{Scanned at sacred-texts.com, November 2001}

{p. 105}

The Indian game of the ball play is common to all the tribes from Maine to California, and from the sunlit waters of the Gulf of Mexico to the frozen shores of Hudson bay. When or where the Indian first obtained the game it is not our province to inquire, but we may safely assume that the {Native American} shaped the pliant hickory staff with his knife and flint and twisted the net of bear sinew ages before visions of a western world began to float through the brain of the Italian dreamer.

In its general features, Indian ball play was the same all over the country, with this important exception, that among the northern and western tribes the player used but one ball stick, while in the Gulf States each contestant carried two and caught the ball between them. In California men and women played together, while among most of the more warlike tribes to the eastward it was pre-eminently a manly game, and it was. believed to insure defeat to a party if a woman even so much as touched a ball stick.

The game has a history, even though that history be fragmentary, like all that goes to make up the sum of our knowledge of the aboriginal race. The French, whose light-hearted gaiety and ready adaptability so endeared them to the hearts of their wild allies, were quick to take up the Indian ball game as a relief from the dreary monotony of long weeks in the garrison or lonely days in the forest. It became a favorite pastime, and still survives among the creoles of Louisiana under the name of Raquette, while in the more invigorating atmosphere of the North it assumed a new life, and, with the cruder features eliminated, became the famous Canadian national game of La Crosse. It was by means of a cleverly devised

{p. 106}

stratagem of a ball play that the ... warriors of Pontiac were enabled to surprise and capture the English garrison of old Fort Mackinaw in 11763. Two years before the Ojibwa chief had sent the ominous message: "Englishmen, although you have conquered the French, you have not yet conquered us;" but the warning was unheeded. The vengeance of the {Native American} may sleep, but never dies. On the fourth of June, 1763, the birthday of King George of England, the warriors of two great tribes assembled in front of the fort, ostensibly to play a game in honor of the occasion and to decide the tribal championship. The commandant himself came out to encourage his favorites and bet on the result, while the soldiers leaned against the palisades and the {women} sat about in groups, all intently watching every movement of the play. Suddenly there comes a crisis in the game. One athletic young fellow with a powerful stroke sends the ball high in air, and as it descends in a graceful curve it rolls along the ground to the gate of the fort, followed by four hundred yelling {Native Americans}. But look! As they run each painted warrior snatches from his {wife} the hatchet which she had concealed under her blanket, and the next moment it is buried in the brain of the nearest soldier. The English, taken completely by surprise, are cut down without resistance. ...

Let us turn from this dark picture to more recent times. In the late war three hundred of the East Cherokee entered the Confederate service and in the summer of 1863--just a century after the fatal day of Mackinaw--a detachment of them was left to guard the bridge over the Holston river, at Strawberry Plains, in Tennessee. But an Indian never takes kindly to anything in the nature of garrison duty, and time hung heavy on their hands. At last, in a moment of inspiration, one man proposed that they make some ball sticks and have a game. The suggestion was received with hearty favor, and soon all hands were at work putting up the poles, shaping the hickory sticks, and twisting the bark for the netting. The preliminary ceremonies were dispensed with for once, the players stripped, and the game began, while the rest of the Indians looked on with eager interest. Whether Wolf Town or the Big Cove would have

{p. 107}

won that game will never be known, for in the middle of it an advanced detachment of "the Yankees" slipped in, burned the bridge, and were moving forward, when the Cherokee, losing all interest in the game, broke for cover and left the Federals in possession of the ground.

In 1834, before the removal of the Cherokee to the west, a great game was played near the present site of Jasper, Georgia, between the settlements of Hickory Log and Coosawattee, in which there were eighteen players on a side, and the chiefs of the rival settlements wagered $1,000 apiece on the result.

There is a tradition among the few old traders still living in upper Georgia, to the effect that a large tract in this part of the state was won by the Cherokee from the Creeks in a ball play. There are no Cherokee now living in Georgia to substantiate the story, but I am inclined to put some faith in it from the fact that Coosawattee, although the name of a Cherokee settlement, signifies "the old country of the Creeks." The numerous localities in the Southern States bearing the name of "Ball Flat," "Ball Ground," and "Ball Play" bear witness to the fondness of the Indian for the play. To the red warrior it was indeed a royal game, worthy to be played on the king's day, with the empire of the northwest for the stake.

As speed and suppleness of limb and a considerable degree of muscular strength are prime requisites in the game, the players are always selected from among the most athletic young men, and to be known as an expert player was a distinction hardly less coveted than fame as a warrior. To bring the game to its highest perfection, the best players voluntarily subjected themselves to a regular course of training and conjuring; so that in time they came to be regarded as professionals who might be counted on to take part in every contest, exactly like the professional ball player among the whites. To farther incite them to strain every nerve for victory, two settlements, or sometimes two rival tribes, were always pitted against each other, and guns, blankets, horses--everything the Indian had or valued--were staked upon the result. The prayers and ceremonies of the shamans, the speeches of the old men, and the songs of the dancers were all alike calculated to stimulate to the highest pitch the courage and endurance of the contestants.

It is a matter of surprise that so little has been said of this game by travelers and other observers of Indian life, Powers, in his

{p. 108}

great work upon the California tribes, dismisses it in a brief paragraph; the notices in Schoolcraft's six bulky volumes altogether make hardly two pages, while even the artist Catlin, who spent years with the wild tribes, has but little to say of the game itself, although his spirited ball pictures go far to make amends for the deficiency. All these writers, however, appear to have confined their attention almost entirely to the play alone, noticing the ball-play dance only briefly, if at all, and seeming to be completely unaware of the secret ceremonies and incantations--the fasting, bathing, and other mystic rites--which for days and weeks precede the play and attend every step of the game; so that it may be said without exaggeration that a full exposition of the Indian ball play would furnish material for a fair sized volume. During several field seasons spent with the East Cherokee in North Carolina, the author devoted much attention to the study of the mythology and ceremonial of this game, which will now be described as it exists to-day among these Indians. For illustration, the last game witnessed on the reservation, in September, 1889, will be selected.

