Sacred Texts Freemasonry Index Previous Next

Buy this Book on Kindle

Symbolical Masonry, by H.L. Haywood, [1923], at sacred-texts.com

"All great minds love the light," writes Brother J. F. Newton. "It is the mother of beauty and the joy of the world. It tells men all they know and their speech about it is gladsome and grateful. Light is to the mind what food is to the body; it brings the morning, when the shadows flee away, and the loveliness of earth is uncurtained. This is the mystery of light. It is not matter, but a form of motion; it is not spirit, though it seems closely akin to it; it is the gateway where matter and spirit pass and repass. Of all that is in nature it the most resembles God, in its gentleness, in its beauty, and in its pity."

This passage, so beautiful to read, and so revealing, would have met with a still more cordial response from the men of ancient days, for it seems that the first great religion of the world was the worship of light. As we read in Norman Lockyer's "Dawn of Astronomy": "Sunrise it was that inspired the first prayers of our race, and called forth the first sacrificial flames." After telling how large a place this light worship occupied among the remote peoples of India, the same author goes on to say, "The ancient Egyptians, whether they were separate from, or more or less allied in their origin to, the early inhabitants of India, had exactly the same view of Nature Worship, and we find in their hymns and in the lists of their gods that the Dawn and the Sunrise were the great

revelations of Nature, and the things which were most important to man; and therefore everything connected with the Sunrise and the Dawn was worshipped." Knowing little of the cure return of nature's cycles, the Egyptians were fearful lest, the sun having disappeared at dusk, he would forget to return; accordingly, the night was a season of foreboding and fear, while the Dawn was an occasion of rejoicing. Out of this alternation of fear and gladness, of the sun's apparent death, and his apparent return to life, arose that ancient Egyptian Light Religion, so many echoes of which remain with us in our Masonic symbolism.

The ritualism of light and darkness occurs and recurs throughout the Bible like a refrain. When Jehovah would bring the world out of the dripping chaos He is made to say, "Let there be Light"; of Him the Psalmist cried, "Thy word is a lamp unto my feet, and a light unto my path"; the Evangelist says of Him that "God is Light, and in Him is no darkness at all"; and the Book of Revelation promises the faithful that in the Great Life beyond, there will be no more night.

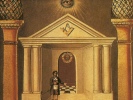

Jamblichus wrote that "Light is the simplicity, the penetration and the ubiquity of God." Zoroaster made light to stand for all the good of life, and darkness for its evil. In the Ancient Mysteries the candidate, clothed in white, went into the caverns of the night to issue thence into a place of illumination. The Kabbalist's great book was the "Zohar," which means light, and it is an exposition of the saying, "Let there be Light." Similarly one of the great mottoes of Masonry is "lux e tenebris," light out of darkness, while Masons, true Masons, are justly called the "sons of light"; and in all the ceremonies there is not

one more eloquent act than the "bringing of the candidate to light."

What is this Light that has been shed abroad in our lives? It is sometimes explained as Knowledge, and it is that; but it is more than that, for it is also Truth. Knowledge is the mind's awareness of a fact, while truth is the mind's understanding of the meaning of that fact. Facts may heap themselves up like the grains in a pile of sand; they may have little or no apparent relations with each other; and the man who is said to have knowledge of them may know little more than their number and their names. But when he has learned the hidden connections of these facts, how they bear upon each other, and what import they have for human life, he has learned Truth.

With this in mind, consider the world of men. Individuals jostle each other, they love and fight, events come and go, and the facts of life make and unmake themselves like summer clouds; thus considered the world is a jumble of unrelated happenings enough to bewilder the mind and freeze the heart. But Masonry says to this world, "Each and all of your facts are mystically bound together, your individuals are linked by unseen ties, and all your apparently warring forces are steadily at work to build a Temple in the world." Consider, also, the individual, himself. He finds in himself an array of feelings, thoughts, impulses, experiences, existing side by side, but apparently making for no end. To this man Masonry says, "The deepest forces in you are making toward Goodness, Beauty, Truth; far withdrawn in your nature is a Buried Temple; at the core of your being is the hidden Master; you are a potential Christ." When

[paragraph continues] Masonry utters this word, which is more than a word, to the world and to the man who lives in the world, it is revealing the hidden unity that binds the jangling facts together; it is finding the song among the strings; it is discovering the Lost Word; it is bringing truth, that is to say, Light, into the race of men; it says, "Let there be light, and there is light." To this end every symbol speaks; of this mission the Ritual is eloquent more than the tongues of men and of angels, from the first of it unto the last.