Sacred Texts Native American Maya Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

Yucatan Before and After the Conquest, by Diego de Landa, tr. William Gates, [1937], at sacred-texts.com

The first day of Popp, which is the first month of the Indians, was its New Year, a festival much celebrated among them, because it was general, and of all; thus the whole people together celebrated the festival for all their idols. To do this with the greater solemnity, on this day they renewed all the service things they used, as plates, vases, benches, mats and old garments, and the mantles around the idols. They swept their houses, and threw the sweepings and all these old utensils outside the city on the rubbish heap, where no one dared touch them, whatever his need.

For this festival the chiefs, the priest and the leading men, and those who wished to show their devoutness, began to fast and stay away from their wives for as long time before as seemed well to them. Thus some began three months before, some two, and others as they wished, but none for less than thirteen days. In these thirteen days then, to continence they added the further giving up of salt or pepper in their food; this was considered a grave penitential act among them. In this period they chose the chacs, the officials for helping the priest; on the small plaques which the priests had for the purpose, they prepared a great number of pellets of fresh incense for those in abstinence and fasting to burn to their idols. Those who began these fasts, did not dare to break them, for they believed it would bring evil upon them or their. houses.

When the New Year came, all the men gathered, alone, in the court of the temple, since none of the women were present at any of the temple ceremonies, except the old women who performed the dances. The women were admitted to the festivals held in other places. Here all clean and gay with their red-colored ointments, but cleansed of the black soot they put on while fasting, they came. When all were congregated, with the many presents of food and drink they had brought, and much wine they had made, the priest purified the temple, seated in pontifical garments in the

|

new fire and lit the brazier; because in the festivals celebrated by the whole community new fire was made wherewith to light the brazier. The priest began to throw in incense, and all came in their order, commencing with the chiefs, to receive incense from the hands of the priest, which he gave them with as much gravity as if he were giving them relics; then they threw it a little at a time into the brazier, waiting until it ceased to burn.

After this burning of the incense, all ate the gifts and presents, and the wine went about until they became very drunk. Such was the festival of the New Year, a ceremony very acceptable to their idols. Afterwards there were others who celebrated this festival, in this month Pop’, among their friends, and with the chiefs and the priests, these latter being always first in their banquets and drinking.

In the month Uo the priests, and the physicians and sorcerers (who were one) began, with fasting and the rest, to prepare to celebrate another festival. The hunters and fishermen began to celebrate on the 7th of Sip, each celebrating for himself on his own day. First the priests celebrated their fete, which was called Pocam ['the washing']; gathered in their regalia in the house of the chief, they first cast out the evil spirit as was their custom; after that they brought out their books and spread them upon the fresh leaves they had prepared to receive them. Then with many prayers and very devoutly they invoked an idol they called Kinch-ahau Itzamná, who

|

On the following day the physicians and sorcerers gathered in the house of one of them, with their wives. The priest exorcised the evil spirit. After that they opened the wrappings of their medicines, in which they had brought

|

|

After this each one wrapped up the implements of his office, and taking the pouch on his back all danced a dance they called Chantuniah. After the dance the men sat by themselves, and the women by themselves; and after putting

|

The next day the hunters gathered in the house of one of them, bringing their wives, like the others; the priests came and exorcised the evil spirit in their manner. Then they placed in the center the materials prepared for the sacrifice of the incense and the new fire, and the blue bitumen. Then with worship the hunters invoked the gods of the chase, Acanum, Suhuy-sib, Sipitabai, and others; they distributed the incense, which they then threw in the brazier; while it burned each one took an arrow and the skull of a deer, which the chacs anointed with the blue pitch; some then danced with these, as anointed, in their hands,

|

|

|

In the month Sotz the proprietors of the bee-hives prepared themselves to celebrate their festival in Tzec, and although the chief preparation here was fasting, there was no obligation save on the priest and the officers who assisted therein, and it was voluntary on the part of the rest.

|

In the twelfth chapter (Sec. VI) was related the departure of Kukulcán

from Yucatan, after which some of the Indians said he had departed to heaven with the gods, wherefore they regarded him as a god and appointed, a time when they should celebrate a festival for him as such; this the whole country did until the destruction of Mayapán. After that destruction

