco, but as there was none about, he searched for it. He had heard of its growing on an island out at sea, so he went down to the shore, where he came across a house with a man inside. Approaching him, Komatari said: "I am poor, and want tobacco. I hear you have it growing on an island. Could you get me some plants?" While thus engaged in conversation, the hummingbird came along, and said, "Hullo! What are you two talking about?" "Tobacco: we want tobacco," they replied. "Oh, is that all?" the little bird said; "why, I'll go and fetch some for you. I shall be making a start before the morning, and you can expect me back just as the sun begins to turn that way" [pointing in a direction which would indicate about an hour after midday]. The hummingbird kept his word, and returned as promised, but when the house-master saw what he had brought back, he said, "Why, that is no tobacco leaf: it is only the tobacco flower," and, turning to Komatari, he said, "I will go myself." The house-master started next morning for the same island, telling Komatari to expect him back as soon as the hummingbird, that is, shortly after midday. But as a matter of fact, he never returned until the following morning. The cause of the delay was that so many people were watching the tobacco that he had to wait for nightfall before he could steal the leaves. However, giving Komatari some of the seed, he told him to go down to the waterside, where he would find his corial, and if he looked inside he would see two or three tobacco leaves, which he might take. Komatari did as directed, but instead of two or three leaves he found the whole corial full of them. He helped himself to as many as would fill a quake and went home. Before taking his departure, however, the house-master said: "I have a name, but will not mention it: when you know all about Piai [i. e. 'Medicine'] you will be able to find it out for yourself." At last Komatari reached home, and naturally all his friends came to pay him a visit, to get some of the tobacco; but he was shrewd, kept the tobacco under the roof [i. e. hanging up to dry in the ordinary manner] in charge of the marabuntas [wasps], left home very early of a morning, and only returned late, so as not to be at home when anybody called. But at last a visitor p. 337 came and made a very long stay purposely. They thus met, Komatari gave him three leaves, and sent him away. Next day, another man paid him a visit, but Komatari had already left, and only marabuntas were there—many marabuntas, all of different kinds. The visitor went home, and, taking some fish with him, returned to Komatari's place and asked the marabuntas to let him have some tobacco, at the same time showing them his fish and saying, "Look! this is the payment." And so, while the marabuntas all swarmed down upon the fish, the man climbed up, got what tobacco he wanted, and cleared out. When Komatari got home, he also got up under the roof where the tobacco was stored, but found much of it missing, so he placed what was left elsewhere, and drove away all the marabuntas except one particular kind, a black variety, the oro [ = yiseri of the Arawaks], which he made his watchmen. Starting now on his field, he cut it day after day, and after burning it, at last planted his tobacco. When he saw that it was beginning to thrive, he built a piai-house, and going round his field, looked out for a calabash tree; he found one full of gourds. He took one, but on turning round, he saw a Hebu, who, after asking whether it belonged to him and getting "Yes" for an answer, said: "All right. So long as the calabash is yours, you may have the whole tree. I have a name, but will not tell it you. I want to see whether you learn the piai business well. If you do, you will be able to find it out for yourself." On reaching home with the calabash, Komatari started cleaning it out. When cleaned, another Hebu came along and asked him what he intended doing with it, but Komatari would not tell him. You see this particular Hebu was the one who comes to kill people and so was afraid of the power of the maraka [rattle], which is made from this very calabash. After scooping out and cleaning the calabash, Komatari went into the bush and, traveling along, came upon a creek with swiftly-flowing water: it was here that he cut the timber from out of which he next shaped the handle for the rattle and cut the sticks to make his special fire with.1 Returning home once more, he fastened the handle in the gourd, but was not satisfied with the result: the rattle did not look as it should. So he hung it up on the beam of his piai-house, and went once more into the bush, where he again met the killing Hebu, who repeated his question as to what Komatari intended doing with the rattle, but, as before, the latter would not tell him. Passing along, and hearing a noise as of many people talking, Komatari proceeded in the direction whence the sound came, and found a number of Hebus fastening various parrot feathers into cotton-twine. How pretty this ornament would look tied on his calabash left hanging up at home, was Komatari's first thought when he saw what they were doing. On asking, the ornament was given him. The Hebu who gave it to him said: "I have a name, but I will not tell it to you. You can find it out for yourself, if you should ever become a good piai-man." Komatari next asked him for another kind of cotton-plait, with feathers different from those on the one mentioned, to wear as a hat,2 but the Hebu said he had none, though he would get it at the next house. So Komatari went to the next house, saw the Hebu house-master, asked for the cotton-plait for the hat, and in the same manner as before, this Hebu also said to him: "I have a name, but I will not tell it to you. You must find it out for yourself when you are a medicine-man." Komatari went home now, and arranged the feathered cotton on top of the calabash, when who should put in an appearance again but the killing Hebu. When he again asked Komatari what he intended doing with the calabash, the latter refused to tell him, as before. But Komatari was not satisfied even now, because when he shook the gourd it did not rattle. As yet it had no stones in it. So Komatari went into the bush again, and followed creek after creek, and at last came to a big river. There he met another Hebu, who got the proper stones that were wanted. When he had given them to Komatari, he said, like the others: "I have a name, but p. 338 I will not tell it to you. You must find it out for yourself when you are a medicine-man." Komatari again made his way home and put the stones into the calabash. Just as he was finishing the work the killing Hebu again appeared, asking him as before, what he intended doing with the calabash. The answer was, "This is to kill you with, and to prevent you killing other people," and as Komatari shook the calabash, which was now a finished maraka rattle, the Hebu began to tremble and stagger and almost fell, but he managed to pick himself up and get away just in the nick of time. He ran to his Aijamo [head-man, chief] and said: "There is a man who has an object with which he nearly killed me and I must get my payment [i. e. my revenge]. I am going back to kill him." "All right!" said the Aijamo, "I will go with you." So they went together, and brought sickness to a friend and neighbor of Komatari's; for they were afraid of attacking Komatari himself. However, his sick friend sent for him. Komatari went, and played the maraka on him, and took out his sickness. So the killing Hebu made another man ill, but Komatari took the disease out of him also. The Hebu next afflicted a third victim, and again Komatari was victorious. But when he attacked a fourth one, Komatari was out hunting. When he returned, the poor fellow was in a bad enough condition: so strong did the sickness come, that Komatari could not cure him—he had "stood too long." The killing Hebu then explained to Komatari that it would always be thus: some patients he (Komatari) could save, and other patients he could not. Of course Komatari had been able to find out the names of all the Hebus that had lent him assistance in the manufacture of his maraka, and it is to these different Hebus whom the present-day medicine-men are said to "sing" and call on when they cure the sick. For instance the name of the Hebu that procured the tobacco seeds for Komatari was Wau-uno [ = Arawak Anura], "the white crane."