According to a Cherokee myth, the animals once challenged the birds to a great ball play. The wager was accepted, the preliminaries were arranged, and at last the contestants assembled at the appointed spot--the animals on the ground, while the birds took position in the tree-tops to await the throwing up of the ball. On the side of the animals were the bear, whose ponderous weight bore down all opposition; the deer, who excelled all others in running; and the terrapin, who was invulnerable to the stoutest blows. On the side of the birds were the eagle, the hawk, and the great Tlániwä--all noted for their swiftness and power of flight. While the latter were pruning their feathers and watching every motion of their adversaries below they noticed two small creatures, hardly larger than mice, climbing up the tree on which was perched the leader of the birds. Finally they reached the top and humbly asked the captain to be allowed to join in the game. The captain looked at them a moment and, seeing that they were four-footed, asked them why they did not go to the animals where they properly belonged. The little things explained that they had done so, but had been laughed at and rejected on account of their diminutive size. On hearing their story the bird captain was disposed to take pity on them, but there was one serious difficulty in the way-how could they join the birds when they had no wings? The eagle, the

{p. 109}

hawk, and the rest now crowded around, and after some discussion it was decided to try and make wings for the little fellows. But how to do it! All at once, by a happy inspiration, one bethought himself of the drum which was to be used in the dance. The head was made of ground-hog leather, and perhaps a corner could be cut off and utilized for wings. No sooner suggested than done. Two pieces of leather taken from the drum-head were cut into shape and attached to the legs of one of the small animals, and thus originated Tlameha, the bat. The ball was now tossed up, and the bat was told to catch it, and his expertness in. dodging and circling about, keeping the ball constantly in motion and never allowing it to fall to the ground, soon convinced the birds that they had gained a most valuable ally.

They next turned their attention to the other little creature, and now behold a worse difficulty! All their leather had been used in making the wings for the bat, and there was no time to send for more. In this dilemma it was suggested that perhaps wings might be made by stretching out the skin of the animal itself. So two large birds seized him from opposite sides with their strong bills, and by tugging and pulling at his fur for several minutes succeeded in stretching the skin between the fore and hind feet until at last the thing was done and there was Tewa, the flying squirrel. Then the bird captain, to try him, threw up the ball, when the flying squirrel, with a graceful bound, sprang off the limb and, catching it in his teeth, carried it through the air to another tree-top a hundred feet away.

When all was ready the game began, but at the very outset the flying squirrel caught the ball and carried it up a tree, then threw it to the birds, who kept it in the air for some time, when it dropped; but just before it reached the ground the bat seized it, and by his dodging and doubling kept it out of the way of even the swiftest of the animals until he finally threw it in at the goal, and thus won the victory for the birds. Because of their assistance on this occasion, the ball player invokes the aid of the bat and the flying squirrel and ties a small piece of the bat's wing to his ball stick or fastens it to the frame on which the sticks are hung during the dance.

The game, which of course has different names among the various tribes, is called anetsâ by the Cherokee. The ball season begins about the middle of summer and lasts until the weather

{p. 110}

is too cold to permit exposure of the naked body, for the players are always stripped for the game. The favorite time is in the fall, after the corn has ripened, for then the Indian has abundant leisure, and at this season a game takes place somewhere on the reservation at least every other week, while several parties are always in training. The training consists chiefly of regular athletic practice, the players of one side coming together with their ball sticks at some convenient spot of level bottom land, where they strip to the waist, divide into parties, and run, tumble, and toss the ball until the sun goes down. The Indian boys take to this sport as naturally as our youngsters take to playing soldier, and frequently in my evening walks I have come upon a group of little fellows from eight to twelve years old, all stripped like professionals, running, yelling, and tumbling over each other in their scramble for the ball, while their ball sticks clattered together at a great rate--altogether as noisy and happy a crowd of children as can be found anywhere in the world.

In addition to the athletic training, which begins two or three weeks before the regular game, each player is put under a strict gaktûnta, or tabu, during the same period. He must not eat the flesh of a rabbit (of which the Indians generally are very fond) because the rabbit is a timid animal, easily alarmed and liable to lose its wits when pursued by the hunter. Hence the ball player must abstain from it, lest he too should become disconcerted and lose courage in the game. He must also avoid the meat of the frog (another item on the Indian bill of fare) because the frog's bones are brittle and easily broken, and a player who should partake of the animal would expect to be crippled in the first inning. For a similar reason he abstains from eating the young of any bird or animal, and from touching an infant. He must not eat the fish called the hog-sucker, because it is sluggish in its movements. He must not eat the herb called atûnka or Lamb's Quarter (Chenopodium album), which the Indians use for greens, because its stalk is easily broken. Hot food and salt are also forbidden, as in the medical gaktûnta. The tabu always lasts for seven days preceding the game, but in most cases is enforced for twenty-eight days--i. e., 4 x 7--four and seven being sacred numbers. Above all, he must not touch a woman, and the player who should violate this regulation would expose himself to the summary vengeance of his fellows. This last tabu continues also for seven days after the game. As before stated, if a

{p. 111}

woman even so much as touches a ball stick on the eve of a game it is thereby rendered unfit for use. As the white man's law is now paramount, extreme measures are seldom resorted to, but in former days the punishment for an infraction of this regulation was severe, and in some tribes the penalty was death. Should a player's wife be with child, he is not allowed to take part in the game under any circumstances, as he is then believed to be heavy and sluggish in his movements, having lost just so much of his strength as has gone to the child. At frequent intervals during the training period the shaman takes the players to water and performs his mystic rites, as will be explained further on. They are also "scratched" on their naked bodies, as at the final game, but now the scratching is done in a haphazard fashion with a piece of bamboo brier having stout thorns which leave broad gashes on the backs of the victims.

When a player fears a particular contestant on the other side, as is frequently the case, his own shaman performs a special incantation, intended to compass the defeat and even the disabling or death of his rival. As the contending sides always belong to different settlements, each party makes all these preliminary arrangements without the knowledge of the other, and under the guidance of its own shamans, several of whom are employed on a side in every hotly contested game. Thus the ball play becomes as well a contest between rival shamans. Among primitive peoples the shaman is in truth all-powerful, and even so simple a matter as the ball game is not left to the free enjoyment of the people, but is so interwoven with priestly rites and influence that the shaman becomes the most important actor in the play.

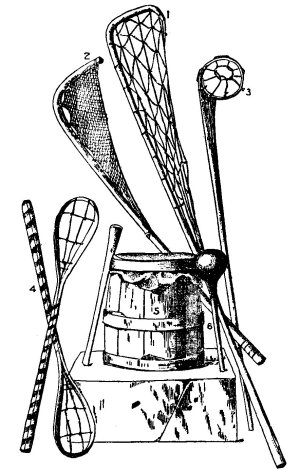

Before introducing the ball dance it is in place here to describe the principal implements of the game, the ball and ball stick. The ball now used is an ordinary leather-covered ball, but in former days it was made of deer hair and covered with deer skin. In California the ball is of wood. The ball sticks vary considerably among different tribes. As before stated, the Cherokee player uses a pair, catching the ball between them and throwing it in the same way.

