Sacred Texts Native American Maya Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

Yucatan Before and After the Conquest, by Diego de Landa, tr. William Gates, [1937], at sacred-texts.com

Among the occupations of the Indians were pottery and wood-working; they made much profit from forming idols of clay and wood, in doing which they fasted much and followed many rites. There were also physicians, or better named, sorcerers, who healed by use

|

Their favorite occupation was trading, whereby they brought in salt; also cloths

|

purses. In their markets they dealt in all the products of the country; they gave credit, borrowed and paid promptly and without usury.

The commonest occupation was agriculture, the raising of maize and the other seeds; these they kept in well-constructed places

|

|

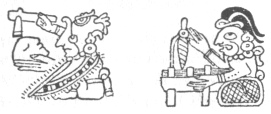

The growing plant springs from the head of the god Itzamna. The plant, springing from the earth, withers and is revived. The Corn deity holds forth the growing plant, springing from the sign ik, or Breath, Life. (All the figures shown on this page are from the Madrid Codex, which has chiefly to do with farm ceremonies.)

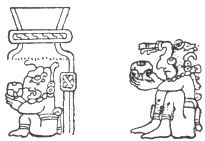

Itzamná plants the tree in the earth. Itzamná drops the seed in the earth and animals attack it. Worms attack the Corn-god, seated on the earth. Birds of prey feed on the dying Corn-god (note the closed eye).

with a stick, dropping in five or six grains, and covering them with the same stick. When it. rains, it is marvelous how they grow. In hunting also, they unite in bands of fifties, or more or less; the flesh of the deer they grill over rods to keep it from spoiling; then when they come back to the town they first make their presents to the chief and then distribute all as between friends. In fishing they do the same.

The Fire-dog, or heat rays from the sun, burns the growth, while the Corn-god, with arms bound, is dying. Next, Itzamná waters the growing maize, denoted by the kan-sign. The hunter ties up the deer.

In making visits the Indians always carry a gift, according to their quality, and the one visited returns the gifts with another. During these visits third persons present speak and listen attentively to those talking, having due regard for their rank; notwithstanding which all use the 'thou.' Those of less position must, however, in the course of the

|

For offenses committed by one against another the chief of the town required satisfaction to be made by the town of the aggressor; if this was refused it became the occasion of more trouble. If they were of the same town they laid it before the judge as arbitrator, and he ordered satisfaction given; if the offender lacked the means for this, his parents or friends helped him out. The cases in which they were accustomed to require such amends were in instances of involuntary homicide, the suicide of either husband or wife on the other's account, the accidental burning of houses, lands of inheritance, hives or granaries. Other offenses committed with malice called for reparation through blood or blows.

|