297.* The apprenticeship of the medicine-man in the olden days was very far from being the proverbial bed of roses. Among other tests, he had for many months to practise self-denial, and submit under a stinted diet to the prohibition of what were to him accustomed luxuries. He had to satisfy his teacher in his knowledge of the instincts and habits of animals, in the properties of plants, and the seasons for flowering and bearing, for the piai man was often consulted as to when and where game was to be found, and he was more than often correct in his surmises. He also had to know of the grouping of the stars into constellations, and the legends connected not only with them, but with his own tribe. He had likewise to be conversant with the media for the invocation of the Spirits, as chants and recitatives, and also to be able to imitate animal and human voices. He had to submit to a chance of death by drinking a decoction of tobacco in repeated and increasing doses, and to have his eyes washed with the infusion of hiari leaves (Sect. 169); he slowly recovered, with a confused mind, believing that in his trance, the effect of narcotics and a distempered mind, he was admitted into the company of the Spirits, that he conversed with them, and was by themselves consecrated to the office of piai priest-doctor (Da, 285). Bancroft (316) says that the novitiate "is dosed with the juice of tobacco till it no longer operates as an emetic." Sometimes, as among the Oyambis on the Oyapock River in French Guiana, other things were mixed with the tobacco, for example, a plant called p. 339 quinquiva, as well as certain of the drippings from an exposed dead body (Cr, 158). For the same colony Fathers Grillet and Bechamel (GB, 48) record that the medicine-men proffer neither physic nor divination "till they have made divers experiments, one of which is so dangerous that it often makes them burst. They stamp the green leaves of tobacco and squeeze out the juice of it, of which they drink the quantity of a large glassful, etc.; so that none but those who are of a very robust constitution, who try this practice upon themselves, escape with their lives." Brett (Br, 362) also testifies to the severity of the ordeal, for after the novice has been reduced to the deathlike state of sickness to which the fasting coupled with the drinking of tobacco-water has brought him—

His death is loudly proclaimed, and his countrymen called to witness his state. Recovery is slow, and about the tenth day he comes forth from the sacred hut in a most emaciated condition. For ten months after the new sorcerer must abstain from the flesh of birds and beasts, and only the smallest kinds of fish are allowed him. Even cassava bread is to be eaten sparingly, and intoxicating drinks avoided during that period. Meats and food not indigenous to the country are especially tabooed. . . . McClintock states that the "above rules are common to the Caribs as well as the Waraus, but that the former are allowed during their period of abstinence to take a little meat—the flesh of the Acouri. . . . The Akawoios differ in some respects from the other tribes, inasmuch as not less than four, and frequently more, become M. D.'s at the same time."

Gumilla (II, 25), on the Orinoco speaks of the apprenticeship of the Piache in the following terms:

In the forest of Casiabo, there was a medicine-man named Tulujay, so celebrated that Indians flocked to him from all quarters, but they did not all come to learn, nor subject themselves to his teaching, because this cost them very dear. For besides adequate payment, he imposes such a rigorous 40-day fast on them, that few dare to undertake it: of those that do, the majority leave the Master weakened with the fasting: he who completes it is made to swallow, without chewing, three pills, manufactured of different herbs, of the size of a cherry-stone. These pills are said to be an antidote for every kind of poison, and so render the disciple secure from all his rivals and enemies. The credulity of the Indians is so simple that none of them will meddle with any individuals so treated (curados).

