Sacred Texts Egypt Index Previous Next

The Rosetta Stone, by E.A.W. Budge, [1893], at sacred-texts.com

Greek writers upon Egyptian hieroglyphics.To Hecataeus of Miletus, 1 who visited Egypt between B.C. 513-501, we owe, through Herodotus, much knowledge of Egypt, and he must be considered the earliest Greek writer upon Egypt. Hellanitus of Mytilene, B.C. 478-393, shows in his Αιγυπτιακὰ that he has some accurate knowledge of the meaning of some hieroglyphic words. 2 Democritus wrote upon the hieroglyphics of Meroë, 3 but this work is lost. Herodotus says that the Egyptians used two quite different kinds of writing, one of which is called sacred (hieroglyphic), the other common 4 (demotic). Diodorus says that the Ethiopian letters are called by the Egyptians "hieroglyphics." 5 Strabo, speaking of the obelisks at Thebes, says that there are inscriptions upon them which proclaim the riches and power of their kings, and that their rule extends even to Scythia, Bactria, and India. 6 Chaeremon of Naucratis, who lived in the first half of the first century after Christ, 7 and who must be an entirely different person from Chaeremon the companion of Aelius Gallus (B.C. 25),

Greek writers upon Egyptian hieroglyphics.derided by Strabo, 1 and charged with lying by Josephus, 2 wrote a work on Egyptian hieroglyphics 3, περὶ τῶν ἱερῶν γραμμάτων, which has been lost. He appears to have been attached to the great library of Alexandria, and as he was a "sacred scribe," it may therefore be assumed that he had access to many important works on hieroglyphics, and that he understood them. He is mentioned by Eusebius 4 as Χαιρήμων ὁ ἱερογραμματεύς, and by Suidas, 5 but neither of these writers gives any information as to the contents of his work on hieroglyphics, and we should have no idea of the manner of work it was but for the extract preserved by John Tzetzes on Egyptian hieroglyphics.John Tzetzes (Τζέτζης, born about AḌ. 1110, died after AḌ. 1180). Tzetzes was a man of considerable learning and literary activity, and his works 6 have value on account of the lost books which are quoted in them. In his Chiliades 7 (Bk. V., line 395) he speaks of ὁ Αἰγύπτιος ἱερογραμματεὺς Χαιρήμων, and refers to Chaeremon's διδάγματα τῶν ἱερῶν γραμμάτων. In his Exegesis of Homer's Iliad he gives an extract from the work itself, and we are able to see at once that it was written by one who was able to give his information at first hand. This interesting extract was first brought to the notice of the world by the late Dr. Birch, who published a paper on it in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature, Vol. III., second series, 1850, pp. 385-396. In it he quoted the Greek text of the extract, from the edition of Tzetzes' Exegesis, first published by Hermann, 8 and added remarks and hieroglyphic characters illustrative of it, together with the scholia of Tzetzes, the text of which he emended in places. As this extract is so important for the history of

the study of hieroglyphics, it is given here, together with the scholia on it, from the excellent edition of the Greek text, by Lud. Bachmann, Scholia in Homeri Iliadem, Lipsiae, 1835, pp. 823, § 97 and 838, with an English translation.

Extract from Tzetzes' work on the Iliad

Translation of the extract."Now, Homer says this as he was accurately instructed in all learning by means of the symbolic Ethiopian characters. For the Ethiopians do not use alphabetic characters, but depict animals of all sorts instead, and limbs and members of these animals; for the sacred scribes in former times desired

to conceal their opinion about the nature of the gods, and therefore handed all this down to their own children by allegorical methods and the aforesaid symbols and characters, as the sacred scribe Chaeremon says."

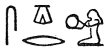

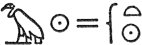

Accuracy of Tzetzes' statements proved.1. "And for joy, they would depict a woman beating a tambourine."

seḳer, "to beat a tambourine," and

seḳer, "to beat a tambourine," and

ṭechennu.]

ṭechennu.]2. "For grief, a man clasping his chin in his hand and bending towards the ground."

is the determinative of the word

is the determinative of the word

chaȧnȧu, "grief." A seated woman with head bent and hands thrown up before her face, is the determinative of

chaȧnȧu, "grief." A seated woman with head bent and hands thrown up before her face, is the determinative of

ḥath, "to weep."]