The stick is something less than three feet in length and in its general appearance closely resembles a tennis racket, or a long wooden spoon, the bowl of which is a loose network of thongs of twisted squirrel skin or strings of Indian hemp. The frame is made of a slender hickory stick, bent upon itself and so trimmed and fashioned that the handle seems to be one solid round piece, when in fact it

{p. 112}

is double. The other southern tribes generally used sticks of the same pattern. Among the Sioux and Ojibwa of the north the player uses a single stick bent around at the end so as to form a hoop, in which a loose netting is fixed. The ball is caught up in this hoop and held there in running by waving the stick from side to side in

INSTRUMENTS OF THE GAME.

|

1 Iroquois. |

3. Ojibwa. |

5. Drum. |

|

2. Passamaquoddy. |

4. Cherokee. |

6. Rattle. |

a peculiarly dextrous manner. In the St. Lawrence region and Canada, the home of La Crosse, the stick is about four and a half feet long, and is bent over at the end like a shepherd's crook, with

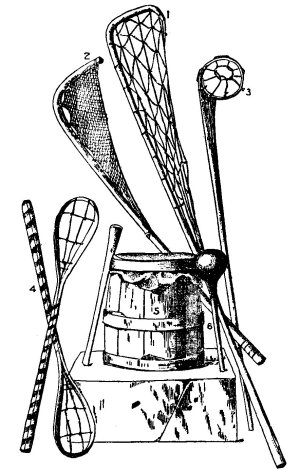

CHOCTAW BALL-PLAY DANCE IN 1832-FROM CATLIN.

{p. 114}

the netting extending half way down its length. The Passamaquoddy Indians of Maine use a stick with a strong, closely woven netting, which enables the stick to be used for batting. The sticks are ornamented with designs cut or burnt into the wood, and are sometimes further adorned with paint and feathers.

On the night preceding the game each party holds the ball-play dance in its own settlement. On the reservation the dance is always held on Friday night, so that the game may take place on Saturday afternoon, in order to give the players and spectators an opportunity to sleep off the effects on Sunday. It may be remarked here in parenthesis that the Cherokee word for Sunday signifies "when everybody does nothing all day long," showing that they fully appreciate its superior advantages as a day of rest. The dance must be held close to the river, to enable the players to "go to water" during the night, but the exact spot selected is always a matter of uncertainty, up to the last moment, excepting with a chosen few. If this were not the case a spy from the other settlement might endeavor to insure the defeat of the party by strewing along their trail a soup made of the hamstrings of rabbits, which would have the effect of rendering the players timorous and easily confused.

The dance begins soon after dark on the night preceding the game and lasts until daybreak, and from the time they eat supper before the dance until after the game, on the following afternoon, no food passes the lips of the players. On the occasion in question the young men of Yellow Hill were to contend against those of Raven Town, about ten miles further up the river, and as the latter place was a large settlement, noted for its adherence to the old traditions, a spirited game was expected. My headquarters were at Yellow Hill, and as the principal shaman of that party was my chief informant and lived in the same house with me, he kept me well posted in regard to all the preparations. Through his influence I was enabled to get a number of good photographic views pertaining to the game, as well as to observe all the shamanistic ceremonies, which he himself explained, together with the secret prayers recited during their performance. On a former occasion I attempted to take views of the game, but was prevented by the shamans, on the ground that such a proceeding would destroy the efficacy of their incantations.

Each party holds a dance in its own settlement, the game itself taking place about midway between. The Yellow Hill men were to have their dance up the river, about half a mile from my house.

{p. 115}

We started about 9 o'clock in the evening--for there was no need to hurry--and before long began to meet groups of dark figures by twos and threes going in the same direction or sitting by the roadside awaiting some lagging companions. It was too dark to distinguish faces, but familiar voices revealed the identity of the speakers, and among them were a number who had come from distances of six or eight miles. As we drew nearer, the measured beat of the Indian drum fell upon the ear, and soon we saw the figures of the dancers outlined against the firelight, while the soft voices of the women as they sang the chorus of the ball songs mingled their plaintive cadences with the shouts of the men.

The spot selected for the dance was a narrow strip of gravelly bottom, where the mountain came close down to the water's edge. The tract was only a few acres in extent and was covered with large trees, their tops bound together by a network of wild grape-vines which hung down on all sides in graceful festoons. From the road the ground sloped abruptly down to this bottom, while almost overhead the mountain was dimly outlined through the night fog, and close at hand one of the rapids, so frequent in these mountain streams, disturbed the stillness of the night with its never-ceasing roar.

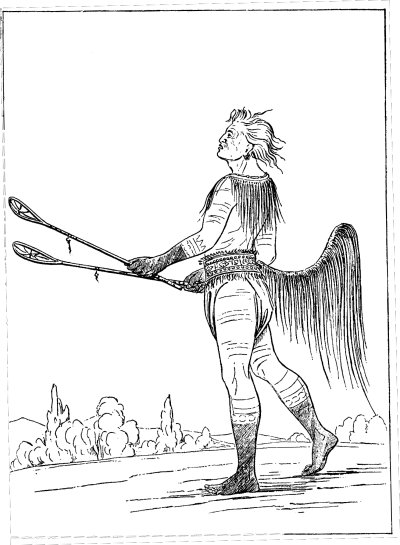

Several fires were burning and in the fitful blaze the trees sent out long shadows to melt into the surrounding darkness, while just within the circle of light, leaning against the trees or stretched out upon the ground, were the Indians, the women with their motionless figures muffled up in white sheets seeming like ghosts returned to earth, and the babies, whose mothers were in the dance, laid away under the bushes to sleep, with only a shawl between them and the cold ground. Around the larger fire were the dancers, the men stripped as for the game, with their ball-sticks in their hands and the firelight playing upon their naked bodies. It was a; weird, wild picture, not easily effaced from the memory.

The ball-play dance is participated in by both sexes, but differs considerably from any other of the dances of the tribe, being a dual affair throughout. The dancers are the players of the morrow, with seven women, representing the seven Cherokee clans. The men dance in a circle around the fire, chanting responses to the sound of a rattle carried by another performer, who circles around on the outside, while the women stand in line a few feet away and dance to and fro, now advancing a few steps toward the men, then wheeling and dancing away from them, but all the while

{p. 116}

keeping time to the sound of the drum and chanting the refrain to the ball songs sung by the drummer, who is seated on the ground on the side farthest from the fire. The rattle is a gourd fitted with a handle and filled with small pebbles, while the drum resembles a small keg with a head of ground-hog leather. The drum is partly filled with water, the head being also moistened to improve the tone, and is beaten with a single stick. Men and women dance separately throughout, the music, the evolutions, and the songs being entirely distinct, but all combining to produce an harmonious whole. The women are relieved at intervals by others who take their places, but the men dance in the same narrow circle the whole night long, excepting during the frequent halts for the purpose of going to water.