Most of the above accounts are concerned mainly with the drinking of the tobacco, an ordeal to which the old-time missionaries and travelers seem chiefly to have devoted their attention. Though it would have been of course more or less practised beforehand, the tobacco ordeal in its entirety was reserved for the grand day when the public installation took place. During his course of training, in addition to his other instruction, the apprentice was taught to suffer the pangs of hunger and thirst, and to experience the martyrdom of pain without complaint or murmur. To teach him the latter, he was either bitten with ants or cut on various portions of the body. Among the Islanders "his body is scraped with acouri teeth" (BBR, 236). The ants were fixed into the interstices of plaited diamond-shaped p. 340 mats or girdles and these were held or tied on the neck, breast, stomach, or legs (WJ, 91). In some cases, during their period of probationership, the prospective medicine-men must not come into contact with Europeans, as this would destroy forever their influence over the spirit world (ScR, I, 423). West of the Orinoco, "they submitted to a seclusion of two years in caverns, situated in the deepest recesses of the forests. During this period they ate no animal food; they saw no person, not even their parents. The old Piaches or doctors went and instructed them during the night" (FD, 50). Magic stones are alleged to be placed in the novitiate's head (KG, II, 154). Crévaux, among the Roucouyennes of the Yary River, French Guiana, speaks of the "many years of probationership" (Cr, 117). "Takes some years: the novice returns more like a skeleton than a man among his people" (ScR, I, 423-4). The only account of a public installation of the would-be piai, actually described as such, comes from Cayenne:

At the public installation to which the neighboring piais are invited, the aspirant has to swallow at one draught a calabash containing about two pints of tobacco-juice. Most often he falls into a swoon, whereupon he is carried to his hammock: if he does not vomit directly after taking this powerful emetic, he dies, or at least he is seized with horrible convulsions and breaks out into cold sweats, etc., which all tend to bring him to the grave. But if he survives, he is acclaimed Piai. [PBa, 211.]

In the Island practices, the novitiate is made to drink tobacco-juice until he faints, and, when they say that his Spirit has gone to the Chemeen, they rub his body with gum, and cover it with feathers to allow him to fly to the Chemeen (BBR, 235). Among the Pomeroon District Arawaks and Warraus it would seem that the aspirant wore a special cotton headdress at the time of installation. Pitou mentions the piai installation as taking place on the night before the marriages (LAP, II, 266).

298.* Mention has already been made (Sect. 297) of the knowledge, of which the medicine-man had to give proof, concerning the instincts, habits, etc., of animals. Seated on his professional stool, with maraka in hand, he might be observed studying where game is to be found by the morrow's daybreak. He lights up his fire, and igniting some tobacco, he invites by invocation the spirits of the game he desires (Sect. 116). In his enthusiasm he speaks to them and answers for them in their supposed peculiar tones, modulated as in ventriloquy; for he believes that, being possessed, they answer through him, he being at the same time the humble earnest inquirer and the sufficient aswerer of his own inquiries (Da, 287). This belief in the interdependence of the priesthood and animal life is well illustrated in an example (Ti, II, 1883, p. 348) given by McClintock: "I had an Accawoi huntsman who was a sorcerer (peaiman) and considered that he had certain birds and animals so completely under his control that p. 341 no inducement would have tempted him to kill any of them; among them were powis . . . maroodies, and the Arua tiger. . . . The latter he always told he could put his hand upon any time he went out."

Another apt illustration is furnished by Schomburgk: "In our peregrinations in the savannahs we frequently met with the nests, of wild bees. They belonged to a species which the Makusi Indians called wampang; the Wapisiana camuiba. The hives or nests are generally fixed to branches of trees, and are from 2 to 3 feet in length. . . . It stings severely; and in order to secure nests, the Indians kindle fires under them, when the insects abandon their fabrics en masse. I have, however, seen an Indian who was the conjurer or piaiman of his tribe, merely approach the nest, and knocking with his fingers against it, drive out all the bees without a single one injuring him. I noticed him drawing his fingers under the pits of his arms before he knocked against the hive" (ScT, 40). The piai system made a secret art of hunting; from the priest-doctor the hunters learned to hunt for the particular game they required, and received at his hands charms—maklar and bina—to insure their success (Da, 251). Among the Indians of the Uaupes River, the piais are believed to have power to destroy dogs or game and to make the fish leave a river (ARW, 347). The medicine-man furthermore could transform himself into an animal (Sect. 154); if his wife becomes pregnant she may bear him a tiger, an animal into which he himself may be transformed at death (KG, II, 154).

299.* Certainly among many of the tribes the "doctors" were believed to be endowed with such power over their own spirits as to render themselves invisible. At a Makusi village on the Karakarang River, a branch of the Cotinga, Barrington Brown (Bro, 119) was told that many of their people had gone to Roraima to see an Indian sorcerer there who had the power of making himself invisible at will. At Mora village, on the upper Rupununi, the same traveler (Bro, 139) explains how the piai's absence for the night was unavoidable, owing to his having to go up among the mountains to roam about for the night, while his good spirit remained in one of the houses to cure a sick man.

Not only could the medicine-man invoke Spirits generally, as well as those of particular birds and beasts, but he could also play tricks with his own and other Indians' Spirits. Thus, im Thurn (339): "He is able to call to him and question the spirit of any sleeping Indian of his own tribe, so that if an Indian wishes to know what an absent friend is doing, he has only to employ the piai-man to summon and question the spirit of the far-away Indian. Or the piai-man may send his own spirit, his body remaining present, to get the required information."

300.* The piai's reputation as an interpreter of dreams was second to none: he was both dreamer and seer (Sect. 298), but this is only what p. 342 might have been expected, considering the powers he possessed over other people's Spirits (Sect. 299), and dreams are really but people's Spirits (Sect. 86).