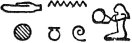

ḥath, "to weep."]3. "For misfortune, an eye weeping."

is the determinative of the common word

is the determinative of the common word

rem," to weep."]

rem," to weep."]4, "For want, two hands stretched out empty."

, ȧt, "not to have," "to be without." Coptic

, ȧt, "not to have," "to be without." Coptic

.]

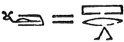

.]5. "For rising, a snake coming out of a hole."

per," to come forth, to rise" (of the sun) ]

per," to come forth, to rise" (of the sun) ]6. "For setting, [the same] going in."

āq, "to enter, to set" (of the sun).]

āq, "to enter, to set" (of the sun).]7. "For vivification, a frog." 1

, ḥefennu, means 100,000, hence fertility and abundance of life.]

, ḥefennu, means 100,000, hence fertility and abundance of life.]

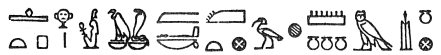

Accuracy of Tzetzes' statements proved.8. "For soul, a hawk; and also for sun and god."

ba, "soul,"

ba, "soul,"

neter, "god," and

neter, "god," and

Ḥeru, "Horus" or "the Sun-god."]

Ḥeru, "Horus" or "the Sun-god."]9. "For a female-bearing woman, and mother and time and sky, a vulture."

mut, "mother," is the common meaning of a vulture, and at times the goddess Mut seems to be identified with

mut, "mother," is the common meaning of a vulture, and at times the goddess Mut seems to be identified with

nut, "the sky." Horapollo says that the vulture also meant "year" (ed. Leemans, p. 5), and this statement is borne out by the evidence of the hieroglyphics, where we find that

nut, "the sky." Horapollo says that the vulture also meant "year" (ed. Leemans, p. 5), and this statement is borne out by the evidence of the hieroglyphics, where we find that

renpit, "year."]

renpit, "year."]10. "For king, a bee."

suten net, "king of the North and South."]

suten net, "king of the North and South."]11. "For birth and natural growth, and males, a beetle."

xeperȧ was the emblem of the god Cheperȧ

xeperȧ was the emblem of the god Cheperȧ

, who is supposed to have created or evolved himself, and to have given birth to gods, men, and every creature and thing in earth and sky. The word

, who is supposed to have created or evolved himself, and to have given birth to gods, men, and every creature and thing in earth and sky. The word

means "to become," and in late texts

means "to become," and in late texts

cheperu may be fairly well rendered by "evolutions." The meaning male comes, of course, from the idea of the ancients that the beetle had no female. See infra, under Scarab.]

cheperu may be fairly well rendered by "evolutions." The meaning male comes, of course, from the idea of the ancients that the beetle had no female. See infra, under Scarab.]12. "For earth, an ox."

ȧḥet means field, and

ȧḥet means field, and

ȧḥ means "ox"; can Chaeremon have confused the meanings of these two words, similar in sound?]

ȧḥ means "ox"; can Chaeremon have confused the meanings of these two words, similar in sound?]13. "And the fore part of a lion signifies dominion and protection of every kind."

Accuracy of Tzetzes' statements proved.

ḥā, "chief, that which is in front, duke, prince."]

ḥā, "chief, that which is in front, duke, prince."]14. "A lion's tail, necessity."

peḥ, "to force, to compel, to be strong."]

peḥ, "to force, to compel, to be strong."]15, 16. "A stag, year; likewise the palm."

or

or

renpit, is the common word for "year."]

renpit, is the common word for "year."]17. "The boy signifies growth."

which is the determinative of words meaning "youth" and juvenescence.]

which is the determinative of words meaning "youth" and juvenescence.]18. "The old man, decay."

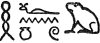

, the determinative of

, the determinative of

ȧan, "old age."]