At one side of the fire are set up two forked poles, supporting a third laid horizontally, upon which the ball sticks are crossed in pairs until the dance begins. As already mentioned, small pieces from the wing of the bat are sometimes tied to these poles, and also to the rattle used in the dance, to insure success in the contest. The skins of several bats and swift-darting insectivorous birds were formerly wrapped up in a piece of deerskin, together with the cloth and beads used in the conjuring ceremonies later on, and hung from the frame during the dance. On finally dressing for the game at the ball ground the players took the feathers from these skins to fasten in their hair or upon their ball sticks to insure swiftness and accuracy in their movements. Sometimes also hairs from the whiskers of the bat are twisted into the netting of the ball sticks. The players are all stripped and painted, with feathers in their hair, just as they appear in the game. When all is ready an attendant takes down the ball sticks from the frame, throwing them over his arm in the same fashion, and, walking around the circle, gives to each man his own. Then the rattler, taking his instrument in his hand, begins to trot around on the outside of the circle, uttering a sharp Hï! to which the players respond with a quick Hi-hï'! while slowly moving around the circle with their ball sticks held tightly in front of their breasts, Then, with a quicker movement, the song changes to Ehu'! and the response to Hähï'!--Ehu'! Hähï'! Ehu'! Hähï'! Then, with a prolonged shake of the rattle, it changes again to Ahiye'! the dancers responding with the same word Ahiye'! but in a higher key; the movements become more lively and the chorus louder, till at a given signal with the rattle the players clap their

{p. 117}

ball sticks together, and facing around, go through the motions of picking up and tossing an imaginary ball. Finally with a grand rush they dance up close to the women, and the Hu-u'! part of the performance ends with a loud prolonged Hu-u'! from the whole crowd.

In the meantime the women have taken position in a line a few feet away, with their backs turned to the men, while in front of them the drummer is seated on the ground, but with his back turned toward them and the rest of the dancers. After a few preliminary taps on the drum he begins a slow, measured beat and strikes up one of the dance refrains, which the women take up in chorus. This is repeated a number of times until all are in harmony with the tune, when he begins to improvise, choosing words which will harmonize with the measure of the chorus and at the same time be appropriate to the subject of the dance. As this requires a ready wit in addition to ability as a singer, the selection of a drummer is a matter of considerable importance, and that functionary is held in corresponding estimation. He sings of the game on the morrow, of the fine things to be won by the men of his party, of the joy with which they will be received by their friends on their return from the field, and of the disappointment and defeat of their rivals. Throughout it all the women keep up the same minor refrain, like an instrumental accompaniment to vocal music. As Cherokee songs are always in the minor key, they have a plaintive effect, even when the sentiment is cheerful or even boisterous, and are calculated to excite the mirth of one who understands the language. This impression is heightened by the appearance of the dancers themselves, for the women shuffle solemnly back and forth all night long without ever a smile upon their faces, while the occasional laughter of the men seems half subdued, with none of the hearty ringing tones of the white man or the negro. The monotonous repetition, too, is something intolerable to any one but an Indian, the same words, to the same tune, being sometimes sung over and over again for a half hour or more. Although the singer improvises as he proceeds, many of the expressions have now become stereotyped and are used at almost every ball-play dance. The song here given is a good type of the class.

Through the kind assistance of Prof. John P. Sousa, director of the Marine band, I am enabled to give also the musical notation.

The words have no fixed order of arrangement and the song may be repeated indefinitely. Higanuyahi is the refrain sung by the

{p. 118}

women and has no meaning. The vowels have the Latin sound and û is the French nasal un:

FIRST SONG.

|

Hi'ganu'ya, |

hi'ganu'yahi' |

|

Hi'ganu'ya |

hi'ganu'yahi' |

|

Sâ'kwïli-te'ga |

tsï'tûkata'sûni'! |

|

As'taliti'ski |

tsï'tûkata'sûni'! |

|

As'taliti'ski |

tsa'kwakilû'testi'! |

|

U'watu'hi |

tsï'tûkata'sûni'! |

|

Tï'kanane'hi |

a'kwakilû'tati'! |

|

Uwa'tutsû'hi |

tsï'tûkata'sûni'! |

|

Uwa'tutsû'hi |

tsï'tûkata'sûni'! |

|

I'geski'yu |

tsa'kwakilû'testi'! |

|

Tï'kanane'hi |

tsï'tûkata'sûni'!--Hu-û! |

Which may be freely rendered:

What a fine horse I shall win!

I shall win a pacer!

I shall be riding a pacer!

I'm going to win a pretty one!

A stallion for me to ride!

What a pretty one I shall win!

What a pretty one I shall ride!

How proud I'll feel when riding him!

I'm going, to win a stallion!--Hu-û!

{p. 119}

But sic transit gloria!--in these degenerate days the pacer is more likely to be represented by a cheap jack-knife. Another very pretty refrain is

SECOND SONG.

Yo'wida'nuwe' Yo'widanu'-da'nuwe'.

At a certain stage of the dance a man, specially selected for the purpose, leaves the group of spectators around the fire and retires a short distance into the darkness in the direction of the rival settlement. Then, standing with his face still turned in the same direction, he raises his hand to his mouth and utters four yells, the last prolonged into a peculiar quaver. He is answered by the players with a chorus of yells--or rather yelps, for the Indian yell resembles nothing else so much as the bark of a puppy. Then he comes running back until he passes the circle of dancers, when he halts and shouts out a single word, which may be translated, "They are already beaten!" Another chorus of yells greets this announcement. This man is called the Talala, or "woodpecker," on account of his peculiar yell, which is considered to resemble the sound made by a woodpecker tapping on a dead tree trunk. According to the orthodox Cherokee belief, this yell is heard by the rival players in the other settle men--who, it will be remembered, are having a ball dance of their own at the same time--and so terrifies them that they lose all heart for the game. The fact that both sides alike have a Talala in no way interferes with the theory.

At frequent intervals during the night all the players, accompanied by the shaman and his assistant, leave the dance and go down to a retired spot at the river's bank, where they perform the mystic rite known as "going to water," hereafter to be described. While the players are performing this ceremony the women, with the drummer, continue the dance and chorus. The dance is kept up without intermission, and almost without change, until daybreak. At the final dance green pine tops are thrown upon the fire, so as to produce a thick smoke, which envelops the dancers. Some

{p. 120}

mystic properties are ascribed to this pine smoke, but what they are I have not yet learned, although the ceremony seems to be intended as an exorcism, the same thing being done at other dances when there has recently been a death in the settlement.