A certain man had two wives, but unfortunately they did not agree, the elder being jealous of the younger. At last there was so much contention, that the husband was obliged to send the younger one away, and she took her baby with her. He had no bad mind toward her, but he could not stand the continual quarreling. When taking her departure, he gave her a sharp knife with which to protect herself on the road. The poor woman wandered on until nightfall, when she came upon a fine ite [Mauritia] palm; cutting a forked stick, she planted it against the tree, and climbed on it. Taking the youngest as-yet-unopened leaf, she spread it out and made a sort of temporary basket of it, into which she coiled herself together with her baby, and there she tried to sleep. Now, upon this particular palm, the fruit was plentiful—some seven or eight bunches—and around the stalk of each bunch she had taken the precaution of cutting a little ring, so that with the slightest touch, any bunch would fall to the ground. Somehow or other, the unhappy mother could not sleep, and late in the night she heard the growling of the tigers who had been attracted by her scent. One of these brutes climbed the palm and jumped on one of the fruits, but no sooner had he touched it than it gave way and he fell with a crash into the very midst of his fellows below who, believing him to be the woman they were in search of, promptly tore him to pieces. Another tiger made a similar attempt, climbed the tree, jumped on the fruit, and ended in the same disastrous manner. And so with a third, fourth, fifth, and sixth tiger—all were similarly destroyed. By this time the dawn had broken, and the carcasses were left rotting at the bottom of the tree. What a sight for the terrified mother nestling up above! She could see all the tigers lying still and quiet, but was afraid to come down lest they might still be alive. She therefore waited a little and when, after the rising of the sun, she recognized a wasp settling on each of their protruded tongues, she knew that the tigers must all be dead and could now do her no harm. As soon as she got down she continued her journey, and wandering along all day, she arrived about nightfall at a big manicole tree, which she climbed, with the baby fastened on her back. Tigers were likewise very prevalent here, and scenting her presence, they started digging around the roots with the result that by and by, the tree fell with a crash, but fortunately into an immense spider-web, where its living freight became stuck. Now the woman's father was a celebrated piai, and while the first night's occurrences were taking place, he was dreaming all about her and the tigers. Next morning he started to search and came upon her while resting in the spider-web. It was owing to the baby making water that he had cause to look up and discover his daughter. By daylight he had shot the tigers that were prowling around, and then helped down the woman and his grandchild. Both daughter and father cried; the former had been so strongly punished, the latter was so glad to have her home again.

301.* Among other duties that the medicine-men might be called on to perform was to fix the time most propitious for the people to attack their enemies (HWB, 244). They were supposed to be gifted with the power of prophecy: they foretold the issue of battles (BBR, 234), whether there would be war or peace; similarly, they could prophesy as to the crops—whether these would prove scanty or abundant (FD, 51).

302.* The Pomeroon Arawaks appear to credit the piai with being able to influence the Yawahus in bringing the as-yet-unborn babes to the mothers (Sect. 284A). In some districts, as on the Berbice, the piais were said to be professional poisoners, but it must be remembered that the charge of poisoning was one made against an Arawaks as a habit (Da, 16). Among the wurali-poison-making tribes, for example, the Makusis, Bernau's statement (Be, 36) that the "conjurers alone are conversant with the art of compounding it" does not seem to be borne out by the facts. At one place on the Orinoco, as already stated (Sect. 297), the sorcerers were alleged to be rendered poison-proof (G, II, 25). Waterton's statement (W, 223) that "he is an enchanter: he finds out things lost" is only a further example of the piai's supposed versatility. I remember on one occasion unconsciously giving great offence to my old doctor-friend, Bariki, now alas! gone to his long, last rest, by asking him if he knew so-and-so: he gave me a withering glance, and after a few moments, silence, said, "I know all things." Taking the hint, I subsequently invariably sought information from him by putting my question in the form of "Tell me this, or that," with the result that, pleased with my appreciation of his mental superiority, he was always ready to impart all he knew, and perhaps more.

303.* The following legend is another good example showing that there was very little that the medicine-man could not do in the natural or supernatural sphere: it is apparently a variant of the stories given in Sects. 137 and 142.

*THE MEDICINE-MAN AND THE CARRION CROWS (A)