ȧan, "old age."]19. "The bow, the swift power."

peṭ. Compare

peṭ. Compare

peṭ, "to run, to flee away."]

peṭ, "to run, to flee away."]"And others by the thousand. And by means of these characters Homer says this. But I will proceed in another place, if you please, to explain the pronunciation of those characters in Ethiopic fashion, as I have learnt it from Chaeremon." 1

Extract from Tzetzes.In another place 2 Tzetzes says, "Moreover, he was not uninitiated into the symbolic Ethiopian characters, the nature of which we will expound in the proper places. All this demonstrates that Homer was instructed in Egypt," ναὶ μὴν οὐδὲ τῶν Αἰθιοπικῶν συμβολικῶν γραμμάτων ἀμύητος γέγονε, περὶ ὧν ἐν τοῖς οἰκείοις τόποις διδάξομεν ὁποῖα εἰσι. καὶ ταῦτα δὲ τὸν Ὅμηρον ἐν Αἰγύπτῳ παιδευθῆναι παραδεικνύουσι and upon this the scholia on Tzetzes say:— Περὶ τῶν Αἰθιοπικῶν γραμμάτων Διό[δωρος] μὲν ἐπεμνήσθη, καὶ μερικῶς εἶπεν, ἀλλ᾽ ὥσπερ ἐξ ἀκοῆς ἄλλου μαθὼν καὶ οὐκ

ἀκριβῶς αὐτὸς ἐπιστάμενος [εἰ] καί τινα τούτων καέλεξεν ὥσπερ ἐν οἷς ὀ͂ιδε παῤῥησιάζεται. Χαιρήμων δὲ ὁ ἱερογραμματεὺς ὅλην βίβλον περὶ τῶν τοιούτων γραμμάτων συνέταξεν. ἅτινα, ἐν τοῖς τρο[σφόροις] τόποις τῶν Ὁμηρείων ἐπῶν ἀ[κρι]βέστερον καὶ πλατυτέρωσ ἐρῶ 1 "Diodorus made mention of the Ethiopian characters and spoke particularly, yet as though he had learnt by hearsay from another and did not understand them accurately himself, although he set down some of them, as though he were talking confidently on subjects that he knew. But Chaeremon the sacred scribe compiled a whole book about the aforesaid characters, which I will discuss more accurately and more fully in the proper places in the Homeric poems." It is much to be regretted that Chaeremon's work, if he ever fulfilled his promise, has not come down to us.

Greek translation of Egyptian text by Hermapion.One of the most valuable extracts from the works of Greek and Roman writers on Egypt is that from a translation of an Egyptian obelisk by Hermapion, preserved by Ammianus Marcellinus; 2 unfortunately, however, neither the name of Hermapion's work nor the time in which he lived is known. This extract consists of the Greek translation of six lines of hieroglyphics: three lines are from the south side of the obelisk, one line from the east side, and a second and a third line from the other sides. A comparison of the Greek extract with any inscription of Rameses II. on an obelisk shows at once that Hermapion must have had a certain accurate knowledge of hieroglyphics; his translation of the lines, however does not follow consecutively. The following examples will show that the Comparison of Greek translation with the Egyptian text.Greek, in many cases, represents the Egyptian very closely. Λέγει Ἥλιος βασιλεῖ Ῥαμέστῃ· δεδώρημαί σοι ἀνὰ πᾶσαν οἰκουμένην μετὰ χαρᾶς βασιλεύιν, ὃν Ἥλιος φιλεῖ =

"Says Rā, I give to thee all lands and foreign countries with rest of heart, O king of the north and south, Usr-maāt-Rā-setep-en-Rā,

son of the Sun, Rameses, beloved of Ȧmen-Rā." Θεογέννητος κτιστὴς τῆς οἰκουμένης =

"born the gods, possessor of the two lands" (i.e., the world). Ὁ ἑστὼς ἐπ᾽ ἀληθείας δεσπότης διαδήματος, τὴν Αἴγυπτον δοξάσας κεκτημένος, ὁ ἀγλαοποιήσας Ἡλίου πόλιν =

"born the gods, possessor of the two lands" (i.e., the world). Ὁ ἑστὼς ἐπ᾽ ἀληθείας δεσπότης διαδήματος, τὴν Αἴγυπτον δοξάσας κεκτημένος, ὁ ἀγλαοποιήσας Ἡλίου πόλιν =