At sunrise the players, dressed now in their ordinary clothes, but carrying their ball sticks in their hands, start for the ball ground, accompanied by the shamans and their assistants. The place selected for the game, being always about midway between the two rival settlements, was in this case several miles above the dance ground and on the opposite side of the river. On the march each party makes four several halts, when each player again "goes to water" separately with the shaman. This occupies considerable time, so that it is usually after noon before the two parties meet on the ball ground. While the shaman is busy with his mysteries in the laurel bushes down by the water's edge, the other players, sitting by the side of the trail, spend the time twisting extra strings for their ball sticks, adjusting their feather ornaments and discussing the coming game. In former times the player during these halts was not allowed. to sit upon a log, a stone, or anything but the ground itself; neither was it permissible to lean against anything excepting the back of another player, on penalty of defeat in the game, with the additional risk of being bitten by a rattlesnake. This rule is now disregarded, and it is doubtful if any but the older men are aware that it ever existed.

On coming up from the water after the fourth halt the principal shaman assembles the players around him and delivers an animated harangue, exhorting them to do their utmost in the coming contest, telling them that they will undoubtedly be victorious as the omens are all favorable, picturing to their delighted vision the stakes to be won and the ovation awaiting them from their friends after the game, and finally assuring them in the mystic terms of the formulas that their adversaries Will be driven through the four gaps into the gloomy shadows of the Darkening Land, where they will perish forever from remembrance. The address, delivered in rapid, jerky tones like the speech of an auctioneer, has a very inspiriting effect upon the hearers and is frequently interrupted by a burst of exultant yells from the players. At the end, with another chorus of yells, they again take up the march.

On arriving in sight of the ball ground the Talala again comes to the front and announces their approach with four loud yells,

{p. 121}

ending with a long quaver, as on the previous night at the dance. The players respond with another yell, and then turn off to a convenient sheltered place by the river to make the final preparations.

The shaman then marks off a small space upon the ground to represent the ball field, and, taking in his hand a small bundle of sharpened stakes about a foot in length, addresses each man in turn, telling him the position which he is to occupy in the field at the tossing up of the ball after the first inning, and driving down a stake to represent each player until he has a diagram of the whole field spread out upon the ground.

The players then strip for the ordeal of scratching. This painful operation is performed by an assistant, in this case by an old man named Standing Water. The instrument of torture is called a kanuga and resembles a short comb with seven teeth, seven being also a sacred number with the Cherokees. The teeth are made of sharpened splinters from the leg bone of a turkey and are fixed in a frame made from the shaft of a turkey quill, in such a manner that by a slight pressure of the thumb they can be pushed out to the length of a small tack. Why the bone and feather of the turkey should be selected I have not yet learned, but there is undoubtedly an Indian reason for the choice.

The players having stripped, the operator begins by seizing the arm of a player with one hand while holding the kanuga in the other, and plunges the teeth into the flesh at the shoulder, bringing the instrument down with a steady pressure to the elbow, leaving seven white lines which become red a moment later, as the blood starts to the surface. He now plunges the kanaga in again at another place near the shoulder, and again brings it down to the elbow. Again and again the operation is repeated until the victim's arm is scratched in twenty-eight lines above the elbow. It will be noticed that twenty-eight is a combination of four and seven, the two sacred numbers of the Cherokees. The operator then makes the same number of scratches in the same manner on the arm below the elbow. Next the other arm is treated in the same way; then each leg, both above and below the knee, and finally an X is scratched across the breast of the sufferer, the upper ends are joined by another stroke from shoulder to shoulder, and a similar pattern is scratched upon his back. By this time the blood is trickling in little streams from nearly three hundred gashes. None of the scratches are deep, but they are unquestionably very painful, as all

{p. 122}

agree who have undergone the operation. Nevertheless the young men endure the ordeal willingly and almost cheerfully, regarding it as a necessary part of the ritual to secure success in the game. In order to secure a picture of one young fellow under the operation I stood with my camera so near that I could distinctly hear the teeth tear through the flesh at every scratch with a rasping sound that sent a shudder through me, yet he never flinched, although several times he shivered with cold, as the chill autumn wind blew upon his naked body. This scratching is common in Cherokee medical practice, and is variously performed with a brier, a rattlesnake's tooth, a flint, or even a piece of broken glass. It was noted by Adair as early as 1775. To cause the blood to flow more freely the young men sometimes scrape it off with chips as it oozes out. The shaman then gives to each player a small piece of root, to which he has imparted magic properties by the recital of certain secret formulas. Various roots are used, according to the whim of the shaman, their virtue depending entirely upon the ceremony of consecration. The men chew these roots and spit out the juice over their limbs and bodies, rubbing it well into the scratches, then going down to the water plunge in and wash off the blood, after which they come out and dress themselves for the game.

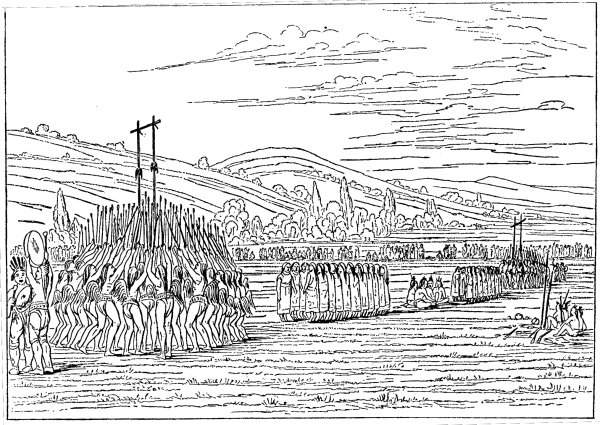

The modern Cherokee ball costume consists simply of a pair of short trunks ornamented with various patterns in red or blue cloth, and a feather charm worn upon the head. Formerly the breechcloth alone was worn, as is still the case in some instances, and the strings with which it was tied were purposely made weak, so that if seized by an opponent in the scuffle the strings would break, leaving the owner to escape with the loss of his sole article of raiment. This calls to mind a similar custom among the ancient Greek athletes, the recollection of which has been preserved in the etymology of the word gymnast. The ornament worn in the hair is made up of an eagle's feathers, to give keenness of sight; a deer tail, to give swiftness; and a snake's rattle, to render the wearer terrible to his adversaries. If an eagle's feathers cannot be procured, those of a hawk or any other swift bird of prey are used. In running, the snake rattle is made to furnish a very good imitation of the sound made by the rattlesnake when about to strike. The player also marks his body in various patterns with paint or charcoal. The charcoal is taken from the dance fire, and whenever possible is procured by burning the wood of a tree which has been struck by

{p. 123}

CHOCTAW BALL PLAYER IN 1832-FROM CATLIN.