Makanauro was a very clever medicine-man; we call such an one a semi-chichi. Setting his traps out in the bush, he was always certain of catching something, be it bird or beast. But for some little time he found to his annoyance on going to his trap, that some one had forestalled him and had stolen the meat inside. It puzzled him how this could have been done, because there were no footprints or broken bushes about, to show the advent or departure of any stranger. So he one day climbed a tree in close proximity to one of his traps, and watched from his elevated position. He saw some game caught in the trap and by and by a black Carrion-crow [Cathartes burrovianus] came swooping down, and try to cut it up with a knife, so as to remove it the easier. The Crow's knife, however, was too blunt, so he flew away and fetched the Vulture [Sarcorhamphus papa], who brought a sharper knife with him, and cut up all the meat nicely. And then a lot more Carrion-crows came down, and between them they cleared every particle of the meat away, leaving the trap as empty as before. Makanauro watched all this quietly from under cover of the tree branches, and on several other occasions subsequently saw them play him the same trick, the Vulture being invariably the ringleader. He made up his mind to catch this bird, and disguising himself with cotton, which he stuck all over him, including eyes, nose, and head, he laid himself down on the ground quite close to one of his traps that had game in it, and remained perfectly still. As usual, the Crow came down first, but his knife was still too blunt to cut up either Makanauro or the meat inside the p. 344 trap, and so he went, as before, to fetch the Vulture. And when the Vulture came quite close, Makanauro seized him, and held him fast; this made all the other common Crows frightened and they flew away. The bird himself thought that his captor must be a piai, because no one else could have secured him so simply. Now, I have made a mistake talking about "himself," "his," and "him," because it was a hen-bird, as Makanauro speedily found out. Indeed, she was a very fine woman, and he married her there and then. And thus they lived comfortably together for many years, all the Carrion-crows having returned to live in the vicinity as friends and companions. One day, the wife sent him for some water, and gave him a quake to bring it in. He took it down to the riverside, but couldn't "catch" any, of course, because as fast as he poured it in, it flowed out through the meshwork. He tried several times, until at last some muneri ants, noticing his extraordinary movements, asked him what he was trying to do, and when they learnt how anxious he was to oblige his wife, they offered to patch up all the interstices of the basket with "ant-bed," When they had finished the job, the quake retained the water, and Makanauro brought it home full up to the brim. On seeing this, his wife said to herself, "Yes, indeed. My husband must be a real semi-chichi to be able to bring water in a quake for me." And yet she had her doubts about the matter, so she thought she would try him a second time. She accordingly sent him to cut a field for her, but on returning each morning he found that all the timber and bushes that he had cut down the day before were growing again and thriving in their original positions. As a matter of fact, the Carrion-crows had flown to the field each night, at the bidding of the Vulture, and set up again the trees and bushes that had been felled. But poor Makanauro did not know this. All he could do was to ask the kushi ants to eat up the wood, branches and leaves, as fast as he could cut them down; these, knowing the facts of the case, made up their minds to help him, and did so. The Carrion-crows could not fight against the kushi ants, and so Makanauro managed to complete the clearing of his field. And though his wife was inclined at heart still more to believe that her husband was a medicine-man, considering the circumstances under which, as she believed, he had cut his field, she was yet in doubt about it, and determined to try him a third time. She therefore sent him to make a chair-bench for her mother-in-law; he had to carve the head at each extremity into the exact likeness of the old woman. This task she thought was practically impossible;1 and Makanauro thought so, too, because as yet he had never set eyes on his mother-in-law. However, he tried to find out, but every time he even looked in the direction of the old woman, she immediately covered her face with her hand, or turned it aside, or downward. How to make her turn her face upward so as to get a good look at it, was what puzzled him. At last he hit upon an idea. Without her knowing it, he climbed into the roof, and throwing down a centipede so as to fall "flop" into her lap, made her extend her arms and look up for a second, just as he wanted. Then starting to work, he cut up the log, trimmed it into the necessary shape, and finally carved excellent likenesses on the two heads. When completed, his wife took the bench to her mother-in-law, who laughed when she saw her two portraits; certain it is, that both women wondered greatly how Makanauro had managed to obtain a sufficiently good view to enable him to make so exact a likeness. The wife now became quite proud of her husband, and fond of him, too, because he always carried out her wishes. If she asked him to bring her some fish, he would fetch her some wrapped up in a small parcel: and when as usual she would pout her lips and hint that it was not a large quantity, he would tell her to open it, and then the fish would come tumbling out, one after the other, in immense quantities, filling the whole house [cf. Sect. 28] And he would laugh, because being a piai, he could do extraordinary things. A fine boy had long blessed their union, and the p. 345 mother was beginning to feel homesick: anxious to show off her husband and child to her own people, she told him that they must all leave his place, and go to her father's, up and beyond the clouds. And there they remained with her relations, the Carrion-crows, for many a long day. She, however, was always telling her folk what a clever man her husband was, and that whatever she asked him to do, do it he did. So these Crows asked him to perform a number of seemingly impossible feats, and not one did he fail in executing. But this only made all the Crows jealous of him, and they determined to put him to death. Makanauro, being a medicine-man, however, knew that they proposed doing so, and said, "All right. Let me get back to my place, and fetch my friends, and we will fight it out." So, taking his wife and son, he returned to his old home, and collecting all the birds in the neighborhood, he told them to prepare for the onslaught with the Carrion-crows. Now, when these arrived and saw the hosts of other birds ready to receive them, they determined to secure by stratagem a victory which they recognized they could not obtain by force. Their idea was to burn up the whole world, together with Makanauro and his friends in it. For this purpose, the Crows started fires here, there, and everywhere around, but Makanauro saw his friend the black kurri-kurri [Harpiprion cayennensis] flying high, and told all his other friends to curse her, he joining in their imprecations. This made the rain fall, and so the fires were extinguished.1 Now that his wife became angered with him for having frustrated her own people, the Crows, in their design of burning up the world in general, Makanauro left her and went his way. She then sent her son to waylay and kill him, but whether he effected this wicked design I do not know.2

304.* In some cases the piais were recognized to a greater or less extent as the guardians of the tribal traditions. Thus in the "Archivos de Indias; Patronato. Rodrigo de Navarrete: An account of the Provinces and Nations of the Aruacas" [Arawaks], written some time during the last quarter of the sixteenth century, a work quoted by Rodway, in Timehri (for 1895, p. 10), there is the following interesting reference:

These Indians have a meeting-place or school where they assemble, as in a manner for preaching. There are among them old and wise men whom they call Cemetu [compare the usual form Cemi, Semi, etc., Sect. 93]; these assemble in the houses designed for their meetings and these these old men recount the traditions and exploits of their ancestors and great men: and also narrate what those ancestors heard from their forefathers; so that in this manner they remember the most ancient events of their country and people. And, in like manner they recount or preach about events relating to the heavens, the sun, moon, and stars.