"[the mighty bull], resting upon Law, lord of diadems, protector of Egypt, malting splendid Heliopolis with monuments." Ἥλιος θεὸς μέγας δεσπότης οὐραννοῦ =

"[the mighty bull], resting upon Law, lord of diadems, protector of Egypt, malting splendid Heliopolis with monuments." Ἥλιος θεὸς μέγας δεσπότης οὐραννοῦ =

"Says Rā Harmachis, the great god, lord of heaven," πληρώσας τὸν νεὼν τοῦ φοίνικος ἀγαθῶν, ᾧ οἱ θεοὶ ζωῆς χρόνον ἐδωρήσαντο =

"Says Rā Harmachis, the great god, lord of heaven," πληρώσας τὸν νεὼν τοῦ φοίνικος ἀγαθῶν, ᾧ οἱ θεοὶ ζωῆς χρόνον ἐδωρήσαντο =

"filling the temple of the bennu (phœnix) with his splendours, may the gods give to him life like the Sun for ever," etc.

"filling the temple of the bennu (phœnix) with his splendours, may the gods give to him life like the Sun for ever," etc.

Flaminian obelisk.The Flaminian obelisk, from which the Egyptian passages given above are taken, was brought from Heliopolis to Rome by Augustus, and placed in the Circus Maximus, 1 whence it was dug out; it now stands in the Piazza del Popolo at Rome, where it was set up by Pope Sixtus V. in 1589. 2 This obelisk was originally set up by Seti I., whose inscriptions occupy the middle column of the north, south, and west sides; the other columns of hieroglyphics record the names and titles of Rameses II. who, in this case, appropriated the obelisk of his father, just as he did that of Thothmes III. The obelisk was found broken into three pieces, and in order to render it capable of sustaining itself, three palms’ length was cut from the base. The texts have been published by Kircher, Oedipus Aegyptiacus, t. iii. p. 213; by Ungarelli, Interpretatio Obeliscorum Urbis, Rome, 1842, p. 65, sqq.,

plate 2; and by Bonomi, who drew them for a paper on this obelisk by the Rev. G. Tomlinson in Trans. Royal Soc. Lit., Vol. I. Second Series, p. 176 ff. For an account of this obelisk, see Zoëga, De Origine et Usu Obeliscorum, Rome, 1797, p. 92.

Champollion's estimate of Clement's statements on hieroglyphics.The next Greek writer whose statements on Egyptian hieroglyphics are of value is Clement of Alexandria, who flourished about AḌ. 191-220. According to Champollion, "un seul auteur grec, . . . . . . . . . a démêlé et signalé, dans l’écriture égyptienne sacrée, les élémens phonétiques, lesquels en sont, pour ainsi dire, le principe vital 1 . . . . . Clément d’Alexandrie s’est, lui seul, occasionnellement attaché à en donner une idée claire; et ce philosophe chrétien était, bien plus que tout autre, en position d’en être bien instruit. Lorsque mes recherches et l’étude constante des monuments égyptiens m’eurent conduit aux résultats précédemment exposés, je dus revenir sur ce passage de Saint Clément d’Alexandrie, que j’ai souvent cité, pour savoir si, à la faveur des notions que j’avais tirées d’un examen soutenu des inscriptions hiéroglyphiques, le texte de l’auteur grec ne deviendrait pas plus intelligible qu’il ne l’avait paru jusquelà. J’avoue que ses termes me semblèrent alors si positifs et si clairs, et les idées qu’il renferme si exactement conformes à ma théorie de l’écriture hiéroglyphique, que je dus craindre aussi de me livrer à une illusion et à un entraînement dont tout me commandait de me défier." 2 From the above it will be seen what a high value Champollion placed on the statements concerning the hieroglyphics by Clement, and they have, in consequence, formed the subject of various works by eminent authorities. In his Précis (p. 328), Champollion gives the extract from Clement with a Latin translation and remarks by Letronne. 3 Dulaurier in his Examen d’un passage des Stromates de Saint Clément d’Alexandrie, Paris, 1833, again published the passage and gave many explanations of words in it, and commented learnedly upon it. (See also

[paragraph continues] Bunsen's Aegyptens Stelle, Bd. I., p. 240, and Thierbach, Erklärung auf das Aegyptische Schriftwesen, Erfurt, 1846.) The passage is as follows 1:—

Clement of Alexandria on hieroglyphics.