Click to enlarge INCENSE BURNER |

On the 16th of Xul all the chiefs and priests assembled at Maní, and with them a great multitude from the towns, all of them after preparing themselves by their fasts and abstinences. On the evening of that day they set out in a great procession, with many comedians, from the house of the chief where they had gathered, and marched slowly to the temple of Kukulcán, all duly decorated. On arriving, and offering their prayers, they set the banners on the top of the temple, and below in the court set each of them his idols on leaves of trees brought for this purpose; then making the new fire they began to burn their incense at many points, and to make offerings of viands cooked without salt or pepper, and drinks made from their beans and calabash seeds. There the chiefs and those who had fasted stayed for five days and nights, always burning copal and making their offerings, without returning to their homes, but continuing in prayers and certain sacred dances. Until the first day of Yaxkin these comedians frequented the principal houses, giving their plays and receiving the presents bestowed on them, and then taking all to the temple. Finally, when the five days were passed, they divided the gifts among the chiefs, priests and dancers, collected the banners and idols, returning them to the house of the chief, and thence each one to his home. They said and believed that Kukulcán descended on the last of those days from heaven and received their sacrifices, penances and offerings. This festival they called Chicc-kaban. *

In this month of Yaxkin they began to get ready, as usual, for the general festival they would celebrate in Mol, on the day appointed by the priest for all the gods; they called it Olob-sab-kamyax. After they were gathered in the temple and the same ceremonies and incense burning as in the previous festivals had been gone through with, they anointed with the blue pitch all the instruments of all the various occupations, from that of the priest to the spindles of the women, and even the posts of their houses. For this festival they assembled all the boys and girls, and in place of the painting and the ceremonies they gave to each nine little blows on the knuckles of their hands, outside; for the girls this was done by an old woman, vestured in a robe of feathers, who brought them there; from this she was called Ixmol, meaning the bringer together. These blows they gave them that they might grow up expert craftsmen in their fathers’ and mothers’ occupations. The conclusion was a fine drinking affair, with eating of the offerings, except that we must not believe that the devout old woman was allowed to become so drunk as to lose the feathers of her robe on the road.

In this month the bee-keepers held another festival like they did in the month Tzec, to the end that the gods might provide flowers for the bees.

One of the most arduous and difficult things these poor people had to do was the making of images of wood, which they called the gods. Thus they had a particular month designated for this work,

|

|

They worked in much reverence and fear, as they say, making the gods. When they were finished and the idols perfected, the owner made them the finest present he was able, of birds, game and their money, to pay for the labor of those who had made them. Then they removed them from the hut and set them in another enclosure of branches prepared for them in the court. where the priest blessed them with great solemnity, and an abundance of

devout prayers; but first the priest and the artisans removed the soot with which they had covered themselves during their fasting. Then having exorcised the evil one and burned the sanctified incense, they put the images wrapped n a cloth in a chest and delivered them to their owner, who very devotedly received them. Afterwards the good priest preached a little on the excellence of the artisans’ profession, or making new images of the gods, and on the ills that would have attended them had they not been faithful to the precepts of abstinence and fasting. After that they ate much and drank more.

In whichever of the months Ch’en or Yax were designated by the priest, and on the day set by him, they celebrated a festival they called Oc-na, meaning the 'renovation of the temple,' in honor of the Chacs, regarded as the gods of the maize fields. In this festival they consulted the predictions of the Bacabs, as we have told at more length in chapters 111 to 116 (Secs. XXXV to XXXVIII), and in conformity with the order there given. Each year they celebrated this festival and renewed the idols of terra cotta, and their braziers, since it was the custom for each idol to have his own little brazier for burning his incense; and if it was necessary they built a new house, or repaired the old one, placing on the wall the record of these things, with their characters.

A: January 29: 1 Imix. Here begins the calendar of the Indians, saying in their language, Hun Imix. *

|

f: February 17: 7 Ahau. On whatever day of the year 7 Ahau fell they celebrated a very great festival with incense and offerings, and restrained drinking; and since this was a movable feast it was in the care of the priests to publish it in sufficient time ahead, that they might fast in due manner.