305.* The medicine-men not only gave names to the children, as with the Arawaks (Sect. 264), but under certain circumstances would change them. Thus, among this same nation, if a piai is called on to treat a sick child, and is successful in effecting a cure, he may give his little patient a new name, and thus enable it to make a fresh start in life.

306.* The chief business, however, of these doctors is centered in counteracting the evil designs of certain Spirits, Kanaima or other, p. 346 who cause disease of such a nature as to baffle the ordinary home treatment and household remedies of the average Indian, though I know of one instance in which a woman in labor was brought by her husband to seek remedial measures from one of this fraternity. The home treatment just referred to might consist in the use of ordinary herbs, vapor baths, and in other measures known to the average Indian. But occasionally, as with the Dakinis, to obtain such an herbal remedy, the piai's assistance may have to be invoked (Sect. 168B). As a matter of fact, all disease which does not respond readily to treatment is ascribed to various Spirits acting directly or indirectly, by means of thorns, pointed bones, etc., maliciously inserted into the body of the patient. When once invoked, the medicine-man is able to learn the cause of the trouble, and how to combat its effects.

307.* Disease or death is not a "natural" phenomenon, so to speak, but is usually due to one of two agencies. It may be the work of some Spirit, perpetrated either judicially or of mere malice, as some affirm, or through the importunity of a votary. An evil Spirit, one who causes an evil, might send an animal to bite or sting a person, or cause a tree to fall upon him, his ax to cut him, water to drown him, or some other calamity (Da, 289). Now, except through the agency of the piai, the influence of this Spirit causing the evil can not usually be counteracted. Berman alone for the Mainland makes the statement, which I must regard as confirmed by the practice of a similar custom on the Islands, that "when sickness assails them, they [laymen, Sect. 89] present a propitiation to the Evil Spirit, consisting of a piece of the flesh of any quadruped. If recovery follows, they suppose the Evil Spirit to have regarded and accepted the offering," but if no recovery, the conjurer is called in, etc. (Be, 51-54). The piais are undoubtedly believed to have the power of influencing the Spirits not only in removing the causes of the disease which they (the Spirits) have inflicted, but also in sending sickness elsewhere (Sect. 319) In the spring of 1907 the Ojanas (Cayenne) suffered from an epidemic of bronchitis, or "galloping consumption," from which many died; this was ascribed to the piais (Go, 14). It is possible, however, that the medicine-men, independently of Spirits, and certain old people, can inflict sickness on folks at a distance; for instance, the Apaläi Indians of the upper Parou, Cayenne, when they can not subdue their sicknesses revenge themselves by sending an evil charm to a woman (Sect. 319) of the neighboring tribe (Cr, 299). It is not at an uncommon for one tribe to put the blame of some real or imagined ill on the shoulders of another. For example, the Wapisianas consider the Makusis the most dangerous poisoners and Kanaimas—every illness is ascribed by them to the wickedness of the Makusis (ScR, II, 387). Similarly, on the Tiquie River (Rio Negro) the Makus p. 347 are blamed for everything (KG, I, 270). There is a certain skin disease, believed to be a vitiligo, which the Piapocos of the lower Guaviar (Orinoco River) call sero: it is always contracted by drinking the yocuto (couac mixed with water) of an enemy affected with this trouble, who has mixed in the brew a few drops of his blood (Cr, 527). Death and other evils may be due also to some human enemy more or less disguised, modified, or influenced by a peculiarly terrible Spirit known as Kanaima, against whose machinations the power of the piai avails nothing. To this belief in Kanaima I propose devoting a separate chapter (Sect. 320).