{p. 124}

lightning, such wood being regarded as peculiarly sacred and endowed with mysterious properties. According to one formula, the player makes a cross over his heart and a spot upon each shoulder, using pulverized charcoal procured from the shaman and made by burning together the wood of a honey-locust tree and of a tree which has been struck by lightning, but not killed. The charcoal is pulverized and put, together with a red and a black bead, into an empty cocoon from which one end has been cut off. This paint preparation makes the player swift like the lightning and invulnerable as the tree that defies the thunderbolt, and renders his flesh as hard and firm to the touch as the wood of the honey-locust. Among the Choctaws, according to Catlin, a tail of horse hair was also worn, so as to stream out behind as the player ran. Just before dressing, the players rub their bodies with grease or the chewed bark of the slippery elm or the sassafras, until their skin is slippery as that of the proverbial eel.

A number of precautionary measures are also frequently resorted to by the more prudent players while training in order to make assurance doubly sure. They bathe their limbs with a decoction of the Tephrosia Virginiana or Catgut in order to render their muscles tough like the roots of that plant. They bathe themselves with a decoction of the small rush (Juncus tenuis) which grows by the roadside, because its stalks are always erect and will not lie flat upon the ground, however much they may be stamped and trodden upon. In the same way they bathe with a decoction of the wild crabapple or the ironwood, because the trunks of these trees, even when thrown down, are supported and kept up from the ground by their spreading tops. To make themselves more supple they whip themselves with the tough stalks of the Wä'takû or Stargrass or with switches made from the bark of a hickory sapling which has grown up from under a log that has fallen across it, the bark being taken from the bend thus produced in the sapling. After the first scratching the player renders himself an object of terror to his opponents by eating a portion of a rattlesnake which has been killed and cooked by the shaman. He rubs himself with an eel skin to make himself slippery like the eel, and rubs each limb down once with the fore and hind leg of a turtle because the legs of that animal are remarkably stout. He applies to the shaman to conjure a dangerous opponent, so that he may be unable to see the ball in its flight, or may dislocate a wrist or break a leg. Sometimes the shaman draws upon the ground

{p. 125}

an armless figure of his rival, with a hole where his heart should be. Into this hole he drops two black beads, covers them with earth and stamps upon them, and thus the dreaded rival is doomed, unless (and this is always the saving clause) his own shaman has taken precautions against such a result, or the one in whose behalf the charm is made has rendered the incantation unavailing by a violation of some one of the interminable rules of the gaktunta.

The players having dressed are now ready to "go to water" for the last time, for which purpose the shaman selects a bend of the river where he can look toward the east while facing up-stream. This ceremony of going to water is the most sacred and impressive in the whole Cherokee ritual, and must always be performed fasting, and in most cases also is preceded by an all-night vigil. It is used in connection with prayers to obtain a long life, to destroy an enemy, to win the love of a woman, to secure success in the hunt and the ball play, and for recovery from a dangerous illness, but is performed only as a final resort or when the occasion is one of special importance. The general ceremonial and the principal formulas are nearly the same in all cases. I have collected a number of the formulas used on these various occasions, but it is impossible within the limits of this paper to give more than a general idea of their nature.

The men stand side by side looking down upon the water, with their ball sticks clasped upon their breasts, while the shaman stands just behind them, and an assistant kneeling at his side spreads out upon the ground the cloth upon which are placed the sacred beads. These beads are of two colors, red and black, each kind resting upon a cloth of the same color, and corresponding in number to the number of players. The red beads represent the players for whom tile shaman performs the ceremony, while the black beads stand for their opponents, red being symbolic of power and triumph, while black is emblematic of death and misfortune. All being ready, the assistant hands to the shaman a red bead, which he takes between the thumb and finger of his right hand; and then a black bead, which he takes in the same manner in his left hand. Then, holding his hands outstretched, with his eyes intently fixed upon the beads, the shaman prays on behalf of his client to Yûwï Gûnahi'ta, the "Long Man," the sacred name for the river:

"O Long Man, I come to the edge of your body. You are mighty and most powerful. You bear up great logs and toss them

{p. 126}

about where the foam is white. Nothing can resist you. Grant me such strength in the contest that my enemy maybe of no weight in my hands--that I may be able to toss him into the air or dash him to the earth." In a similar strain he prays to the Red Bat in the Sun Land to make him expert in dodging; to the Red Deer to make him fleet of foot; to the great Red Hawk to render him keen of sight, and to the Red Rattlesnake to render him terrible to all who oppose him.

Then in the same low tone and broken accents in which all the formulas are recited the shaman declares that his client (mentioning his name and clan) has now ascended to the first heaven. As he continues praying he declares that he has now reached the second heaven (and here he slightly raises his hands); soon he ascends to the third heaven, and the hands of the shaman are raised still higher; then in the same way he ascends to the fourth, the fifth, and the sixth heaven, and finally, as he raises his trembling hands aloft, he declares that the spirit of the man has now risen to the seventh heaven, where his feet are resting upon the Red Seats, from which they shall never be displaced.

Turning now to his client the shaman, in a low voice, asks him the name of his most dreaded rival on the opposite side. The reply is given in a whisper, and the shaman, holding his hands outstretched as before, calls down the most withering curses upon the head of the doomed victim, mentioning him likewise by name and clan. He prays to the Black Fog to cover him so that he may be unable to see his way; to the Black Rattlesnake to envelop him in its slimy folds; and at last to the Black Spider to let down his black thread from above, wrap it about the soul of the victim and drag it from his body along the black trail to the Darkening Land in the west, there to bury it in the black coffin under the black clay, never to reappear. At the final imprecation he stoops and, making a hole in the soft earth with his finger (symbolic of stabbing the doomed man to the heart), drops the black bead into it and covers it from sight with a vicious stamp of his foot; then with a simultaneous movement each man dips his ball sticks into the water, and bringing them up, touches them to his lips; then stooping again he dips up the water in his hand and laves his head and breast.

Below is given a translation of one of these formulas, from the collection of original Cherokee manuscripts obtained by the writer. The formulistic name for the player signifies "admirer

{p. 127}

or lover of the ball play." The shaman directs his attention alternately to his clients and their opponents, looking by turns at the red or the black bead as he prays. He raises his friends to the seventh heaven and invokes in their behalf the aid of the bat and a number of birds, which, according to the Cherokee belief, are so keen of sight and so swift upon the wing as never to fail to seize their intended prey. The opposing players, on the other hand, are put under the earth and rendered like the terrapin, the turtle, the mole, and the bear--all slow and clumsy of movement. Blue is the color symbolic of defeat, red is typical of success, and white

signifies joy and happiness. The exultant whoop or shout of the players is believed to bear them on to victory, as trees are carried along by the resistless force of a torrent:

"THIS IS TO TAKE THEM TO WATER FOR THE BALL PLAY."

"Sgë! Now, where the white thread has been let down, quickly we are about to inquire into the fate of the lovers of the ball play.

They are of such a descent. They are called so and so. (As they march) they are shaking the road which shall never be joyful. The miserable terrapin has fastened himself upon them as they go about. They are doomed to failure. They have become entirely blue.