On some one of the days of this month Mac the oldest people celebrated a festival to the Chacs, the gods of sustenance, and Itzamná. One or two days ahead of this they performed the following ceremony, which they called tupp-kak ('fire-quenching'). They hunted for as many animals and creatures

|

|

This was done in a different manner from the others, since for this they did not fast, except that the provider of the festival did his fast. When the time arrived, all the townsfolk, the priest and the officials assembled in the temple court, where they had a pyramid of stones, with stairways, all clean and dressed with green branches. The priest then gave the prepared incense to the one providing, and he burned it in the brazier, whereby they said the evil spirit was exorcised. This being done with their accustomed reverence, they spread the lower step of the pyramid with mud from the well, and the other steps with blue pitch.

They used much incense and invoked Itzamná and the Chacs with prayers and rituals, and made their offerings. When this had been done they took their comfort in eating and drinking what had been offered, confident that their service and invocations would bring a prosperous new year.

During the month Muan the owners of cacao plantations made a festival for the gods Ekchuah, Chac and Hobnil, who were their protectors. To do this they went to the property of one of them, where they sacrificed a dog spotted with the colors of the cacao, burned incense to their idols, and offered up iguanas of the blue sort, with certain bird's feathers, and other game; then they gave to each one of the officers a branch of the cacao fruit. After the sacrifice and the prayers they ate the gifts and drank, but (as they tell) no more than three draughts of the wine, no more than this having been brought. After this they went to the house of him who had provided the fiesta, for various diversions.

In this month of Pax they celebrated a festival called Pacum-chac, for which the priests and chiefs of the smaller villages gathered at the larger towns, where they all watched for five nights in the temple of Cit-chac-coh, with prayers, offerings and incense, as has been related of the festival to Kukulcán in the month Xul, in November. Before these days were passed, they all went to the house of their war general, the Nacon (of whom we spoke in chapter 101) (See. XXX), and with great pomp they conducted him to the temple, offering incense to him as to an idol, and then seating and incensing him as if he were a god; there he and they stayed through the five days, during which they ate and drank of the gifts that had been brought to the temple, and performed a great dance in the style of war manoeuvers, called in their language Holcan-okot, or the dance of the warriors. After these five days they went on to the fiesta which, since it was for matters of war and victory over their enemies, was very solemn.

First they went through the ceremony and sacrifices of the Fire, as I told under the month Mac; then in the usual manner they drove out the evil spirit with great solemnity. After this came prayers and the offering of gifts and incense, and while they were doing this the chiefs and those who had before assisted in this, again carried the Nacon on their shoulders around the temple, with incense. When they returned with him, the priests sacrificed a dog, drew out its heart and presented it between two platters to the demon, while the chacs each broke large jars full of liquor, and with this ended the festival. When it was over they ate and drank the gifts that had been brought, and then reconducted the Nacon to his home, with great ceremony, but without perfumes.

There they held a great fiesta in which the lords and the priests and leading men drank to intoxication, and the rest of the people went to their towns; but the Nacon did not join in the intoxication. On the next day, when the effects of the wine had passed off, all the lords and priests of the towns who had remained at the chief's house and taken part in this last act, received from him a great quantity of incense prepared for the purpose, which had been blessed by the holy priests. He then joined them and gave a long discourse in which with much emphasis he enjoined on them the festivals they should, in their own towns, celebrate for the gods, that the coming year might yield many things for their support. After the address, all departed with much expression of affection and noise, each going to his town and home.

There they busied themselves with the fiestas, which according to the circumstances, continued until the month Pop’, and which they called Sabacilthan, and performed as follows. They looked through the town for the richest men able to afford the costs of the fiesta, and set a day, to provide the most entertainment during the remaining three months before the new year. They gathered at the house of the feast maker, went through the ceremonies of driving away the evil spirit, burning copal, with offerings and dances, and making themselves such wine kegs, and such was the excess in these fiestas for these three months that it was painful to see them; for they went about scratched and bruised and red-eyed with the drink, all for this love of the wine for which they had destroyed themselves.