Translation of extract from Clement."For example, those that are educated among the Egyptians first of all learn that system of Egyptian characters which is styled EPISTOLOGRAPHIC; secondly, the HIERATIC, which the sacred scribes employ; lastly and finally the HIEROGLYPHIC. The hieroglyphic sometimes speaks plainly by means of the letters of the alphabet, and sometimes uses symbols, and when it uses symbols, it sometimes (a) speaks plainly by imitation, and sometimes (b) describes in a figurative way, and sometimes (c) simply says one thing for another in accordance with certain secret rules. Thus (a) if they desire to write sun or moon, they make a circle or a crescent in plain imitation of the form. And when (b) they describe figuratively (by transfer and transposition without violating the natural meaning of words), they completely alter some things and make manifold changes in the form of others. Thus, they hand

down the praises of their kings in myths about the gods which they write up in relief. Let this be an example of the third form (c) in accordance with the secret rules. While they represent the stars generally by snakes’ bodies, because their course is crooked, they represent the sun by the body of a beetle, for the beetle moulds a ball from cattle dung and rolls it before him. And they say that this animal lives under ground for six months, and above ground for the other portion of the year, and that it deposits its seed in this globe and there engenders offspring, and that no female beetle exists."

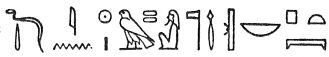

Three kinds of Egyptian writing.From the above we see that Clement rightly stated that the Egyptians had three kinds of writing:—epistolographic, hieratic and hieroglyphic. The epistolographic is that kind which is now called "demotic," and which in the early days of hieroglyphic decipherment was called "enchorial." The hieratic is the kind commonly found on papyri. The hieroglyphic kind is described as, I. cyriologic, that is to say, by means of figurative phonetic characters, e.g.,

emsuḥ, "crocodile," and II. symbolic, that is to say, by actual representations of objects, e.g.,

emsuḥ, "crocodile," and II. symbolic, that is to say, by actual representations of objects, e.g.,

"goose,"

"goose,"

"bee," and so on The symbolic division is subdivided into three parts: I. cyriologic by imitation, e.g.,

"bee," and so on The symbolic division is subdivided into three parts: I. cyriologic by imitation, e.g.,

, a vase with water flowing from it represented a "libation "; II. tropical, e.g.,

, a vase with water flowing from it represented a "libation "; II. tropical, e.g.,

, a crescent moon to represent "month,"

, a crescent moon to represent "month,"

, a reed and palette to represent "writing" or "scribe"; and III. enigmatic, e.g.,

, a reed and palette to represent "writing" or "scribe"; and III. enigmatic, e.g.,

, a beetle, to represent the "sun." 1 In modern Egyptian Grammars the matter is stated more simply, and we see that hieroglyphic signs are used in two ways: I. Ideographic, II. Phonetic.

, a beetle, to represent the "sun." 1 In modern Egyptian Grammars the matter is stated more simply, and we see that hieroglyphic signs are used in two ways: I. Ideographic, II. Phonetic.

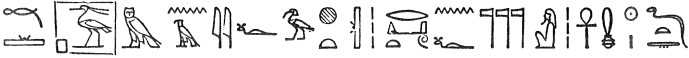

māu, "water," is an instance of the first method, and

māu, "water," is an instance of the first method, and

m-s-u-ḥ, is an instance of the second. Ideographic signs are used as determinatives, and are either ideographic or generic. Thus after

m-s-u-ḥ, is an instance of the second. Ideographic signs are used as determinatives, and are either ideographic or generic. Thus after

mȧu, "cat," a cat

mȧu, "cat," a cat

is placed, and is an ideographic determinative; but

is placed, and is an ideographic determinative; but

, heaven with a star in it, written after a

, heaven with a star in it, written after a

ḳerḥ, is a

ḳerḥ, is a

generic determinative. Phonetic signs are either Alphabetic as

a,

a,

b,

b,

k, or Syllabic, as

k, or Syllabic, as

men,

men,

chen, etc.

chen, etc.