But now my lovers of the ball play have their roads lying down in this direction. The Red Bat has come and become one with them. There, in the first heaven, are the pleasing stakes. There, in the second heaven, are the pleasing stakes. The Peewee has come and joined them. Their ball sticks shall be borne along by the immortal whoop, never to fail them in the contest.

But as for the lovers of the ball play on the other side, the common turtle has fastened himself to them as they go about. There, under the earth, they are doomed to failure.

There, in the third heaven, are the pleasing stakes. The Red Tla'niwä has come and made himself one of them, never to be defeated. There, in the fourth heaven, are the pleasing stakes. The Crested Flycatcher has come and joined them, that they may never be defeated. There, in the fifth heaven, are the pleasing stakes. The Martin has come and joined them, that they may never be defeated.

The other lovers of the ball play--the Blue Mole has become one with them, that they may never feel triumphant. They are doomed to failure.

{p. 128}

There, in the sixth heaven, the Chimney Swift has become one with them, that they may never be defeated. There are the pleasing stakes. There, in the seventh heaven, the Dragonfly has become one of them, that they may never be defeated. There are the pleasing stakes.

As for the other lovers of the ball play, the Bear has come and fastened himself to them, that they may never be triumphant. He has caused the stakes to slip out of their hands and their share has dwindled to nothing. Their fate is forecast.

Sgë! Now let me know that the twelve (runs) are mine, O White Dragonfly. Let me know that their share is mine--that the stakes are mine. Now he [the rival player] is compelled to let go his hold upon the stakes. They [the shaman's clients] are become exultant and gratified. Yû!"

This ceremony ended, the players form in line, headed by the shaman, and march in single file to the ball ground, where they find awaiting them a crowd of spectators--men, women and children--sometimes to the number of several hundred, for the Indians always turn out to the ball play, no matter how great the distance, from old Big Witch, stooping under the weight of nearly a hundred years, down to babies slung at their mothers' backs. The ball ground is a level field by the river side, surrounded by the high timber-covered mountains. At either end are the goals, each consisting of a pair of upright poles, between which the ball must be driven to make a run, the side which first makes twelve home runs being declared the winner of the game and the stakes. The ball is furnished by the challengers, who sometimes try to select one so small that it will fall through the netting of the ball sticks of their adversaries; but as the others are on the lookout for this, the trick usually fails of its purpose. After the ball is once set in motion it must be picked up only with the ball sticks, although after having picked up the ball with the sticks the player frequently takes it in his hand and, throwing away the sticks, runs with it until intercepted by one of the other party, when he throws it, if he can, to one of his friends further on. Should a player pick up the ball with his hand, as sometimes happens in the scramble, there at once arises all over the field a chorus of Uwâ'yï Gûtï! Uwâ'yï Gûtï! "With the hand! With the hand!"--equivalent to our own Foul! Foul! and that inning is declared a draw.

{p. 129}

While our men are awaiting the arrival of the other party their friends crowd around them, and the women throw across their outstretched ball sticks the pieces of calico, the small squares of sheeting used as shawls, and the bright red handkerchiefs so dear to the heart of the Cherokee, which they intend to stake upon the game. It may be as well to state that these handkerchiefs take the place of hats, bonnets, and scarfs, the women throwing them over their heads in shawl fashion and the men twisting them like turbans about their hair, while both sexes alike fasten them about their throats or use them as bags for carrying small packages. Knives, trinkets, and sometimes small coins are also wagered. But these Cherokee to-day are poor indeed. Hardly a man among them owns a horse, and never again will a chief bet a thousand dollars upon his favorites, as was done in Georgia in 1834. To-day, however, as then, they will risk all they have.

Now a series of yells announces the near approach of the men from Raven Town, and in a few minutes they come filing out from the bushes-stripped,--scratched, and decorated like the others, carrying their ball sticks in their hands and headed by a shaman. The two parties come together in the center of the ground, and for a short time the scene resembles an auction, as men and women move about, holding up the articles they propose to wager on the game and bidding for stakes to be matched against them. The betting being ended, the opposing players draw Up in two lines facing each other, each man with his ball sticks laid together upon the ground in front of him, with the heads pointing toward the man facing him. This is for the purpose of matching the players so as to get the same number on each side; and should it be found that a player has no antagonist to face him, he must drop out of the game. Such a result frequently happens, as both parties strive to keep their arrangements secret up to the last moment. There is no fixed number on a side, the common quota being from nine to twelve. Catlin, indeed, speaking of the Choctaws, says that "it is no uncommon, occurrence for six or eight hundred or a thousand of these young men to engage in a game of ball, with five or six times that number of spectators;" but this was just after the removal, while the entire nation was yet camped upon the prairie in the Indian Territory. It would have been utterly impossible for the shamans to prepare a thousand players, or even one-fourth of that number, in the regular way, and in Catlin's spirited description of the game the ceremonial

{p. 130}

part is chiefly conspicuous by its absence. The greatest number that I ever heard of among the old Cherokee was twenty-two on a side. There is another secret formula to be recited by the initiated at this juncture, and addressed to the "Red Yahulu" or hickory, for the purpose of destroying the efficiency of his enemy's ball sticks.

During the whole time that the game is in progress the shaman, concealed in the bushes by the water side, is busy with his prayers and incantations for the success of his clients and the defeat of their rivals. Through his assistant, who acts as messenger, he is kept advised of the movements of the players by seven men, known as counselors, appointed to watch the game for that purpose. These seven counselors also have a general oversight of the conjuring and other proceedings at the ball-play dance. Every little incident is regarded as an omen, and the shaman governs himself accordingly.

An old man now advances with the ball, and standing at one end of the lines, delivers a final address to the players, telling them that Une'`lanû'hï, "the Apportioner"--the sun--is looking down upon them, urging them to acquit themselves in the game as their fathers have done before them; but above all to keep their tempers, so that none may have it to say that they got angry or quarreled, and that after it is over each one may return in peace along the white trail to rest in his white house. White in these formulas is symbolic of peace and happiness and all good things. He concludes with a loud "Ha! Taldu-gwü'! Now for the twelve!" and throws the ball into the air.

Instantly twenty pairs of ball sticks clatter together in the air, as their owners spring to catch the ball in its descent. In the scramble it usually happens that the ball falls to the ground, when it is picked up by one more active than the rest. Frequently, however, a man will succeed in catching it between his ball sticks as it falls, and, disengaging himself from the rest, starts to run with it to the goal; but before he has gone a dozen yards they are upon him, and the whole crowd goes down together, rolling and tumbling over each other in the dust, straining and tugging for possession of the ball, until one of the players manages to extricate himself from the struggling heap and starts off with the ball. At once the others spring to their feet and, throwing away their ball sticks, rush to intercept him or to prevent his capture, their black hair streaming out behind and their naked bodies glistening in the sun as they run. The scene is constantly changing. Now the players are all together

{p. 131}

at the lower end of the field, when suddenly, with a powerful throw, a player sends the ball high over the heads of the spectators and into the bushes beyond. Before there is time to realize it, here they come with a grand sweep and a burst of short, sharp Cherokee exclamations, charging right into the crowd, knocking men and women to right and left and stumbling over dogs and babies in their frantic efforts to get at the ball.