308.* In the Pomeroon District, the present-day Arawak procedure of the piai, for the treatment of disease, is as follows: Suppose the patient visits the "doctor," the latter will sling the sufferer's hammock in the special out-house already mentioned. In those cases in which the person is too ill to bear removal, the doctor will visit him, and there erect a closely plaited conical-shaped cage of manicole leaves, with a low door only just large enough to crawl in and out by. Nothing further can be done now until the sun sets, but as soon after sundown as convenient the medicine-man will start a new fire, by twirling one stick upon another. The fire once kindled, he rolls tobacco to make the usual Indian cigarette, and proceeds to examine the patient. He then asks what the pain is like, and where it is—as, in stomach, head, chest,—and talks to his kickshaws, especially the manikin, or doll, to learn whether the patient is going to be cured. The method of employment of this doll has already been given (Sect. 290). Seated on his special chair, the doctor next lights and smokes his cigarette, and finally rubs his hands with haiawa wax. This done, he proceeds to massage the painful spot, and smokes on it through his hands placed funnel-wise. This part of the treatment may be viewed by the public, there being nothing secret or mysterious about it, and may of itself effect a cure, in which case, as the Creoles would say, "Story done." With the next procedure, however, provided the illness prove stubborn, the females are all sent away from the place, men have to keep at a respectful distance, quiet must reign, and all lights have to be extinguished. The alleged reason for putting out the fires is that the various Spirits whom he is now about to invoke may not be afraid to come. (If the treatment is being carried out at the patient's residence, the medicine-man will crawl into the cage when the invocation takes place.) In the meantime, the medicine-man cleans and polishes his maraka, which he pieces together, and ties the feathers carefully on, smoking on it all the while: he sings and shakes his rattle. Leaving his bench, he touches the painful spot or spots with the maraka, circling it in the air, smoking and singing all the while, altering his voice from bass to alto and vice-versa according to the voice of the Spirit which is presumed p. 348 to be conversing with him. Apparently two voices are often heard. When it is remembered that the Spirit may be anything from a tiger to a powis, even another piai, the various modulations of voice and speech which he has been trained to reproduce can be better imagined than described. He does not know beforehand which one has wrought the mischief; hence he has to invite and interrogate each one. This manner of invocation, according to the fee given, may continue until two or three in the morning—there is a limit to the doctor's powers and endurance—when all the kickshaws will be put away in the specially constructed pegall. Our medicine-man, seated on his divining stool, will proceed to smoke and dream, and in his dream he will discover at whose instigation the sickness has been sent, and whether the illness itself is due to a dead person's Spirit (as a Bush Spirit), to a living one's Spirit (a Kanaima), or to the Oriyu, or Water Spirit. At the same time he also learns the mode of cure. Next morning he will retail this information either to the patient or to his friends, as soon as he is paid something over and above the fee (as cloth, beads, money), which he has already received. The cure may be such as can then and there be carried out, as the extraction of the evil by suction, or the disease may prove of so serious a nature that it is a matter for the Spirits alone to deal with. At any rate the medicine-man then gives careful directions as to how the patient and his relatives are to be fed—with bird, fish, or otherwise, as the case may be—but there is always the stipulation that whatever is ordered (a) must never be added to, or taken away from, for example, no salt, peppers, seasoning, etc., and no "trimming off;" (b) must be cooked with the doctor's own fire, or with another specially made for the purpose by means of two pieces of stick, care being taken in both cases that it is not touched by a stranger; (c) must not be allowed to boil over the edge of the pot. If during the course of the day the patient should not improve, the doctor will repeat the treatment the same night—smoking, singing, and dreaming—but on this occasion, addressing the Spirit which has caused the mischief, he implores it if possible to restore the health which it has impaired. He may even repeat all this the third night if the patient's grave condition warrants so doing, and he is paid an adequate fee. At any rate, when he finally completes the treatment the doctor invariably tells the patient, unless the latter is actually moribund, that he will recover, but that both he and his family must be very careful as to the foods prescribed, for should the sufferer unfortunately die it is always because one or other of the stipulations regarding diet has not been properly obeyed. When, during the course of the treatment, rain happens to fall, the proceedings are immediately postponed to the following evening.

309.* Among the Pomeroon Caribs I have been present on several occasions on the Manawarin River at the procedure adopted by a piai to affect a cure. It has always been at night, with the doctor seated in a small temporary cone-shaped structure roughly made of manicole leaves, and the rattle brought into requisition. Operations invariably commenced with the invocation of four particular Spirits by "singing" to them, each with a different song, by tobacco smoke, and by shaking the maraka. As a matter of fact the medico is said to call up only the first Spirit; the latter, however, invokes the second, and so on. The names of these four Spirits, in the order in which they are summoned, are Mawari (Sect. 122), Makai-abáni, Iakai-a, and Aturaróni. All except the second live somewhere in the bush, but they come when summoned by the rattle. Makai-abáni, on the other hand, remains in the maraka, coming out only when shaken, and then he envelops himself in the tobacco-smoke. All these four are good Spirits and friends of the piai; they are male and female, like people, and come from the bodies of old-time medicine-men; they tell the celebrant whether the disease from which the sick man is suffering has been sent by another Spirit or by another piai at the instigation of some enemy. The three evil Spirits who send sickness, ill-luck, and other calamities to mankind, belong to Cloud-land, and to Water; Kwamaraka lives in the sky below the clouds and is something like a "gaulding" bird (Pilerodius); Tokoroi-mo has his home below the clouds, and resembles the "doraquarra" bird (Odontophorus); while Oko-yumo is the "water-mamma" (Sect. 177). These three have a master, called No-séno, who lives somewhere above the clouds; he is a man, a very bad one, is always for killing somebody, and is his own master. But to return. If the disease has been sent by one or other of these bad Spirits, the piai gets Mawari to take it far, far away, away to the Orinoco River; but if by another piai, the present celebrant will send it back to him, and woe betide the latter if he is not smart enough to avoid it, for unless he takes very great care he is sure to die from it. Should, however, the sickness prove stubborn, "Tiger" is finally called on; directly his voice is heard the disease comes out to be speedily devoured by him. But if Tiger should prove unsuccessful, nothing now can possibly save the patient.