Porphyry the Philosopher, who died about AḌ. 305, says of Pythagoras: 1—

Pythagoras and hieroglyphics."And in Egypt he lived with the priests and learnt their wisdom and the speech of the Egyptians and three sorts of writing, epistolographic and hieroglyphic and symbolic, which sometimes speak in the common way by imitation and sometimes describe one thing by another in accordance with certain secret rules." Here it seems that Porphyry copied Clement inaccurately. Thus he omits all mention of the Egyptian writing called "hieratic," and of the subdivision of hieroglyphic called "cyriologic," and of the second sub- division of the symbolic called "tropic." The following table, based on Letronne, will make the views about hieroglyphic writing held by the Greeks plain:— Letronne's summary.

112:1 See De rerum Aegyptiacarum scriptoribus Graecis ante Alexandrum Magnum, in Philologus, Bd. X. s. 525.

112:2 See the instances quoted in Philologus, Bd. X. s. 539.

112:3 Περὶ ἐν Μερόῃ ἱερῶν γραμμάτων. Diogenes Laertius, Vit. Democ., ed. Isaac Casaubon, 1593, p. 661.

112:4 Καὶ τὰ μὲν αὐτῶν ἱρὰ, τὰ δὲ δημοτικὰ καλὲεται. Herodotus, II. 36, ed. Didot, p. 84.

112:5 Diodorus, III. 4, ed. Didot, p. 129.

112:6 Strabo, XVII. I, § 46, ed. Didot, p. 693•

112:7 According to Mommsen he came to Rome, as tutor to Nero, in the reign of Claudius. Provinces of Rome, Vol. II. pp. 259, 273.

113:1 Γελώμενος δὲ τὸ πλέον ὡς ἀλαζὼν καὶ ἰδιώτησ. Strabo, XVII. 1, § 29, ed. Didot, p. 685.

113:2 Contra Apion., I. 32 ff. On the identity of Chaeremon the Stoic philosopher with Chaeremon the ἱερογραμματεὺς, see Zeller, Hermes, XI.

113:3 431. His other lost work, Αἰγυπτιακά, treated of the Exodus.

113:4 Praep. Evang., v. 10, ed. Gaisford, t. 1, p. 421.

113:5 Sub voce Ἱερογλυφικά.

113:6 For an account of them see Krumbacher, Geschichte aer Byzantinischen Literatur, München, 1891, pp. 235-242.

113:7 Ed. Kiessling, Leipzig, 1826, p. 191.

113:8 Draconis Stratonicensis Liber de Metris Poeticis. Joannis Tzetzae Exegesis in Homeri Iliadem. Primum edidit . . . God. Hermannus, Lipsiae, 1812.

115:1 But compare Horapollo, (ed. Leemans, p. 33), Ἄπλαστον δὲ ἄνθρωπον γράφοντες, βάτραχον ζωγραφοῦσιν.

117:1 Hermann, p. 123, ll. 2-29; Bachmann, p. 823, ll. 12-34.

117:2 Hermann, p. 17, ll. 21-25; Bachmann, p. 755, ll. 9-12.

118:1 Hermann, p. 146, ll. 12-22; Bachmann, p. 838, ll. 31-37.

118:2 Liber XVII. 4.

119:1 Qui autem notarum textus obelisco incisus est veteri, quem videmus in Circo etc. Ammianus Marcellinus, XVII. 4, § 17. It seems to be referred to in Pliny, XXXVI. 29.

119:2 For a comparative table of obelisks standing in 1840, see Bonomi, Notes on Obelisks, in Trans. Royal Soc. Lit., Vol. I. Second Series, p. 158.

120:1 Précis du Système hiéroglyphique des anciens Egyptiens, Paris, 1824, p. 321.

120:2 Précis, p. 327.

120:3 See also Œuvres Choisies, t. I. pp. 237-254.

121:1 Clem. Alex., ed. Dindorf, t. III. Strom. lib. V. §§ 20, 21, pp. 17, 18.

122:1 Champollion, Précis, p. 278.

123:1 Porphyry, De Vita Pythagorae, cd. Didot, § 11, p. 89, at the foot.