It is a very exciting game as well as a very rough one, and in its general features is a combination of base ball, {sic} football, and the old-fashioned shinny. Almost everything short of murder is allowable in the game, and both parties sometimes go into the contest with the deliberate purpose of crippling or otherwise disabling the best players on the opposing side. Serious accidents are common. In the last game which I witnessed one man was seized around the waist by a powerfully built adversary, raised up in the air and hurled down upon the ground with such force as to break his collar-bone. His friends pulled him out to one side and the game went on. Sometimes two men lie struggling on the ground, clutching at each other's throats, long after the ball has been carried to the other end of the field, until the "drivers," armed with long, stout switches, come running up and belabor both over their bare shoulders until they are forced to break their hold. It is also the duty of these drivers to gather the ball sticks thrown away in the excitement and restore them to their owners at the beginning of the next inning.

When the ball has been carried through the goal, the players come back to the center and take position in accordance with the previous instructions of their shamans. The two captains stand facing each other and the ball is then thrown up by the captain of the side which won the last inning. Then the struggle begins again, and so the game goes on until one party scores twelve runs and is declared the victor and the winner of the stakes.

As soon as the game is over, usually about sundown, the winning players immediately go to water again with their shamans and perform another ceremony for the purpose of turning aside the revengeful incantations of their defeated rivals. They then dress, and the crowd of hungry players, who have eaten nothing since they started for the dance the night before, make a combined attack on the provisions which the women now produce from their shawls and baskets. It should be mentioned that, to assuage thirst during the game, the players are allowed to drink a sour preparation made from green grapes and wild crabapples.

{p. 132}

Although the contestants on both sides are picked men and strive to win, straining every muscle to the utmost, the impression left upon my mind after witnessing a number of games is that the same number of athletic young white men would have infused more robust energy into the play--that is, provided they could stand upon their feet after all the preliminary fasting, bleeding, and loss of sleep. Before separating, the defeated party usually challenges the victors to a second contest, and in a few days preparations are actively under way for another game.

{p. 133}

Thus far the greater number of Ojibwa Indians of northern Minnesota have been slow to adopt the pursuits of their more civilized neighbors, preferring to spend their time in fishing and hunting and in gathering fruits and berries. In consequence of this mode of life the young men generally possess great endurance and are in excellent physical condition.

During the spring, summer, and autumn much of their time is spent in athletic sports, not so much for pleasure as for the desire to win the wagers of their opponents. The usual sports consist of horse racing, running, and ball play. To become a good ball player one must necessarily be possessed of speed and endurance.

Some of the local Indian runners have adopted an ingenious contrivance to aid in strengthening the muscles of the legs. While at their ordinary avocations, they wear about the ankles a thin bag of shot, sufficiently long to reach around the leg and admit of being tied over the instep. This is removed when occasion requires, and

they claim that they feel very light-footed. Two years ago one of the champion Ojibwa runners walked twenty-three miles after dinner, and next morning ran one hundred yards in ten and one-quarter seconds, easily beating his professional opponents.

The total number of Indians living in the vicinity of White Earth agency, Minnesota, is about two thousand, and it is easy to muster

{p. 134}

from eighty to one hundred ball players, who are divided into sides of equal number. If the condition of the ground permits, the two posts or goals are planted about one-third of a mile apart. Thus one stake only is used as a goal instead of two, as is the rule with the southern tribes. The best players of either side gather at the center of the ground. The poorer players arrange themselves around their respective goals, while the heaviest in weight scatter across the field between the starting point and the goals.

The ball is tossed into the air in the center of the field. As soon as it descends it is caught with the ball stick by one of the players, when he immediately sets out at full speed towards the opposite goal. If too closely pursued, or if intercepted by an opponent, he throws the ball in the direction of one of his own side, who takes up the race.

The usual method of depriving a player of the ball is to strike the handle of the ball stick so as to dislodge the ball; but this is frequently a difficult matter on account of a peculiar horizontal motion of the ball stick maintained by the runner. Frequently the

ball carrier is disabled by being struck across the arm or leg, thus compelling his retirement. Severe injuries occur only when playing for high stakes or when ill-feeling exists between some of the players.

Should the ball carrier of one side reach the opposite goal, it is necessary for him to throw the ball so that it touches the post. This is always a difficult matter, because, even if the ball be well directed, one of the numerous players surrounding the post as guards may intercept it and throw it back into the field. In this manner a single inning may be continued for an hour or more. The game may come to a close at the end of any inning by mutual agreement of the players, that side winning the greater number of scores being declared the victor.

The ball used in this game is made by wrapping thin strands of

{p. 135}

buckskin and covering the whole with a piece of the same. It is about the size of a base ball, though not so heavy.

The stick is of the same pattern as that used at the beginning of the present century by the Missisaugas, the Ojibwa of the eagle totem of the Province of Ontario. (See cut, p. 134.)

The game played by the Dakota Indians of the tipper Missouri was probably learned from the Ojibwa, as these two tribes have been upon amicable terms for many years; the ball sticks are identical in construction and the game is played in the same manner. Sometimes, however, the goals at either end of the ground consist of two heaps of blankets about twenty feet apart, between which the ball is passed.

When the Dakota play a game the village is equally divided into sides. A player offers as a wager some article of clothing, a robe, or a blanket, when an opponent lays down an object of equal value. This parcel is laid aside and the next two deposit their stakes, and so on until all have concluded. The game then begins, two of the three innings deciding the issue.

When the women play against the men, five of the women are matched against one of the latter. A mixed game of this kind is very amusing. The fact that among the Dakota women are allowed to participate in the game is considered excellent evidence that the game is a borrowed one. Among most other tribes women are not even allowed to touch a ball stick.

The players frequently hang to the belt the tail of a deer, antelope, or some other fleet animal, or the wings of swift-flying birds, with the idea that through these they are endowed with the swiftness of the animal. There are, however, no special preparations preceding a game, as feasting or fasting, dancing, etc.--additional evidence that the game is less regarded among this people.

The Chactas, Chickasaws, and allied tribes of Indian Territory frequently perform acts of conjuring in the ball field to invoke the assistance of their tutelary daimons. The games of these Indians are much more brutal than those of the northern tribes. The game sticks are longer, and made of hickory, and blows are frequently directed so as to disable a runner.