It has been told in the preceding chapters how the Indians began their year following these 'nameless days,' preparing there as with vigils for the celebration of the New Year festival; in the same interval they celebrated the festival of the Uvayeyab demon, for which they left their houses, which otherwise they left as little as possible; they offered besides gifts for the general festival, and counters for their gods and those of the temples. These counters they thus offered they never took for their own use, nor anything that was given to the god, but with them bought incense for burning. During these days

they neither combed nor washed, nor otherwise cared for themselves, neither men nor women; neither did they perform any servile or heavy work, fearing lest evil fall on them.

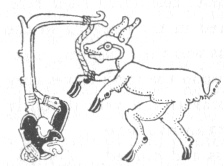

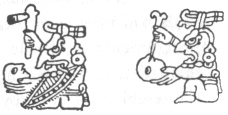

72:* The first two figures on this page are from the Dresden Codex, showing Ixchel as goddess p. 73 of medicine; of the rest, from the Madrid codex, in one the god Ekchuah traps the deer; next a vulture or kuch preys on the slain deer, and a hunter strikes a rattlesnake as it bites him; in the next a peccary, citám, is caught in a spring trap, and in the next an aspersarium, previously described, is being used in what is known as the 'chapter of the bees.' A little further on, under the month Xul, is shown one of the very handsome handled incense burners, of which a number of specimens have been found.

74:* We probably have here a survival from an earlier adjustment of the calendar, as shown both by the month-names and the ceremonies. Xul means 'end, termination,' and on the 16th they created new fire, and continued offerings and other ceremonies for the last five days of the month, paralleling those later carried on before the New Year beginning the 1st of Pop’. Kin means 'sun, day, time,' so that Yaxkin means 'new time.' And so even in the later changed arrangement they kept the month Yaxkin for the renewal of all utensils p. 75 with preparation for the very sacred ceremonial carving of the new images in the following month Mol, and carried through into Chen. In the accompanying figures, taken from the Madrid codex, the makers are ceremonially garbed in the habiliments of the gods, and are using what must have been the hardened copper tools elsewhere referred to by Landa, and such as have been actually recovered from the sacred cenote. Then in the months Ch’en or Yax followed the Oc-na ('house-entering' ceremony) or renovation of the temples, in honor of the gods of the fields.

In Landa's time the 16th of Xul fell on Nov. 8th, Yaxkin beginning Nov. 13th, and Mol ending just at the winter solstice, Dec. 22nd. Owing to our ignorance still as to just how the natural seasons and the months were kept adjusted without our quadrennial leap year method, we have not yet solved the question of the varying New Year dates found through all Middle America; but it is most interesting that this Xul-Yaxkin incidence should be tied in so closely with Quetzalcóatl, in whom we have the most tangled problem in the whole field. Nevertheless, while such specific seasonal ceremonies as planting, harvesting, hunting, etc., must somehow have been kept lined up to their regular month associations, still such a purely historical religious ceremony as this could remain fixed in the months once allotted, regardless of seasonal questions.

'What we can say with certainty is that, some thousand years before Landa wrote, the Mayas knew that 1507 true solar years of 365.2422 days equalled 1508 'vague' years of 361 days; so that New Year's or any other fixed date would keep falling behind not quite a quarter day every year, to come back in place again only after 1507 revolutions. So that we have here a case where clearly 'New Year' ceremonies were celebrated far out of their current place at Landa's time, and in a secondary 'survival' form, attached to the transitory presence of Quetzalcóatl in Yucatan (according to the traditions), while the greater and fuller sin-cleansing five-day ceremonies fell in July.

77:* The 'book of divination,' of lucky and unlucky days, called tzolkin, meaning 'day-count' in Maya, ch’olkih in Quiché, and tonalamatl in Aztec, was a period of 260 days, revolving continuously without regard to the calendar. It began with the day 1 Imix and ended with 13 Ahau, successively combining the thirteen numerals with the twenty day-names.