310.* The Galibi piai of French Guiana practised similar methods, according to the accounts left us by Barrere: After placing the maraka below the patient's hammock, the piai starts sucking at those parts of the sick person's body where the pains are greatest, afterward passing both hands over the patient; he then strikes his hands together and blows on each palm (Sect. 85) so as to drive away the "Devil" [spirit] that has attached itself there (Sect. 74); the piai will sometimes pinch up pieces of his own skin, and thus extracting corpulency (embonpoint) and good health, will apply these in handsful to the patient while making the passes over him. p. 350 These Indians also employed the little hut specially constructed in the karbet, in which, after all the lights have been extinguished, the medicine-men "sings" and shakes the rattle. He often comes out of his little cabin and would pretend that it is the Devil [Spirit] that has got out. He will then run right round the karbet and tug at the hammocks in which the Indians are lying. He sometimes says that he is going up into the skies, but will soon return, and he will then mimic the distant voice, etc. (PBa, 213-215).

311.* In remote parts [of French Guiana] and toward the sources of the River Oyapok, the Indians [? Oyampis] practise another method, with the figure of a Devil [Spirit] made of a very soft and resonant wood. This statue, which is three or four feet high, looks frightful with its long tail (queue) and big claws with which they provide it. They call it Anaan-tanha (literally, Devil-figure). After having blown on the sick person, the piais carry the statue out of the hut. There they talk to it, and thrash it unmercifully with sticks, so as to force the Devil [Spirit], in spite of itself, to leave the sick person. These exorcisms are carried out at night, after the fires have been extinguished (PBa, 216). Very interesting in this connection is the maize-straw manikin, found by Crévaux, among the Apaläi Indians of Cayenne (Cr, 301), which may have been employed for a similar purpose; it represented a warrior ready to let fly an arrow, fixed on two sticks arranged crosswise like a gallows.

312.* It is not always necessary, however, to use the maraka, it being quite possible to invoke the Spirits with a couple of bundles of leaves. Thus, Schomburgk gives the following account of a Makusi performance at Nappi, on the Canuku Mountains:

The old man came into my hut with two bundles of leaves in his hands, and with them he drove out the other occupants. He then put out all the fires, sat near my hammock on the ground, which he whipped with the bundles, and started howling, only now and again broken by short pauses. After this had gone on for a quarter of an hour, I recognized a second voice by the side of my hammock, and question and answer went on between the two. The conversations with the evil spirits are unintelligible even to the Indians: it was next morning that the piai took care to make them aware of its contents. After the double conversation was finished, the magician placed himself at the head-end of my hammock, howled close to my forehead and, after lighting a cigar, blew strong clouds of tobacco-smoke into my face which almost suffocated me, and pressed the bundle of leaves (which I recognized by the smell as tobacco leaves) onto my forehead. This went on for quite half an hour and got me into a good sweat: at last his voice failed him, and he left the hut. He did not use the maraka. [ScR II, 145-146.]

313.* Westward of the Guianas a particular kind of wood apparently played the same rôle as the rattle or the leaf-bundle, if we accept the statement of Depons in his description of the Captain Generalship of Caracas:

The practice of these professors of the healing art consisted in licking and sucking the affected part, in order, according to them, to eliminate the peccant humour. p. 351 When the fever or pain increased, suction of the joints, as well as friction over all the body with the hand, was employed. During the performance of this operation, some unintelligible words were pronounced, with a loud voice, commanding the evil spirits to depart out of the patient's body. If the malady did not readily yield, the Piache or physician had recourse to a particular kind of wood, known to himself alone, with which he rubbed the breast, throat, and mouth of the patient; a practice which seldom failed to produce sickness and vomiting. In the meantime the Piache on his side uttered dreadful exclamations, howled, shook, and made a thousand contortions with his body. If the sick person recovered, everything contained in the house was given to the Piache; if he died, the fault was imputed to Destiny, never to the physician. [FD, 50.]

314.* Among the Island Carib Indians the piai procedure was of the simplest kind:

They say that the Chemeen [Sect. 90 et seq.] always comes on scenting the odor of this incense [tobacco] and, being interrogated, he answers with a clear voice, but sounding as from a distance. The sorcerer then approaches the sick person repeatedly, feels, presses, and manipulates the suffering part, always blowing on it, and extracts something from it, or rather appears to extract, some thorns, or small pieces of cassava, wood, or bones, making the sick person believe that this was the sole cause of the pain. Very often he sucks the painful part, and immediately goes out of the house to vomit what he calls the poison. [BBR, 234.]

The following are further particulars of the Island practices as reported by Rochefort and Poincy:

The Boye . . . consults his Familiar Spirit who tells him that it is the [Familiar] Spirit of such an one who has done it [who has brought the mischief] [RoP, 473]. . . . Then the devil [Familiar Spirit] whom he has invoked . . . violently shakes the ridge of the roof, or with some other noise immediately appears, and replies distinctly to all the questions asked by the Boye [ibid., 563]. . . . If the devil assures him that the illness is not mortal, both the Boye and the accompanying phantom approach the sick person to assure him that he will soon be cured: and to encourage him in this hope they touch gently the most painiul parts of his body, and having pressed them a little pretend to extract from them thorns, broken bones, splinters of wood and stones which these wretched doctors say were the cause of the ill. They also moisten with their breath the weak spot and having repeatedly sucked it, they persuade the patient that by this means they have extracted the poison which was in his body and kept it in languor. They finally rub the sick person's body with junipa fruit. . . . But if the Boye has learnt from the communication which he has had with his demon that the sickness is a fatal one, he contents himself with consoling the sick person by the statement that this God, or rather to say, his Familiar Devil, having pity on him, wishes to take him into his company, so as to be freed from all his infirmities. [RoP, 564.]